For nearly five years, from late 1946 until his firing by President Truman in April 1951, I had the privilege of serving as personal interpreter-aide to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur. It was an eventful time, a period that was crucial to the recovery of a nation devastated by war, economic hardship, and military tyranny. The work done by MacArthur, and by all who served in the Occupation, was critical in rebuilding Japan, instituting democracy, and planting the seeds for its resurgence as an economic power. Today, in large measure because of the General's leadership in those early days, Japan is a successful example of how American power and generosity can be used to extract genuine friendship and common purpose from even the most bitter of circumstances. I was fortunate to have witnessed aspects of this great undertaking from my vantage point in the Daiichi Insurance Building, MacArthur's general headquarters in downtown Tokyo.

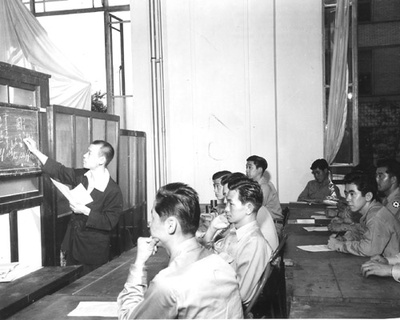

My military service began in February 1941, when I was drafted into the Army from my hometown of Selma, California. I attended basic training with the 153rd Infantry Regiment at Ford Ord, and in 1942, I was reassigned to the new Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage, a secret program to train Japanese linguists to support military operations in the Pacific. I was selected to participate because of my relative proficiency in Japanese, which I had acquired in the few years I had spent in Hiroshima as an elementary school student.

Sending children back to the ancestral homeland for schooling was a typical practice of many Japanese American families at the time, and was based on our Issei parents' desire for their children to carry on Japanese speech, values, and traditions. Despite the difficult transition to a new city and country ・I often got into fights with the local boys because of my foreign status and was beaten by my teachers for not knowing my lessons ・I became much more conversant in Japanese language and culture than I otherwise would have, had I never had the opportunity to live there.

After attending the MIS Language School as a student, I was retained as an NCO instructor until July 1944, when I volunteered to lead a 15-member MIS team in Burma. Two months later, traveling via fast transport by way of Los Angeles, Honolulu and Brisbane, I joined my new outfit, the 124th Cavalry Regiment. The 124th was part of the MARS Task Force that had replaced Merrill's Marauders, which had been decimated by intense behind-the-lines fighting.

My team, including assistant team leader Art Morimitsu, interrogated prisoners, translated captured documents, provided the commanders with a sense of the enemy's mindset, and went on intelligence gathering patrols to eavesdrop on enemy positions. We performed capably and made a positive impact on combat operations, though I grew to hate the conditions: heat, rain, mud, jungle, mosquitos. Burma's rivers and mountains follow a north-south axis, and we always seemed to be traveling east-west, across the rivers and up and down the hills. The latter were often so steep and muddy that we had to cling to the tails of the small Asian donkeys we employed as pack animals.

There is one experience I had in Burma that I have never told before. It took place shortly after I was sent to New Delhi to be commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant. While there, I was assigned to a Colonel Blunda, who was directed to return to Burma to join up, and serve as the American liaison, with British forces in Mandalay. When we arrived, the Colonel obtained information that indicated the Japanese were in retreat and had abandoned Rangoon. The British were unsure of the intelligence and wanted to advance cautiously, but the Colonel, an impatient and flamboyant type, decided to proceed alone (with me and a handful of Nisei linguists) to "reconnoiter" the security situation.

With great trepidation, the rest of us jumped into our jeeps after him and drove pell-mell down the road, at last pulling into Rangoon. Sure enough, the city was empty of Japanese troops. Colonel Blunda immediately convened the local leaders and conducted an inspection of city facilities, including the bank. We were, almost certainly, the first Americans, and perhaps the first Allies, to "liberate" and occupy Rangoon -- at any rate well ahead of the main body of British forces. It is possible that British scouts or other elements had been there before us, but they were not in evidence when we got there. I heard later that this stunt, which naturally infuriated and embarrassed the British, got the Colonel into trouble and resulted in his being sent home early to the states.

Near the end of my overseas service, I, along with fellow MISer Lt. Eddie Mitsukado, was attached to British Army 34th Indian Corps in Ceylon as an American liaison officer. My job was to provide the Corps with language capability in the invasion of Malaya. The 34th's mission was to effect a landing in Port Dickinson near Kuala Lumpur. We arrived with no resistance, which was puzzling until we discovered that Emperor Hirohito had accepted the Allied surrender terms that very day: the Japanese forces were waiting to surrender to us in Kuala Lumpur, 25 miles inland. I remember that the only casualties we suffered were a couple of tanks and trucks that we lost to quicksand during the night. I assisted with prisoners, documents, and the surrender generally, and later obtained permission to visit Singapore to see how the rest of the surrender was proceeding. The whole action with 34th Corps lasted a month.

Shortly thereafter I received my orders to return home. I left Karachi aboard the SS Santa Rosa, a converted luxury liner that returned me and other officers and civilians from service in the China-Burma-India theater. I recall that it was a long voyage, but one made bearable by the bevy of pretty nurses onboard and the prospect of returning stateside. After disembarking in New York, I was assigned to the Washington Document Center (later part of the Central Intelligence Group and CIA) in Washington, D.C., where I processed Japanese documents as a research analyst. I remember that Washington was not to my liking -- for one thing, it was too expensive -- and when the opportunity arose a few weeks later, I volunteered for duty in Japan. I had another motivation too: I was curious how Japan was faring in the war's aftermath.

I arrived in Yokohama via Seattle in the fall of 1946. I was initially assigned to a requisition depot, but was soon asked to interview for the position of interpreter-aide to MacArthur. The position was open, to my recollection, because the highly capable Shiro Omata, who had served in this position for several months prior to my arrival in Japan, had taken home leave and the position needed to be filled. The interview was conducted by Colonel Herbert Wheeler and Colonel Larry Bunker, his aides-de-camps, who were apparently satisfied by my background and qualifications.

I first met General MacArthur in his plain office in the Daiichi Insurance Building, one of the few large structures to survive the wartime bombing intact. He was smoking his famous corncob pipe as Colonel Wheeler introduced me. The General was very gracious: he shook my hand and welcomed me aboard.

I was assigned to a space in a large administrative filing room off the ADCs' offices, along with some sergeants and warrant officers. At first, I attempted to translate all the Japanese memos and documents that the General would review; however, the task was overwhelming, and I soon learned the trick of sending them on for translation to G-2. With Colonel Wheeler's support, I began to reorient my duties more toward interpretation and away from translation. Colonel Wheeler made sure that I was easily accessible to the General at all times.

My personal impression of General MacArthur was that he was a brilliant man, and also a bit of a showman. For example, whenever he met met with a Japanese VIP, he made a show of displaying some knowledge of the visitor. He read the visitor's background file before any meeting, and thus was often able to add a personal touch to the visits. He also liked to impress people with his outgoing ways, although his was not a backslapping, hail-fellow-well-met personality ・in fact, I cannot remember a single joke he made. He was much older than other generals (he had served as Army Chief of Staff well before the war), and formal and dignified in his bearing, attributes that were much appreciated by the Japanese, who tend to place much stock in these characteristics.

As the first foreign "conqueror" in Japan's history, the General's public persona also benefited from the people's reverence for authority. During this period, some Japanese embraced Japan's defeat and wanted to become part of the United States; quite a few letters and petitions were brought to this effect. It is to his credit that even when he was fired, the General refused to disparage his superiors, including President Truman: he comported himself like a gentleman at all times. Of course, there was a lot of infighting between the President's and the General's subordinates which I believe helped sour their relationship.

Being MacArthur's interpreter meant that I also effectively served as a liaison officer. I had contact with palace and government officials, but I also had the chance to talk informally with local people. Headquarters discouraged fraternization with the local populace, but in some cases it was unavoidable. These conversations afforded me insight into the common man's viewpoint and helped me better appreciate the political and economic situation, which enhanced my interpreting. Most Japanese treated us cordially, though there must have been some resentment of the American occupiers. Overall, I think the Japanese people were grateful that we were not treating them as harshly as they themselves might have treated us, if the tables had been turned.

At this time, Tokyo was a devastated city. Bombs and fires had leveled much of the metropolis, countless citizens were living in temporary wooden structures; it was only until 1948 or 1949 that the city began to recover. Food was a problem too; many people did not have even basic staples like rice. Cigarettes, of course, were an unobtainable luxury. It was common sight to see people scrounging in the gutters for cigarette butts discarded by GIs. Even high officials knew deprivation; on several occasions, I felt compelled to offer c-rations to officials of the imperial household. But somehow the citizens of Tokyo managed a bare living, despite the hard times, and it is a testament to their fortitude and work ethic that they survived and eventually thrived.

After an initial slow period, as the Japanese government gradually took shape, General MacArthur began increasingly to require interpretation services. Beginning in early in 1947, many Japanese officials came to visit. Courtesy calls were made by Supreme Court justices, Diet members, and Bank of Japan presidents. Successive Prime Ministers scheduled interviews with him. One of them, Prime Minister Yoshida, spoke some English and often tried to bypass me by meeting alone with the General. This ploy allowed Yoshida to claim that he had MacArthur's blessing for this or that, without having anybody contradict him.

Another visitor was the chairman of the Lower House of the Diet. I remember seeing tears of gratitude in his eyes as I interpreted MacArthur's assurance to him that in the future, Japan could exercise its democratic prerogative to change its constitution to deploy military forces to defend itself from attack. Ultimately, as we know, Japan did in fact establish a self defense force.

In carrying out my duties, I tried to make sure that the words I interpreted were correct in spirit and tone as well as content; I also tried to convey the cultural context. It was very important to include these nuances because the Japanese were extremely sensitive to MacArthur; his views carried great weight, similar to those of the Emperor.

MacArthur himself was respectful of the institution of the monarchy. He understood on a deep level the degree to which the Japanese Emperor was revered by the populace at that time. It is ironic that MacArthur's own stature, in comparison, undoubtedly contributed to the diminishment of the imperial office in the eyes of modern day Japanese. Nevertheless, MacArthur made every effort to protect Hirohito and his prerogatives, including an instance in which I played a small role.

When the American press was besieging the Emperor with unprecedented requests for interviews, palace officials became worried that MacArthur would be angry if the requests were denied. The General decided to send me to deliver a personal message to the Emperor to allay such fears. MacArthur wanted to convey to Hirohito that he had a right to privacy, just like any other citizen, and that he did not have to meet with the journalists if he did not wish to.

Arrangements were made between the chancellery and the General's staff for me to meet the Emperor alone, an unprecedented occurrence. To anyone's knowledge, no individual had ever met with the Emperor before in private audience, without any retainers. I was aware of this singular fact when I drove myself at 7:30 in the evening to the Sakuradamon gate of the palace, a complex of graceful buildings in the heart of Tokyo surrounded by wide moat. I was ushered into an ante room and asked to wait. A few minutes later, Hirohito entered, a small man in a conservative suit. He motioned me to sit across from him at a small round table.

I delivered MacArthur's message, intensely aware of the irony of the situation: I, an American Nisei, only one generation removed from Japan, was having a conversation with a man who, until recently, was considered a divinity. I could not help but remember an instance during my youth in Hiroshima when all the students were pulled out of school to greet then Prince Hirohito at the train station. We had gathered there in front of the station, hundreds perhaps thousands of us, all required to bow, prohibited from lifting our eyes from the ground, as the god-incarnation entered and left the station. I remember trying to look up, to get a glimpse of him, before getting slapped down by a teacher for my disrespect. Now, here I was, years later, dressed in the uniform of Japan's conqueror, talking across a small table to the same personage, like an equal. Nothing could speak more eloquently of changes that had occurred in those intervening years or the difference between my life as it could have been had my parents not emigrated from Japan and my life as an American.

At the end of the audience, the Emperor thanked me for the message, and then inquired about my family. I told him that we were from California, but that we had originally come from Hiroshima. He then expressed appreciation for the work of the Nisei in Japan. "You are a bridge between our two nations," he said. He then took his leave, disappearing through a side door, and I crossed over the moat that divided the palace from the rest of the world.

Of all my experiences as MacArthur's interpreter, my meeting with the Emperor was the most memorable. Hirohito's words reflected my own thoughts on the value of the Nisei to the U.S.-Japan relationship. It is true that without Japanese Americans, the Occupation of Japan would not have gone as smoothly. This was particularly so at the prefectural and municipal level, where the linguistic skills of Japanese Americans proved invaluable in clarifying American intentions and control over every aspect of governance, from the teaching of democratic ideals in schools to reforming farm ownership practices. At the national level, Nisei were involved in facilitating security and economic policies and the development of a new constitutional and legal framework. They were the communications link between the occupiers and the occupied; they were the oil that minimized friction in the gears of the Occupation machinery. In short, the Nisei were integral to the success of the Occupation; they had an impact that lasts right up to the present.

There were other duties that I undertook for the General, memorable in their own ways. Once I delivered another message from MacArthur, this time to the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Convention, congratulating the peace-minded organizers and participants. I remember thinking that sending a message on the subject of the atomic bomb was unwise, since U.S. policy was not to comment about any aspect of atomic policy. Nevertheless, I had my own thoughts about the bomb, insofar as the devastation of Hiroshima had a direct, personal impact.

As I have noted, my family hailed from the city and I had many relatives there. Some were killed, of course, by the blast, and others were maimed, including a close cousin who had been blinded and burned by the radiation and who had undergone dozens of medical procedures to ease her pain. Despite my revulsion at Japan's role in the war, I have always believed that we bombed Hiroshima less out of necessity than because we could ・we wanted to see if it worked. I also believe that at some level, the decision was racially motivated ・I do not believe we would have been prepared to use atomic weapons against Germany, for example.

But the Hiroshima trip yielded an important benefit. During the train ride back, I noticed an attractive girl, a Nisei from Honolulu it turned out, a few rows up. I rolled some oranges down the aisle to get her attention. I ended up marrying her.

I was still assigned to the General when he was fired by President Truman. The word came when he was home having lunch. Colonel Bunker showed him the telegram, and according to what the Colonel told us later, MacArthur did not say anything. No loud outcry, no protest. He may have been expecting it one way or another.

His last acts were to help his staff. For myself, he made sure that I received orders to go to the Counterintelligence Corps at Fort Holabird, in Baltimore, as I had requested. It was typical of the General to take care of his staff. Shortly before, he had personally signed the recommendation for my promotion to Captain, an unusual honor for a field grade officer. So it was no surprise that all of us on his personal staff chose to depart with him when he left Japan, after a memorable departure ceremony at Haneda Field. I was on the second plane with the other aides following the plane carrying MacArthur and his wife, child, and nurse.

A last word concerning the Occupation: I strongly feel that we should never lose a war, because the enemy will come and take over the place, just as we did. We were lucky in having the Japanese government administrative capabilities intact. We used the Japanese government as an instrument of our will. MacArthur had the luxury of making pronouncements that were carried out without question by the Japanese government, even on such contentious issues as labor strikes. It was a successful Occupation because we refrained from meddling except at the top level. We were also fortunate in that Japan obeyed the Emperor in surrendering and obeyed the Occupation powers in defeat. We learned the value of not being a harsh victor. It is a lesson that has paid dividends for our nation in the 54 years since the end of that great conflict, and one that we would do well to remember in this new century.

* This article is one of the winning entries from the 2004 essay contest of National Japanese American Veterans Council, which invited MIS veterans, or their families, who describe their post-war experiences in their role as American occupiers of the country from which their parents had emigrated.

© 2005 Kan Tagami