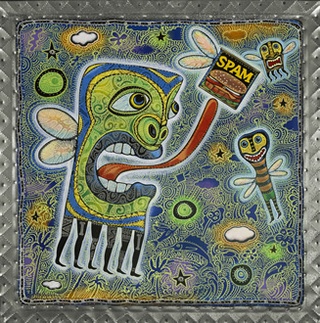

A giant fly hovers, poised on translucent wings that appear too small to support his weight, his face a bright, whimsical Tiki mask in shades of blue, green, and yellow. Protruding from his body are three pairs of human-like legs in black and gray patterned tights. In the distance, his friends watch, their faces frozen in horror and amusement. The fly’s eyes burn with concentration as his tongue strains toward his prey: a winged, rectangular can of Spam.

This is Joel Nakamura’s painting, “Unnatural Selection,” and like the rest of his work, it has the uncommon ability to capture an audience with its vibrant weirdness. In this one painting, an entire story waits to unfold—Nakamura’s finished product comes across as an invitation to viewers to let their own imaginations pick up the narrative where he left off. Taking influence from the stories and artistic techniques of numerous cultures, Nakamura creates a compelling world, retelling myths that have existed for generations while adding to them the lighthearted, accessible, and even provocative touch of modern popular culture.

“I was always interested in the strange, the bizarre, the unusual,” says Nakamura, a 51-year-old Sansei. “I liked any TV show narrated by, or starring Leonard Nimoy.” The artist grew up in Whittier, California—a suburb of Los Angeles that he describes as “the hometown of Richard Nixon”—and graduated from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. His fascination with the uncommon drew him to leave Southern California for Santa Fe, New Mexico, a town steeped in Native American and Spanish cultural history. “You can’t help but be influenced by the environment here,” he says. “It is a very creative place.”

Joel Nakamura’s artwork, largely done with polymer paints on tin, draws from the tradition of Spanish tin arts and retablos (devotional icon paintings), as well as Native American petroglyphs (cave paintings), both of which are part of the New Mexican landscape. Many of his paintings share the characteristically expressive shapes of local petroglyphs, such as his playful work, “The Hunter and the Hunted,” which pictures an early hunter running with a spear as he is chased by a humorless, blue alien in a spaceship.

"'The Hunter and the Hunted' is a what if kind of story," says Nakamura. "I like to begin with a story to build around. I particularly like stories of cryptozoology-- Cupacabras, Bigfoot, ghost stories."

The inclination to bring different cultural elements together in his artwork comes from Nakamura’s own multicultural American experience. During WWII, his Nisei parents spent time in the Japanese American concentration camps, and though they never spoke about their wartime experiences with bitterness, they did make an attempt to fit into mainstream American culture. Added to this, the fact that there were few other Asians in Whittier at the time meant that “of course we ate some Japanese food, like tempura and noodles, and we participated in some traditions, but my family tried very hard to blend,” Nakamura explains. “I think to some degree our eyes turned away from Japan.” Raised with limited knowledge of Japanese culture, he instead remembers trips with his parents to visit museums, art exhibitions, cultural events, and ruins, including the ancient Pueblo dwellings of Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. Through these experiences, he developed a deep appreciation for folk art that only grew with time. Now a reader and admirer of Joseph Campbell, renowned writer and mythologist, Nakamura draws insight from Campbell’s reflection, “myths are public dreams and dreams are private myths.”

This sentiment, that myths are shared dreams that unite peoples, pervades Nakamura’s work. His paintings convey a genuine fascination and curiosity, and in them, through color and movement, ancient myths return to life. Whether or not we recognize the stories they tell, the images he creates appeal to the senses and impart Nakamura’s own enthusiasm to his audience.

In his painting, “African Myth: How Man Got Fire,” Nakamura presents a praying mantis, her shape and position comically exaggerated. Her eyes bulge and though her mouth is full of menacing insect teeth, something about her expression appears concerned. She rubs her front legs together and from that friction springs a fire whose warm glow encircles the mantis’s entire body. Behind her, a man and an ostrich run across the African savannah.

The average person knows no more about this story than what Nakamura provides in his title, but that doesn’t matter. Everything about the painting engages—the color, the hidden patterns in the leaves and the glow of the fire, even the insect’s cryptic expression. Rather than treat myths as artifacts to be handled delicately, Joel Nakamura takes liberties, mixing narratives and styles from vastly different sources and bringing them together with humor and compassion.

His works need no context, and because they have the power to stand alone, they also have the power to instill a sense of curiosity in viewers, leading them to investigate these myths on their own. In this way, Nakamura’s artwork plays a role in preserving stories that may otherwise be lost in time.

“I think there is always a danger in forgetting who we are as a culture and as people of color,” he says. “We try hard to assimilate into western culture.” The forced Americanization of people of Japanese heritage during WWII is certainly an example of this assimilation. Just as Native American culture has been stripped away throughout American history, Japanese American communities also underwent a forced change during the war, leaving future generations disconnected from the cultural narratives of their parents and grandparents. Nakamura says that, growing up, he knew only Japanese words for food, as well as a few token bad words. Years later, he is making an attempt to get in touch with his roots. “I am learning to become more Japanese for the first time through my practice of a ikido, a Japanese martial art,” he says. “Now my Japanese is made up of aikido terminology—and I can count to thirty-one.”

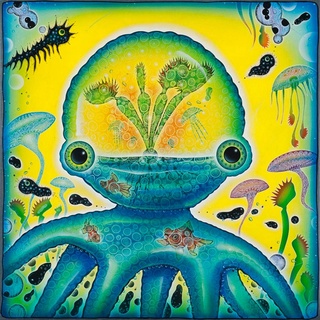

His Japanese heritage also provides Nakamura with artistic inspiration. “I am very taken by the J-pop movement in art,” he says, a movement which includes modern artists such as Takashi Murakami and Yoshimoto Nara as well as retro icons like Godzilla and Ultraman. He has also experimented with forms of Japanese folk art such as daruma and kokeshi dolls. The results, works with titles like “Blue Godzilla,” “Ultraman,” and “Tako Rikishi (Octopus Sumo),” are visually stunning hybrids that combine the simplicity of traditional Japanese forms with the bold colors and imaginative designs for which Nakamura is known.

“Sakura Dreams,” embodies this mixture. The name of this striking kokeshi doll is a combination of Japanese and English and, though the cherry blossoms painted on her body are a universally-recognized symbol of Japan, the dreamy style of her face feels distinctly Southwestern. “Sakura Dreams,” like Joel Nakamura and a rapidly growing number of people in the United States, is an American blend, a product of an increasingly multicultural, globalized society.

In this kind of society, it is easy for people’s stories to fall between the cracks or to be eclipsed by the dominant western narrative. For Nakamura, art is a way to preserve identity—both his own and those of cultures whose folklore is in danger of being forgotten. “The danger is that we are now identified by what we consume more than what we produce as a nation,” he says. “As artists we can at least have the ability to be identified by what we produce. I try hard to preserve stories as visual mythology for many cultures.”

“[Nakamura] is a mythmaker of enormous talent,” says critic Matthew Porter in a 2006 review of the artist. “What [his paintings] really are is one talented artist’s musings on the infinite balances, imbalances, complements and contradictions that comprise the ‘human condition.’” Nakamura’s work will only become more relevant as people continue to move and mix among each other. Rather than think of this hybridization as a loss or confusion of culture, we can look at it the way we look at Joel Nakamura’s artwork: as a beautiful, imaginative, and blended representation of what was, what is, and what could be.

* This article was originally written for the Japanese American National Museum Store Online. Custom art pieces and other items by Joel Nakamura are available for sale through the Museum Store. (June 2010)

© 2010 Mia Nakaji Monnier