Read part 2 >>

Section 3: A Cross Cultural View: The View From People Between Countries

To me, the most confusing section of the exhibit was the one entitled “Foreign Correspondents in Occupied Japan,” although it also tried to express the theme of “people who were moving between countries” in the war era. Having no permission for residence in wartime, these correspondents were similar to Japanese in the U.S. at that time. However, the sudden change of the protagonists from “Japanese people” to “foreign correspondents” made me lose the thread of the exhibit. Probably this section intended to use their perspective to present how wartime Japan looked from a foreigner's perspective. But as the exhibit title included the term "Japanese Americans," indicating that the exhibit was about them, and the foreign correspondents were not all Japanese Americans, so it was hard to understand why these foreign residents in Japan were featured in the story.

Probably, the exhibit made an effort to show mutual characteristics between the two groups. For instance, like the immigrants, these foreign correspondents formed a society (correspondent’s society) in Japan. In addition to introducing the organization, the narrative presented the roles of foreign correspondents and their various lives in Japan, from the end of WWII to the Korean War (1945-1950). In order to send information out to the world from Japan under the occupation (1945-6) as witnesses, some correspondents abandoned their citizenship in their countries to stay in Japan.

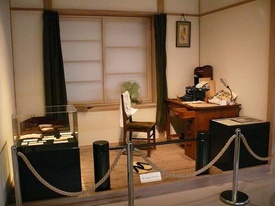

Photo 4: Diorama of a foreign correspondent's typical room (Courtesy of the National Museum of Japanese History)

One example of a foreign correspondent who abandoned his U.S. citizenship was Leslie Nakashima, a Japanese American from Hawaii. He reported the tremendous damage done by the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, as other correspondents did. His newspaper article about the first observation of the devastated city was displayed in the exhibit, as well as other correspondents’ articles. I wondered how their stories had been presented in Japanese history. In order to depict their lives in the story, a diorama of a foreign correspondent's typical room was constructed in the exhibit (Photo 4). This gave visitors an impression of what their lives were like.

The concept of this section seemed slightly awkward at first glance, and it took time until I understood that the curator had included people who were not Japanese but had tried to “stay” in Japan as a counterpart to the Japanese who tried to stay in the U.S. Thus, in terms of featuring “others” in this context, the foreign correspondents were introduced as a significant example of these “others.” Some correspondents were torn when they had to make a decision to stay or return, which reminded me of the male Nisei Japanese at the internment camps who had answered the loyalty questionnaires.

But I think it would have been better if there had been appropriate texts in the introductory part of this exhibit to present the cross-cultural view. Because of the absence of this sort of information, I think the sudden switch of the subject, from “Japanese in America” to “foreign correspondents in Japan,” would inevitably make visitors feel moderate difficulty in following the story-line. However, the spatial organization of the exhibit was designed as selectable, so visitors could skip this section, as it was located in the center of the circular pathway of the exhibit.

Section 4: Bringing the Past to the Present

The type of movement presented in this final section was “resettlement.” The section described and represented the difficulties faced by Japanese Americans after leaving the internment camps for resettlement into U.S. society. For instance, the exhibit included a brochure made by the Committee for Resettlement (1945) that referred to the flow of Japanese Americans from the internment camps as “refugees.”

The section mainly featured two issues to connect the Japanese internment experience to the story-line. One was the whole process of Redress, from the beginning of the movement in the 1960s to the receiving of checks at the individual level beginning in 1994. Another was a film (with Japanese subtitles) entitled "Caught In Between: what to call home in times of war" by Lina Hoshino, which documented a pilgrimage to Tule Lake in July 2002 as one of featurings. The film started with the recent peace gathering of Japanese and Muslims in L.A. to protest the prejudice against Islamic people immediately following the 9/11 attacks. According to Dr. Harayama, there was a little hesitation about the idea of including the 9/11 issue in the exhibit, but eventually he decided to make a connection between Japanese internment and the racial discrimination toward Muslims in the U.S., since he felt a need to bring the past to the present to show the continued presence of common problems.

At the end of last section, there was no ship, but the visitors were brought back to the present time with images of the shuttle bus trip to the Tule Lake internment campsite and the information that some sort of compensation was made by the U.S. government. These were informative historical facts for the Japanese audience that would pressure them to rethink what has been done by the Japanese government for the mistreatment of Japanese American.

Conclusion

As I have observed, in the four major sections of the exhibit ("People on the Move,” “Immigrants and the Outbreak of War between the U.S. and Japan," “Foreign Correspondents in Occupied Japan,” and “Resettlement: Japanese in American Society”), this exhibit was successful in using a broad range of materials to inform visitors about the history of the movement of Japanese immigrants to the U.S. and the movement of people between the two countries. One thing to note is, the inclusion of the additional counterparts, foreigners in wartime Japan, might be considered a weakness by some, but it added an layer of perspective to an exhibit whose focus was people who were not in their native lands. Moreover, the fact that the method of transport between countries at that time was mainly by ship emphasizes how these journeys were inconvenient and how freedom of movement was curtailed because of the difficulty of travel.

Nonetheless, whether this group of people has been considered to be a part of Japanese history until now is a question. The conclusion of this exhibit proposes a new interpretation, namely that there has not been enough attention paid to the "people on the move" in Japan. The exhibit conclusion states:

History is generally written from the viewpoint of 'permanent settlers.' However, actual society does not consist of only 'permanent settlers'…Is it possible to understand history and society through a mixture of various views? This question remains a universal subject in every society through the times" (K. Harayama, Y. Murakawa, T. Yasuda, & M. Yokoyama, 2010).

As far as I have observed, this mention of the need for a new interpretation of history is a rare example of a concluding statement in a Japanese exhibition. It may be because many Japanese curators who work at public museums would be afraid to make a judgment on the exhibition topic, or it may just be because there has never been a custom to do so in Japanese exhibitions. However, after having studied Museum Studies in the U.S., I have had difficulty when I encounter the abrupt end to most exhibits in Japan. Each museum always presents an introduction explaining why the museum planned and designed the exhibit, including an acknowledgement of its co-sponsors, but there is nothing at the end. I think a concluding statement is also needed, as each museum should have its own voice.

This exhibit presented us with a question at the end: a challenge to reconsider history from the perspective of people in between Japan and the U.S. in the past. Therefore, it is safe to say that the dawn of a new interpretation of Japanese history that includes Japanese Americans has begun at the national museum level. As I noted, this may be the first Japanese exhibit at a national institution to bring Japanese people outside their homeland into the mainstream of Japanese history, to acknowledge their history and existence.

After I saw the exhibit, I had a different and more personal realization. This exhibit tried to present the view of people who are in between, like me. Now I am back in Japan, but I have been feeling strange in many situations in Japanese society because I look at ordinary Japanese behavior with a partially American view. On the one hand, I was not an American, nor was I able to express 100% of my thoughts in English during my decade-long stay in Hawaii. Yet my experiences in the U.S. have never left my memory, so I always analyze Japanese people from a partly American and partly Japanese perspective. It is likely that, in whichever country I choose to live in the future, this feeling will remain. Visiting this exhibit at the National Museum of Japanese History was a rare opportunity for me, not only to see this exhibit but also to find greater awareness of a portion of my own self-identity.

Reference

K. Harayama, Y. Murakawa, T.Yasuda, & M. Yokoyama (2010). Japanese Immigratns in the United Status and the War Era, The National Museum of Japanese History, Chiba.

© 2011 Kaori Akiyama