Read part 3 >>

By late December of 1941, the armed services ceased accepting Japanese Americans either as volunteers or draftees, even though the Selective Service Act barred discrimination. Consistent with this discriminatory policy, Nisei were classified not as 1-A, but rather as 4-C, the classification assigned to “enemy aliens.”

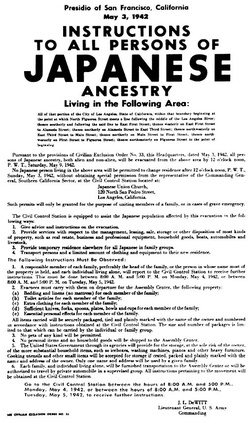

Woodcut of “No Japs Wanted Any More” (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

In response to a great deal of agitation from the old anti-Japanese forces in California and elsewhere on the West Coast and in scattered parts of the United States, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which, as a matter of “military necessity,” authorized the army to exclude “any and all persons” from as yet unspecified “military areas.” Those military areas turned out to be the southern part of Arizona and the western halves of the states of Washington, Oregon, and California.

Initially, the government urged Nikkei to voluntarily relocate themselves out of the military areas and to resettle east of them. Most Californians, including Orange Countians, who had the wherewithal and inclination to relocate and resettle chose to do so in the eastern half of California, which was then designated as a “free zone.”

Accordingly, the Masuda family moved from the ten-acre homestead in Fountain Valley (which the family had just shortly before purchased in the name of one of the Nisei children) and settled in Fresno, where one of the married daughters lived and maintained a vineyard. Because the Masuda family owned a new car, a 1941 Ford, as well as a truck and farm equipment that were in good condition, they took all of these items with them to Fresno. There, before too long, the family was joined by Gensuke, who had been released from the Missoula internment camp, no doubt because of the letter of protest that Kaz had sent to the government coupled with the fact that the Masudas had two sons serving in the U.S. Army.

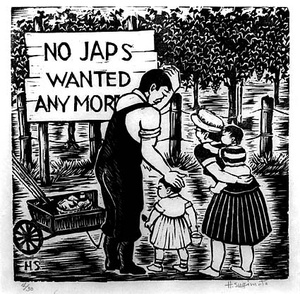

When the government decided to extend the military area in California from its western half to the entire state, the Masuda family, as with so many other Nikkei families, lacked the means to undertake another move that would take them outside of the military areas. When the government decided to end so-called “voluntary resettlement” for Japanese Americans and instead institute the forced mass incarceration of the entire Nikkei population, aliens and citizens alike, first in temporary “assembly centers,” located in the West Coast region, and afterwards in permanent “relocation centers,” mostly situated in the Interior West region. All of these facilities wore the trappings of concentration camps: armed guard towers, barbed-wire fences, and pervasive surveillance.

In the case of the Masudas, they were duly imprisoned in the Fresno Assembly Center, where they remained with mostly incarcerated northern California Nikkei for nearly two months before being transferred to the forested, rattlesnake-infested Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas, where the summer temperatures soared to above 100 degrees and the winter months brought temperatures of below 20 degrees. They stayed at Jerome for almost 20 months, until the government closed it in June 1944, after which they were transferred to the Gila River Relocation Center in the scorching hot and dry desert of Arizona, where they stayed until moving back to their Talbert home in July 1945, one month before the atomic-bombing-induced surrender of Japan to the United States brought an end to World War II.

Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

As for Kazuo Masuda (about whom we will soon hear more), after Pearl Harbor, although he was not summarily discharged and assigned an alien enemy status like most Nisei soldiers, he was transferred to a non-essential duty as a gardener. Then, too, although a top graduate of a radio class receiving instruction in Morse code and theory, Kazuo was not accepted for service in the Signal Corps.

While such discriminatory treatment brought Kazuo acute disappointment, it fell short of the humiliation experienced by Nisei soldiers stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas. When President Roosevelt visited that camp, they were herded under gunpoint into a plane hanger, which was surrounded on the outside by machine guns and tanks, and ordered to remain silent and to look straight ahead for four hours, until the president had departed Fort Riley.

Time limitations will not permit an in-depth treatment by me of the World War II military experience of Japanese Americans, but here are a few key points that will help to contextualize the experience of Kazuo Masuda.

In early 1943, the American government reversed its policy on military service. The Japanese government had been making effective propaganda in Asia out of the incarceration of Japanese Americans; the camps appeared to confirm their depiction of war as a racial conflict. To respond to the Japanese propaganda, and under pressure from some Japanese Americans, most notably the Japanese American Citizens League leadership, and civil liberties organizations, President Roosevelt authorized the enlistment of Japanese Americans into the U.S. Armed Forces. Japanese Americans were now permitted to form a special segregated infantry outfit, the unit which would come to be called the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team.

In Hawai‘i, where Japanese Americans had not experienced mass eviction and incarceration, recruitment exceeded all expectations; instead of the 1,500 volunteers anticipated, 10,000 volunteers turned up at the recruiting offices, of which 2,645 men were selected. This situation was much different from that which occurred in the ten mainland War Relocation Authority-administered detention centers incarcerating Nikkei, where the response of 1,300 volunteers for the new all-Japanese American unit was decidedly “underwhelming.”

By June 1944, the men who signed on with the 442nd found themselves in Italy fighting alongside the 100th Infantry Battalion, a battle-tested unit made up mostly of Japanese Americans from Hawai‘i. The 100th had been formed in 1942, before the ban had been placed on the enlistment of Japanese Americans, and they had seen action in North Africa and Italy, and for months the men in this unit had distinguished themselves in repeated assaults on the German lines as the Allies fought northward in Italy. The 100th had lost so many men that they came to be called the “Purple Heart Battalion.” The fall of Rome in June 1944 had boosted Allied morale, but it had not ended warfare in Italy, and new troops were needed to fight the Germans. As the campaign in Italy continued into the summer, the newcomers of the 442nd and the combat-wise survivors of the 100th would be asked to spearhead the Fifth Army’s drive northward from Rome.

Kazuo Masuda was one of these newcomers. After training at Fort Ord, he had moved on to Camp Crowder, Missouri, and then to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where he received combat training and was assigned as a staff sergeant to Company F, 2nd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Before leaving for combat in Italy, Kazuo took advantage of a furlough to visit his family at their Jerome detention camp barracks residence.

Kazuo Masuda Visiting Family at Jerome Camp (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

While stationed in Italy in 1944, Masuda, then 24, wrote to his niece at the Gila River camp, to which the Masuda family had moved since his visit with them at Jerome. “I sure do hope the war will end soon so I can see you and all the people I used to know,” he wrote. “When I come back, I will tell you about my experiences. Goodbye, and write again soon. Sincerely, Uncle Kaz.”

Takashi Masuda in Army Uniform (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

Kaz was killed less than a month later. On August 27, 1944, while leading a patrol across the Arno River in Italy, Staff Sergeant Kazuo Masuda encountered a German machine gun nest. He fired 18 rounds from his Thompson submachine gun before he was cut down by the German machine gun bullets.

Ironically, Kazuo’s brother Takashi, a replacement member of Company A of the 100th Infantry Battalion, had shortly thereafter come by to visit his brother at the Arno River encampment, utterly unaware of Kazuo’s death.

When informed of this situation, Takashi first paid his respects at Kazuo’s gravesite and then, a few days later, sought and was approved to take Kazuo’s place in the 4th platoon. Sadly, on November 3, 1944, Takashi himself was wounded in action while in combat at Bruyeres, France.

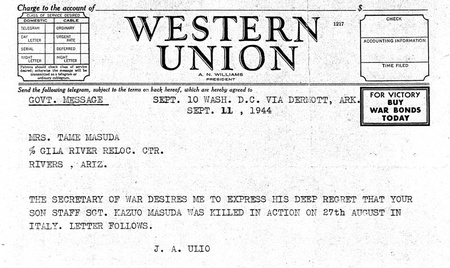

A third Masuda Nisei, Masao, before reporting to basic training and undertaking duty in the Military Intelligence Service, was visiting his detained family at the Gila River camp in Arizona, when he was handed a telegram bearing the tragic news that Kazuo had been killed in action.

Masao then handed this telegram to his sister Mary so that she could read its sad contents to their parents.

Western Union Telegram, Kazuo Masuda Death (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

* This was a presentation at a public program in support of New Birth of Freedom: Civil War to Civil Rights in California at the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, Fullerton Arboretum, California State University, Fullerton on October 19, 2011

© 2011 Arthur A. Hansen