I was born in Japan. My birth name is Murase Ichiro [村瀬一郎]. My obaachan proposed “Ichiro”—a name not uncommon for a first-born male, but she also had another reason. My grandmother, who taught at Kyoritsu Women’s University in Tokyo, had been a friend of the mother of Hatoyama Ichirō, a Japanese politician who later headed the center-right Liberal Democratic Party and became the Prime Minister of Japan. (He’d be turning in his grave to know that a person with progressive, left-leaning politics was named after him.)

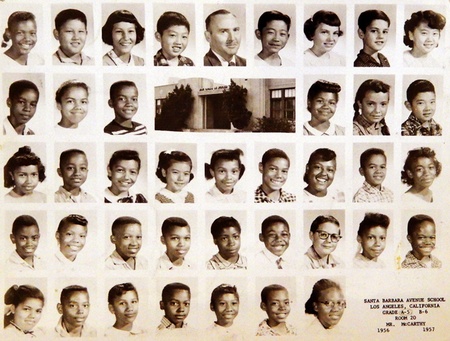

When I came to America at age nine, we first lived in South Central in a mostly African American neighborhood. A handful of Japanese American families resettled in the area after wartime concentration camps a decade earlier. A Niseigardener named George Sato and his wife Mary lived across the street with their children, Kenny and Arlene. They were expecting a third child, and had decided on two names for the baby-to-come: If the newborn were a boy, he would be “Michael” and if a girl, she would be named “Donna.” It turned out to be a girl.

When I was to be naturalized at age 13, I had the opportunity to change my legal name without the usual red tape or additional cost. The Satos offered up their unused boy’s name, “Michael,” as my American name. The idea of a new name was not something my struggling immigrant parents had given a lot of thought to. They left it up to me to decide, so I agreed to rename myself “Michael.”

After a few weeks of trying out the new name at my junior high school, I started to regret my choice. Still with the listening “ear” of a native Japanese speaker, every time somebody called me “Michael” (/ “MY”-kull /), I heard “Maiko,” a Japanese girl’s name, like Akiko, Fumiko, and Yoshiko. I did not want a girl’s name!

When I explained my ambivalence about the name to Mr. Sato, he nonchalantly said, “Well, why don’t you just be ‘Mike?’” I wasn’t crazy about Mike either, but I thought, at least it didn’t sound like a girl’s name.

I should add here that, over the years, I met many JAs whose actual names were diminutives: a Bob who wasn’t Robert; a Dick who wasn’t Richard; and a Jack who was just Jack.

When it came time to fill out the naturalization paperwork, there were lines for my Last, First, and Middle Names. It hadn’t crossed my mind, but I had the option to change my family name as well. My parents would’ve probably had something to say about that. Then I had to decide which would be my First Name and which would be Middle. Again, the Satos described how many Nisei gave their offspring American (English) names so as not to sound Japanesey, hinting that “Mike” come first. I wasn’t quite prepared to demote the name I was born with so I chose to be “Ichiro Mike Murase.”

Even though I wasn’t wildly ecstatic about any of the three components of my name, I felt I had gone through a rite of passage of sorts into a new stage of my life. Apart from being sworn in as a bona fide U.S. citizen, I aquired a new legal name if not quite a new identity.

My schoolmates—most of them Black, and even Sansei—felt more comfortable calling me “Mike” rather than sounding out the name “Ichiro.” And I was fine with that. It fit the acculturation/Americanization process I was undergoing through middle and high school years.

On another tangent, my father’s name was Hide Murase. Since he was already a U.S. citizen, he didn’t have the option of changing his name so he tolerated his boss and co-workers calling him “Heidi,” a fictional Swiss girl’s name. I would often tell my dad, “Don’t let them call you Heidi. Correct them. Tell them it’s ‘Hide’ (pronounced hee-day).” But my dad was not the confrontational type. As a Kibei migrant, he had learned to cope with much worse indignities than how his name was said.

It wasn’t until years later in 2001 when Ichiro Suzuki—the Japanese dai-riigu sensation—became the first position player of Japanese descent to play in America’s Major Leagues that I remember my first name being said aloud on a regular basis. The Seattle Mariners had decided to market him mononymously as “Ichiro” (ee-chee-row) rather than refer to him by his last name Suzuki as is customary. Within a few seasons, Ichiro had broken many batting records, made the All-Star team, and became a merchandising standout. But by then, my day-to-day identity was firmly set as Mike Murase and used my full name, Ichiro Mike Murase, only in financial and legal contexts. And to this day, my own mother is the only person who calls me “Ichiro.”

In the U.S., we live in a diverse multicultural, multilingual society. People with names like Martinez, Wong, Nzinga, Krikorian, Stanislawski, Nguyen, Ch'ae, and thousands more live in L.A. Most of us forgive each other’s occasional mispronounced names (unless there is a reason to suspect intentional, racial motives for this) and we ourselves struggle with strangers’ unfamiliar names.

For many years, in managing the local office of a Congresswoman, I was exposed to the diverse polyglot constituency she represented. As an elected official, my boss attended many meetings and spoke at various functions, piquing some civic-minded people’s interest in communicating with the Congresswoman further. Many follow-up conversations were delegated to staffer Mike Murase. The Congresswoman would deflect bum-rushing crowds by yelling out, “Talk to Mike Moo-ra-see (phonetic).” “Give Mike Moo-ra-see your name and we will follow up.” No one would dare ask the Congresswoman to spell out my name. They would just do their best to remember the sound of my name or write it out on paper.

Back at the office, I would be flooded with letters addressed to the Congresswoman. The letters often had the line: “Attention” followed by some variation of my name. Mike Murasi was common. There were others like: Mike Rossi, Mike Marusi, Mike Morissey, Mike Muraski, and a couple dozen others.

Some constituents wanted to talk with my boss and would find my name in a directory or see it in print in some document: Mike Murase, District Director. Residents, voters, and lobbyists would call the office and ask for me, but they would often make my last name rhyme with “horse race.”

“Hello, is this Mike Murāse?”

“Yes, this is Mike Murase. May I help you?”

“Oh sorry. It’s not Murāse? What kind of name is that?”

“It’s okay, but it’s pronounced moo-rah-say,” I would say slowly. “I’m a Japanese American.”

Eventually, we would move past small talk about my name on to the purpose of the phone call.

When all is said and done, in the words of Shakespeare, “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

© 2014 Mike Murase