Read Part 1 >>

August 5th, Hiroshima

I have recently been looking for some answers about how to live “correctly”—meaning, I suppose, with personal integrity and respect for all people and nature. I’ve read quite a bit along these lines: Buddhism, Shintoism, Hinduism, the Koran, and Bahai faith and even the pleasure of talking occasionally with a Jehovah Witness fellow who is always kind enough to drop off free copies of the “Watch Tower” for me.

I am a product of a cynical age, having come of age (to some extent) in the nineties. I’ve seen friends become successful and others continue to be involved in a sincere struggle to find something other than that prescribed by materialistic ideology. I’ve also come to realize that money, higher education, or social status really have nothing to do with happiness, nor, sadly, does simply understanding these truths open the doors of happiness.

Oddly enough, I get more of a sense of hope here in Japan. The message is something that I think can only come from a country within whose borders civilians suffered, since, indeed, where else does this passion come from to tirelessly fight for justice but from understanding what it is like to be bombed, homeless and hungry, first hand?

The beginning of August is a busy time of festivals all over Japan. In Sendai, we have “Tanabata”. Nearby Akita “Kanto” and Aomori “Nebuta”. This all precedes O-Bon, a summer solstice period, in the middle of August, when families welcome back the spirits of deceased relatives, tend to family graves, and make offering of incense, flowers, liquor, and favorite foods.

I check into the “Chanter” Hotel where I am booked for the next three nights. The place is a “wedding hotel.” The second and third floors have chapels to accommodate wedding parties. This is a truly weird (but popular) side of Japan that is the product of watching too many Hollywood movies and having money to indulge their absurd fantasies. Many Japanese women want to have a “Christian style” ceremony. The wedding march, white gown, Christian preacher. The whole bit, even if they aren’t Christian! It doesn’t even matter if the priest is a priest. This is a very big business in Japan. I knew one Assistant Language Teacher who, despite having a big crop of orange hair and beard, did quite well for himself by posing on weekends as a priest.

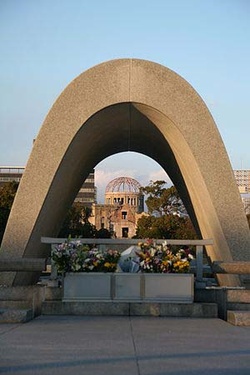

The Peace Park is a short stroll from the hotel. The day is heating up. Japanese summers are especially oppressive in the western part of the country. Dry heat is unheard of here. I walk over to Aioi dori, the main east-west downtown road where street cars are constantly rattling by. I follow the line, past a recently bankrupt SOGO department store. The city is a little larger than Sendai, but seems older somehow. The streets are full of salary men and uniformed OLs [office ladies]. As I near the Peace Park, the first thing to come into sight is the famous Atomic Bomb Dome, the twisted metal roof supports being the only remnant the “dome”. It’s an awesome sight; a clear, striking image of the Atomic Age that is now an international symbol.

I paused on the Aioi bridge for a while meditating on the sight. The images that come to mind are pictures and descriptions of and by victims of the horrors that took place here. I recently read “Exposure: Victims of Radiation Speak Out” by the Chugoku Newspaper; “Hibakusha” a collection of stories of the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and “The Day Man Lost: Hiroshima, 6 August, 1945” by the Pacific War Research Society.

The further away from the actual human experience I read, the stronger the rationalization supporting the dropping of the A-bomb gets. Who do you believe? Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivors) is the most recent book I read, first hand accounts of victims and survivors, the images of the river being filled with dead and dying, bloated, charred black bodies, the moaning, the unbearable agony of suffering welled up from the now placid Otagawa River that flowed before me, the site that once had become a hell on earth somehow transformed into an Eden.

“We’re all victims of the logic of war,” writes Kazutoshi Hando, former chairman of the Pacific War Research Society. “A logic that permits each belligerent to claim that he has ‘justice’ and ‘right’ on his side, but a logic that is of course solely dictated by national and personal interests.

That is intrinsic to the nature of war—war is waged by sovereign states; sovereign states are governed by men; men who govern states are too often governed in turn by the lust for power; and the axiom that power corrupts is no longer to question.

There is quite a bit of activity at the park. Dozens of groups of summer-vacationing school kids are accompanied by banner toting teachers, some are stopped in front of monuments, giving explanations to attentive students, groups of adults following pretty flag toting guides frantically rushing here and there to make sure their group of seniors stays together. I’m impressed that this area is such a magnet for peace conscious people. The international mix of people is heartening as well. I can pick out accents of all sorts, but the common language is most certainly English.

I peruse the map that I pick up at the information office that is on the grounds. What strikes me first is the accuracy of the bomb drop site, a little north, but dead in the heart of the delta area composed, from west and east, of the Otagawa Hosuiro River; Tenmagawa; Otagawa (Hongawa); Motoyasugawa, Kyobashigawa; then, finally, the Enkogawa, on the eastern border of Hiroshima city.

My impending visit to the Peace Memorial Museum follows a lifetime of seeing Hiroshima images on TV, the NFB and PBS documentaries that attempt to quiet the guilty conscience of the winners of the war, the textbook pictures and anniversary testimonials of survivor and reports of those like myself who are drawn to Hiroshima, to bear witness, to report on the state of a city that suffered for all of us.

I don’t consider myself to be a peace activist. Like most of my peers I believe that I don’t possess any deep sense of nationalism or even an ideology that would compel me to fight in a war of any kind.

The museum is busy on August 5th. I pay the 50 yen admission. The place is busy with groups of school kids taking their summer vacations from all over Japan and foreigners traveling mostly in couples or small groups. The East Building’s first floor begins with “Why was the A-bomb dropped on Hiroshima?” The explanation in their section are remarkably detached, clinical, academic in tone. No finger pointing or blame mongering.

*This article was originally published in the September 2000 issue of the Nikkei Voice.

© 2000 Norm Ibuki