Read Part 9 >>

LABOR CONTRACTORS

Unlike Hawaii, where plantation workers had direct contract with their employers, on the Mainland, the Japanese workers often did not know who they worked for. Jobs were secured through labor contractors who acted as intermediaries between American employers and Japanese laborers. The contractors made enormous profits, extracting a daily commission from the workers’ wages with some providing commodities and services to the workers.

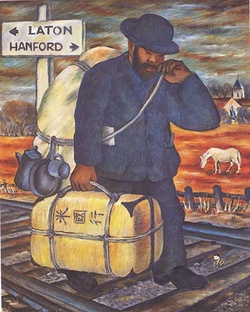

"To Find a Job" by Henry Sugimoto. 1950. Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa, Japanese American National Museum. (92.97.107)

There were more than 20 Japanese bosses who supplied Japanese workers for the railroads, lumber mills, farms, mines, and salmon canneries. Kyutaro Abiko, president of the Japan Labor Contractor Company, was the largest labor contractor or “boss” in San Francisco who supplied workers for the railroads, mines, and farms. Abiko, like most of the others who became contractors, had initially come to America to study in 1882. His ability to speak English and his knowledge of American labor practices enabled him to secure work for the laborers and to negotiate wages with the employer. His labor contracting enterprise would later help to subsidize his future endeavors.

The railroad labor contractors worked on the largest scale, sending workers to Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Oregon. Since railroad wages were relatively high ($1.00 to $1.25 for a 10 hour day’s work in 1903), this was the first job for many overseas workers. Toshiharu Kambe arrived in Seattle on October 8, 1907. Four days later he was working on a railroad construction in Bucoda, Washington. In his diary he wrote:

October 8, 1907: Entered United States of America on this day of October 8th, 1907 at Seattle Wash.

October 9: look around for a job.

October 10: Mr. Yoshino found a job.

October 11: No job yet. Letter to Japan.

October 12: got job railway construction at Bucoda.

October 13: Start from Seattle 10 a.m. arrived to Tacoma.

October 14: From Tacoma arrived Bucoda. Built camp here to stay.

October 15: first work in America today.

October 16: work well.

October 17: I worked very well.1

This entry was the last one written in Kambe’s diary; perhaps he was too exhausted, or felt too cramped and uncomfortable to write in the smoke-filled freight car that housed ten to fifteen workers.

Kambe and many other Issei left railroad work and moved to the city where the opportunities were greater. In Seattle he became the manager of The Pioneer Fruit Company and a prominent member of the Seattle Japanese community.

BURANKE KATSUGI (BLANKET CARRIERS) AND THE BACHELOR SOCIETY

Toyosaburo Sato landed in San Francisco on May 12, 1904. At the immigration station he heaved a sigh of relief when he passed the physical examination for trachoma, hookworms, tapeworms, and syphilis. Though he had passed a similar examination before boarding the ship, he knew if he failed the test in the United States, he would be sent back to Japan.

The immigration inspector had carefully checked Sato’s personal belongings., looking for letters of introduction or addresses of acquaintances in America. Discovery of such items could have cost Sato entry to American, particularly if the inspector suspected he was a contract laborer. But all he found in Sato’s wicker basket were his family registry (koseki tohon ), a school resume, his elementary, middle school, high school diplomas, and other personal effects.2

After passing his first major hurdle, twenty-one year old Toyosaburo felt optimistic about his future. Though he didn’t have a job already lined up, it was very likely he would find employment through private agents or labor recruiters. And if he made his way to a Japanese –owned inn, the innkeeper could have found him a job for a commission fee of two-dollars.

The information in the letters Sato received from 1929 until his death indicate that he was a buranke-katsugi, a migratory laborer who carried a blanket for bedding, using urban centers as a homebase while contracting for seasonal jobs in the outlying rural areas.3 A glimpse of his transient life is captured in the poem he wrote:

At evening dusk

I slip into bed without light.

Sleeping in the straw bed

The smell of straw lingers.4

The letters he received from relatives and friends read as follows:5

February 11, 1929: To T. Sato in Chico, California from Gyosuke Nagao in Tokyo (Nagao was a former roommate who had lived with Sato in America).

Your mother met Mr. And Mrs. Kusumi at the hot springs and had a good time. When the conversation turned to you, your mother said, “Toyosaburo, my son, is such an honest person—many people could take advantage of him. I wish he’d come home.” I urge you to return to Japan if you have enough money for passage. Your mother wants you to come home while she is still healthy. Take my word, I returned home after my parents had a stroke and they were unable to understand me. I don’t want the same to happen to you.November 18, 1929: To T. Sato in Chico from Saichi in Japan (Saichi is Sato’s eldest brother).

Mother died at night on August 19. She had a big funeral attended by many intellectuals. If you want to return to Japan, the sooner you come the better. You and Eijiro (the younger brother) could run the apple ranch.January 22, 1930: To T. Sato in Chico from Saichi Sato in Japan.

Come back to Japan any time. When you do, bring back knowledge of apple growing—this information will be very valuable since there are different ways of growing apples in America. Eijiro is now running a 1.5 hectares apple ranch....I bought 3.5 hectares for future cultivation. When you return, you can be in charge of the land....About a wife, we’ll talk about the arrangements in detail when a suitable person appears.January 17, 1931: To T. Sato in Oakland, California from G. Nagao in Tokyo.

I trust you are working hard and saving your money. I worry about your gambling and drinking habits. As I said in my last letter, bring back as much money as possible. Besides the boat fare, about $2,000 is necessary. Also, bring back new knowledge that can help you:

(1) How to grow asparagus.

(2) How to make apple cider

(3) How to make bacon, sausage, and hamSeptember 18. 1831: To T. Sato in Acampo from Reverend T. Hata in Oakland.

We heard you are back from Alaska....Everyone gathers here to write poetry. We all talk about you. Isso Shimoyama was very pleased that your article was published in the newspaper.March 17, 1932: To T. Sato in San Francisco forwarded to Bristol Bay, Alaska from Mr. Katai in Los Angeles (Mr. Katai is a fellow migrant laborer).

I want to go to Alaska too. Please send me a telegram in Los Angeles specifying the time of departure and date of return to San Francisco. I’d like to know the pay and how much I can receive in advance. Please discuss my request with bosses Nonoguchi and Sakamachi. I want to know right away.June 20,1932: To T. Sato in Alaska from Keizo Matsumori in Burlingame, California.

Please let me know when you return from Alaska. You bring the salmon and I’ll prepare the sake (rice wine).December 12, 1932: To T. Sato in Lodi, California from Roy Shima (aka) Fukushima in Palo Alto, California.

The great depression is now upon us. I tried to send money to you sooner but my pocket is empty—by the way, it always is. Enclosed is $20.00.January 5, 1933: Letter to T. Sato in Lodi from Fukushima in Palo Alto.

Happy New Year! Enclosed is $10.00. Sorry for the small amount I am sending to you but on December 4, Sunday, I tried to catch a canary that escaped from the cage and I fell from the roof top. I injured both legs and was confined to the bed under a doctor’s care.January 7, 1933: Letter to. T. Sato in Lodi from Nonoguchi, Alaskan labor contractor, in San Francisco:

I am sorry you are out of a job. I have enclosed a $5.00 check for you. There is no advance pay to Alaska. Please understand. The economy is bad.February 2, 1933: To T. Sato in Lodi from Shima in Palo Alto.

Sorry for the delay. Enclosed is $10.00. Please forgive me but I could not come up with more because of my injury. People do not loan money to a person like me, who used to frequent gambling dens.March 30, 1933: Letter to T. Sato in Stockton, c/o Diamond Hotel, from Shima in Palo Alto.

It must be very difficult for you since you are sick and with no money. People think that a person like me, who is working, can arrange money easily, but so many friends borrow money from me. At the time I’m helping a friend, from my same prefecture, whom I’ve known for more than 20 years....I’ll send you money as soon as I can.April 4, 1933: To Seito (Sato’s pen name) in Stockton from Yeitaro Shimoyama in San Francisco (Yeitaro Shimoyama was considered a genius by his literary peers. He was also known as Isso Shimoyama).

I sympathize with your situation in this period of economic depression. I myself have worked for the newspaper [Nichibei Shimbun ] for many days with no pay. Last week we did not receive any wages. After we threatened to strike, $2.50 was given to each of us. I am enclosing a leaf that I found—a symbol of victory. Perhaps as a result of these hard times and suffering, good poetry will flourish.April 5, 1933: Letter to T. Sato in Stockton, c/o Nippon Hotel, from Shima in Palo Alto.

Wishing you a speedy recovery.

Why Toyosaburo Sato came to America, we can only speculate. Perhaps he had come to study English or maybe to make money and return home—a little richer, a little wiser—to his distinguished family in Aomori prefecture. Whatever the reasons, he probably would have never guessed that the treasured belongings he had packed for his voyage, along with a packet of letters written by friends and family, would be among the only possessions to his name after twenty-nine years of hard work in the United States. On May 15, 1933, he passed away, destitute and alone, in French Camp, California.

My dreams of glory

Left home with me . . . but neither

They nor I returned

(Ryuka)6

Gambling was an important factor in preventing Sato and others like him from being able to save money and return to Japan. In June, 1918, a survey taken by the local Japanese association indicated that the Japanese immigrants were losing $3 million annually to the gambling houses. Sato probably staked his hopes and wages on a lucky score, mindful of his friend Nagao’s advice that “when you return to Japan you have to bring money with you....You should be able to live on the money you bring back.”

Gambling was also a source of recreation and companionship for many lonely young bachelors like Sato. Few women came in the early years of Japanese immigration to the U.S. Mainland. At the turn of the century there were 24 men for each woman.7 Among the earliest women who came to the mainland, quite a number were prostitutes. Some young girls were abducted or lured with false promises by unscrupulous agents; others were forced into prostitution or sold by impoverished rural families.8

After 1900 many men sent for their wives in Japan. Others returned to Japan to secure a bride. But for the bachelors who could not afford the trip back home, there were few available women to court and love affairs with other men’s wives sometimes developed. Husbands placed ads in the newspaper or posted announcements in the local Japanese association, offering rewards for the location of runaway wives. In the close-knit Japanese immigrant society few women could escape the scorn that an illicit love affair could bring.

Notes:

1. This diary is from the Kambe Family Collection of the Japanese American National Museum.

2. Toyosaburo Sato Collection, Courtesy of Issei Pioneer Museum, Salinas, California.

3. See Ben Kobashigawa (translator), History of the Okinawans in North America (Los Angeles, 1988), for the harvest migration cycle, pp. 327-328.

4. Letter written to Toyosaburo Sato from Reverend T. Hata, September 18, 1931, translated with the help of Yukiko Yoshida.

5. These letters were translated with the generous help of Reverend Yoshiaki Takemura from the Salinas Buddhist Church.

6. Ryuka, Kazuo Ito, Issei , p. 362.

7. In 1900, there was a ratio of four males to each female. More than 30 percent of the Japanese population was married.

8. See Yuji Ichioka, “Ameyuki-san: Japanese Prostitutes in Nineteenth Century America,” Amerasia Journal (Los Angeles, 1977).

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum