Read Part 1 >>

But let me now take you back to my earliest interactions with this remarkable woman.

* * *

On August 24, 1973, I conducted the first of my two interview sessions with Sue Kunitomi Embrey, who was then employed by UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center in a liaison capacity with Los Angeles’s large Japanese American population. This interview was the very first one of several hundred I would eventually transact as an oral historian, most of them with Japanese Americans and many with individuals connected with resistance activities.

During the drive to the interview site on the UCLA campus in Campbell Hall, I meditated on my two prior meetings the past spring with Embrey, a 50-year-old native daughter of Los Angeles who was my senior by sixteen years. Although I had telephoned her in January to confirm her participation in the March through June lecture series that I was coordinating at the University of California, Irvine, under the title of the “Japanese American Internment during World War II: A Socio-Historical Inquiry”—the first such event ever held—actual personal contact with Embrey was not made until two months before her June 5, 1973, presentation in the series.

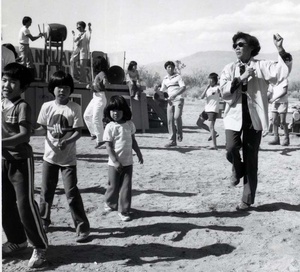

The day of our initial face-to-face encounter, April 14, 1973, marked the fourth annual Manzanar Pilgrimage. It was a particularly significant day both for Embrey and the Nikkei community. At the entrance to the onetime Manzanar War Relocation Center in Eastern California’s Owens Valley, Embrey, the chair and moving spirit of the Los Angeles-based Manzanar Committee, had presided over a dedication ceremony designating the site as a California state historical landmark.

First, a bronze plaque was cemented into a pagoda-style sentry house by Ryozo Kado, an octogenarian Issei master stone mason who, forty years earlier had constructed this structure. Thereafter, Embrey instructed the 1,000-1,500 “pilgrims”—a large throng of former internees and/or their offspring, a small contingent of government officials, and a sprinkling of interested spectators—to assemble inside the camp (proximate to where the December 6, 1942, Manzanar Riot had been staged) to hear commemorative addresses from Manzanar Committee representatives from America’s major metropolitan centers.

Notable among these representatives was Nisei Yuri Kochiyama, herself a Japanese American concentration camp survivor and a civil rights activist from New York who only eight years earlier, on February 21, 1965, had cradled her dying friend Malcolm X in her arms after he had been shot as he spoke at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. After Kochiyama and the other representatives had made their remarks, Embrey then directed the participants in the pilgrimage to gather around one of the ten raised placards bearing the place names of the War Relocation Authority detention centers and to weigh the words inscribed upon the bronze plaque.

In the early part of World War II, 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were interned in relocation centers by Executive Order 9066, issued on February 19, 1942.

Manzanar, the first of ten such concentration camps, was bounded by barbed wire and guard towers, confining 10,000 persons, the majority being American citizens.

May the injustices and humiliation suffered here as a result of hysteria, racism and economic exploitation never emerge again.

Because Embrey was preoccupied that day with coordinating the program and responding to media requests for interviews and background information, I was mostly able to observe her on this occasion as a public speaker.

In preparing myself for doing an array of interviews in the near future with Embrey and others, particularly Nisei, who were participants in and/or observers of the so-called "Manzanar Riot," I had been reading social-scientific literature pertaining to the interpersonal style of Nisei. The most comprehensive and telling piece I read in this connection was written by Stanford Lyman. He was a sociologist at the New School for Social Research in New York, who had been born in 1933 to immigrant eastern European Jewish parents and grew up during the Depression and pre-World War II period amid African Americans and Nisei in San Francisco’s “Western Addition” ghetto. After matriculating at Cal-Berkeley, he became the only non-Nikkei in a club comprised of recent Nisei returnees from the wartime camps. His assessment of the social and personal relations of Nisei, therefore, was rooted in protracted and intensive peer interaction.

The most germane section of Lyman’s scholarship for me was his delineation of how conversational discourse imprinted the Nisei personality. Not content with simply echoing the stereotypical observation made by many others about the omnipresence of etiquette in Nisei conduct, Lyman explained what he believed was the functional basis for this state of affairs—to conceal genuine feelings from others and to regularize behavior so as to avert unpleasant surprises—and even to emphasize the ways in which etiquette patterns the conversations among Nisei with non-Nisei.

Lyman suggested that etiquette is embedded in Nisei speech through tonal control, as evidenced by a pervasive flatness of tone and equality of conversational meter. Moreover, intimated Lyman, Nisei tonality frequently caused the uninitiated to doubt what was being said to them, and, further, to suspect that Nisei conversations often concealed ulterior motives. Additionally, Nisei had a penchant for lapsing into euphemistic language when touching upon topics considered unseemly or uncomfortable for those with whom they were talking. Also, Nisei regularly resorted to “abstract nouns, noncommittal statements and inferential hints at essential meanings, and typically did not come to grips right away with the gist of a given conversation.”

When non-Nisei asked Nisei pointed questions, Nisei responded with rhetorical management: refusing to answer, changing the subject, redirecting the conversation back to its concentric form, or burying potentially affective subjects beneath a verbal avalanche of trivia. Finally, observed Lyman, Nisei set their faces so as to achieve an expressionless countenance, thereby discouraging access by others to their inner selves.

So while I observed Sue Embrey discharging her public role that day at the Manzanar Pilgrimage, I was conscious of Lyman’s analysis of Nisei personal and social interactional style. To be sure, the customary Nisei attention to etiquette was firmly in place with Embrey, particularly in the deference she extended to politicians and the press.

But her impassioned address, which assailed American racism and imperialism and recounted the struggle the Manzanar Committee and its allies had waged against recalcitrant state bureaucrats to gain the controversial plaque wording, betrayed few of the telltale traits mentioned by Lyman. Embrey’s voice, facial expressions, and gestures were suitably varied to emphasize her unvarnished message. She gazed directly at the assembled crowd and spoke directly to us about unpleasant, and for some perhaps, unpalatable truths. Although comporting herself with decorum, her vigorous oratorical style implicitly mocked the title of Nisei Bill Hosokawa’s recent book about their common ethnic generation, Nisei: The Quiet Americans.

(Speaking parenthetically, I should point out here there that this implicit mocking became explicit in Richard Drinnon’s 1987 book Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism with the author’s reference to Sue Embrey as “an unquiet Nisei,” and again twenty years later, when Diana Bahr, appropriating Drinnon’s satirical designation, titled her 2007 oral historiographical biography of Sue Embrey The Unquiet Nisei.)

* This was a presentation at the Riverside Metropolitan Museum, in Riverside, California, on October 20, 2012, for a program to celebrate publication of Mark Howland Rawitsch’s 2012 book, The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream, published by the University Press of Colorado in the Lane Hirabayashi-edited NIKKEI IN THE AMERICAS series.

© 2012 Arthur A. Hansen