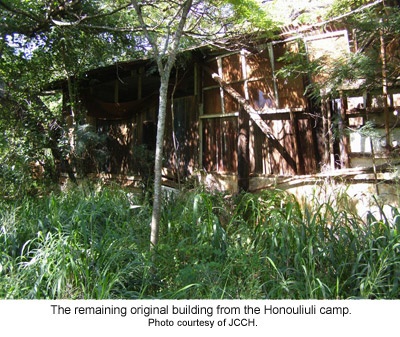

“We’ve got to find a way to preserve that,” Jeff said to me. “You know that’s an original building.”

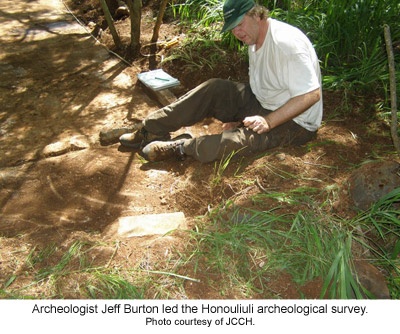

Jeff was Jeff Burton, an archeologist who works for the National Park Service and who is the recognized expert on the archeology of the sites where Japanese Americans and others were confined during World War II. It was late February, and we were on the site of the Honouliuli internment camp in central O‘ahu where Burton and his team were conducting an archeological survey.

The journey that brought Burton and company to Honouliuli was a long one that had started some ten years before. In 1998, a local TV station called the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i (JCCH) and asked about the location of the Honouliuli site in preparation for showing the movie Schindler’s List. The inquiry was referred to the JCCH Resource Center, where the all-volunteer staff conducted research to find that no one seemed to know where the camp was located. Shocked by this state of affairs, Resource Center volunteers set about to learn more about this seemingly forgotten slice of history and to make it better known to the people of Hawai‘i and beyond.

Led by co-managers Jane Kurahara and Betsy Young, the all-volunteer team made remarkable inroads. Both retired public school librarians and teachers, the pair made an ideal team. Kurahara, a career librarian, is highly organized, detail oriented, and thoroughly prepared; Young, who split her career between teaching and librarianship, is bubbly, energetic, and personable. (One staff member gave her the nickname “Forever” as in Betsy “Forever” Young.) Both are intense and driven in that uniquely nice-Nisei/Sansei-woman way. They drew on their state Department of Education contacts and powers of persuasion to build a remarkable team of volunteers with varied backgrounds and interests.

The group sought manuscript collections tied to the story of Hawai‘i internees and immediately brought in several important ones. They received funding from the state humanities council to catalogue one of them, the papers of Big Island internee Otokichi Ozaki. A unlikely coalition of local Nisei with Japanese language abilities and postwar immigrants from Japan with no prior knowledge about internment worked together to translate many of these documents into English and eventually translated two full length first person accounts of Hawai‘i internees, Yasutaro Soga’s Tessaku Seikatsu and Kumaji Furuya’s Haisho Ten Ten. The former, whose lead translater was Kihei Hirai, was published late last year under the title Life Behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai‘i Issei by the University of Hawai‘i Press, while the latter, translated by Tatsumi Hayashi, will be published in the next couple of years. Bilingual volunteers also conducted 23 oral history interviews with former Hawai‘i internees and their family members.

In 2004, the group mounted a work-in-progress display titled Dark Clouds Over Paradise: The Hawai‘i Internees’ Story and later got further state humanities council funding to travel the exhibit throughout the state starting in late 2006. The group also held an internment workshop for school teachers and librarians and later produced a portfolio of primary source material on internment that was distributed to all the public high schools in the state in response to new guidelines that mandated the teaching of the Hawai‘i internment story to 9th and 10th graders.

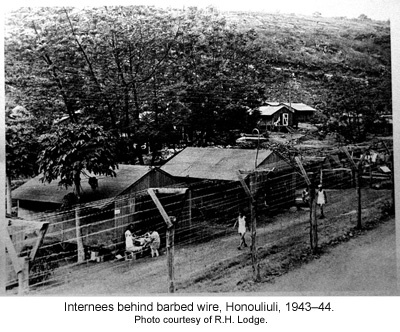

And then there were the efforts to find the locations of the camps in Hawai‘i. In the immediate aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, several hundred local Japanese—mostly Issei male community leaders—were rounded up. Initially kept in local prisons and temporary holding centers, the internees were eventually brought to the Sand Island camp located on an island in Honolulu Harbor. Detainees on the neighbor islands were held in centers on those islands for the first few months of the war—Kilauea Military Camp on the Big Island, Kalaheo Stockade on Kaua‘i, Haiku Camp on Maui, and perhaps a camp on Molokai as well. The majority of Hawai‘i internees were transferred to camps in the continental U.S. beginning in February of 1942; as these transfers took place, space opened up at Sand Island and neighbor island internees were brought over throughout the spring of 1942. On March 1, 1943, most of the local internees had been transferred and Sand Island shut down. Those who remained—most of whom were Nisei and/or Kibei—were transferred to the Honouliuli camp on that day. Though less than 1% of the local Japanese population suffered through internment, a stark contrast to the West Coast situation, the impact was profound, since those interned were the leaders of the local Japanese community. After the war, the vast majority returned to Hawai‘i, and their story has largely been forgotten in the wake of the well-documented changes that took place in Hawai‘i after the war.

Due to efforts by Jane, Betsy, and the Resource Center volunteers, the sites of the Sand Island, Honouliuli, Haiku, and Kilauea camps have been located, while the sites on Kaua‘i and Molokai are still somewhat up in the air. (Interviews with Kauai residents who claim to know the location of the camp have produced conflicting accounts of where the camp was located.) A 2006 visit by the National Park Service archeologist Burton guided by the Resource Center group led to the conclusion that the Honouliuli and Kilauea sites were the most intact and that Honouliuli would be a good candidate for an archeological survey. With the help of the local preservation community and other funders—the Conservation Fund, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the National Park Service—we were able to raise the money for the survey that took place last month.

Another result of the Resource Center volunteers’ efforts is me, or more accurately, my position. Having accomplished so much, but with so many things to do, the board of the Cultural Center decided to devote a full time staff position to the Resource Center. Having done similar kinds of work for both the Japanese American National Museum and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, I was well suited for the job. One of my first tasks was to oversee the production of the traveling version of the Dark Clouds exhibition. In reading through the panels, I came across a poem written by my grandfather, Shoichi “Seiha” Asami while he was interned. That was a pretty good omen. (It wasn’t such a good omen for my grandfather, who had been the managing editor of one of the major Japanese language newspapers in Honolulu prior to the war and who was among those detained on December 7. His and his family’s odyssey would end in tragedy in the Sea of Japan in 1945.)

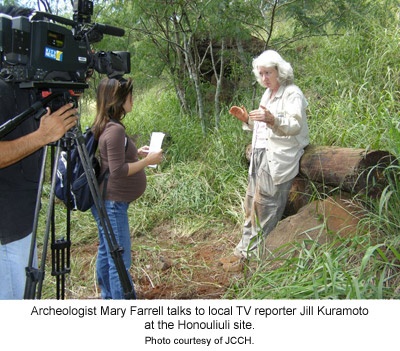

The survey took place over five days, from February 23 to 27, 2008. We had originally scheduled it for October, but rescheduled so that the archeologists might be part of the commemoration of the 65th anniversary of Honoululi’s opening that was to take place on March 2. The archeological team consisted of Burton, National Forest Service archeologist Mary Farrell (who is married to Burton), and Ronald Beckwith, all of whom flew out from Arizona, along with University of Hawai‘i archeologist Jim Bayman. We would be joined by various volunteers on the different days of the survey.

Upon meeting Jeff and Mary, I was struck by how much they were like physically larger versions of Jane and Betsy. Jeff is quiet and can seem almost dour but is friendly and has a sense of humor once you get to know him; Mary is outgoing and talkative, the person all the volunteers are immediately drawn to.

Due to the ongoing planning of the 65th anniversary events, I missed the first day, but joined the group for the second day. We met at a parking lot just outside a new residential development named Royal Kunia. There, we were greeted by representatives from Monsanto, the St. Louis-based agricultural company that owns the parcel of land the camp is located on. Since purchasing the land about a year ago, Monsanto has been vocal in their intent to cooperate with efforts to preserve the former internment camp site. At the same time, they have expressed some reservations about providing ongoing access to the site, since current access routes run through the heart of their land. It turns out that our escorts to the site are high-ranking members of their security team from St. Louis. They lead us to the site, over a mile or so of dirt roads, before hitting a paved road that leads down into the gulch.

On this day, the group is greeted with wet and muddy conditions. In contrast to how it had been in the fall, the site was now overgrown with vegetation that went over one’s head in some spots. With some difficulty, we made our way to an area that I had explored last fall. Corresponding to the administration area in historical photographs, it was an area where there were many concrete foundations along with a few objects—primarily bottles and some ceramics—that might come from the camp.

Over the course of the day, we do lots of digging and clearing of vegetation, while the archeologists measure and mark locations on maps. Though originally built to house 3,000 people, the peak population of the Honouliuli camp was only around 300. In addition to the mostly Kibei/Nisei local Japanese population, there were a few local Germans and Italians, and an undetermined number of POWs, each housed in a separate area. Over the next few days, the weather clears a bit, and the group explored the POW area of the camp along with the internee area. It is apparent that there are many concrete foundations of buildings from the camp, so many that we were literally tripping over them. Many were buried a few inches under the mud, so there was much digging and clearing to expose them so as to measure and map them. We also found extensive underground sewer systems, as well as what may have been concrete walkways in the administration area. “This is typical,” said Burton, based on his observations of the many other camp sites he has explored. “Only the administration area would have concrete walkways.”

On the last day of the survey, the group explored an area at the southern edge of the site, where there were some chicken coops that once housed birds of the fighting variety. (Cock fighting is still a popular, if illegal, pastime of many locals today.) It was in this area that Burton noticed the possible surviving building. I asked him how he could tell, and he noted the foundations and construction of the surviving building and how it matched photographs of the camp. “A surviving building is very important in a historic register nomination,” he said. (Administered by the National Park Service, the National Register of Historic Places is the “Nation’s official list of cultural resources worthy of preservation.”)

For the last three days of the survey, we were also joined by a succession of local TV news crews thanks to the efforts of Shayna Coleon, JCCH’s outstanding public relations director. (This is something else that is unique about Hawai‘i—that you get such coverage for a venture like this!) On the first day, KGMB’s Lisa Kubota braved the mud and rain and spent the whole morning with the crew, while on the last day, a very pregnant Jill Kuramoto of KITV clambered onto a raised slab to conduct interviews.

You can see their stories at:

Uncovering History at Honouliuli Internment Camp - KGMB9 News, 2/25/08

Other WWII Internment Camps in Hawaii - KGMB9 News, 2/25/08

Archaeologists explore Japanese Internment camp in Kunia - KHON2 News, 2/26/08

Volunteers Clean Oahu Internment Camp Site - KITV.com

In five days, we were able to just scratch the surface as far as documenting all the remaining foundations and other remains on the site. But based on the sample of those we uncovered—as well as on the surviving building—Burton and Farrell can write up a nomination for Honouliuli as a site “worthy of preservation.”

We’ve come a long way in ten years, but there is much more to do. A full clearing and mapping of the Honouliuli site beckon as do more extensive site surveys at Kilauea Military Camp and Kalaheo Stockade. There are also discussions to be held with Monsanto about the future of the site. The possibilities of what we may be able to do here are exciting and enticing. Stay tuned to see how this all turns out.

© 2008 Brian Niiya