“BASEBALL SAVED US”

The coming of World War II brought upheaval to the Japanese American community. On the mainland, all West Coast Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in American concentration camps. Though mostly spared such treatment in Hawai‘i, Japanese Americans there faced additional restrictions under martial law.

Setsu Okada prepared to catch a ball at Heart Mountain in front of at least one interested on-looker. Gift of Mori Shimada (92.10.2A)

In America’s concentration camps, sport served as a much needed outlet for young and old, male and female, Issei and Nisei. In some cases, teams from before the war reformed in camp to take on all comers. In other cases, new alliances and new teams were formed. Sometimes all-star teams from one camp were allowed to play similar teams from other camps. Issei were instrumental in the organization of the teams and often filled the stands, sometimes betting on the outcome of the contests. The camps also hosted sumo tournaments, basketball and football teams, and many other types of sporting activities.

Meanwhile, the Nisei men of the famed 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team and Military Intelligence Service were active in sport as well. As part of their mission to serve as ambassadors for the larger Japanese American community, they competed in a variety of sports against other military related teams and against teams from the communities in which they trained.

WHEN GIVEN THE OPPORTUNITY…

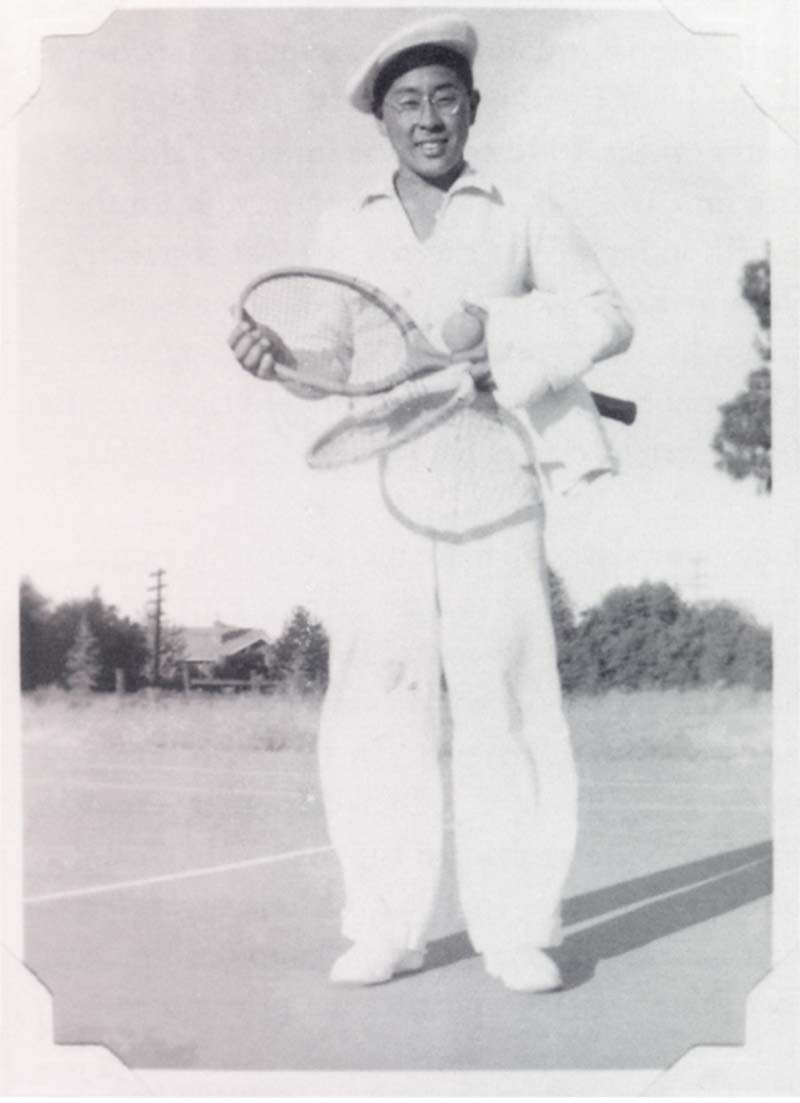

Tennis was popular among some Nisei youth prior to World War II. Fred Hoshiyama is pictured here. Gift of Emiko and Chizu Omori (94.127.123)

Japanese American athletes have risen to the highest levels of their sport when given the opportunity to compete on an equal basis. Their stories suggest that the success in mainstream sports is a function of opportunity, encouragement, and coaching. Today, as opportunities in all aspects of society open up to all, more Japanese Americans than ever are pursuing careers in sports.

The successes enjoyed by these star athletes have been avidly reported by the ethnic press and followed closely by local Japanese American communities or by the entire community. In many cases, these athletes have represented Japanese Americans to the larger population.

In three Olympic sports in particular–swimming, weightlifting, and judo–Japanese Americans have enjoyed tremendous success.

In 1937, a high school biology teacher/swim team coach from Maui named Soichi Sakamoto formed the “Three Year Swim Club.” The name came from the club’s stated goal–to make the Olympic team of 1940, three years hence. It was an audacious goal considering that Sakamoto had no prior experience coaching swimming. But against all odds, Sakamoto and his young charges became dominant performers in the world of swimming. Nisei Keo Nakama was the first of Sakamoto’s star performers, a world champion many times over who lacked Olympic medals only because the games were canceled during his prime in the 1940s. later, in the 1952 Helsinki games, Hawai‘i Nisei swimmers Ford Konno an Yoshinobu Oyakawa won gold medals and Evelyn Kawamoto won bronze medals.

Before World War II, the United States was not a major player in international Olympic style weightlifting. In the late 1940s and 1950s that changed dramatically. Bob Hoffman, publisher of Strength and Health magazine and owner of York Barbell Company, helped to put together an American team which became a world power. One of Hoffman’s secrets was to actively seek out non-WASP lifters who were often informally barred from other sports. His powerhouse teams included athletes of Eastern European, African, Latin American, and Asian ancestries. Many of the best were Japanese Americans. Kona, Hawai‘i native Harold Sakata, whose Charles Atlas-like story of the skinny kid turned muscle man by lifting homemade weights made of broomsticks, ketchup cans, and cement, became a local legend. He was the first Japanese American weight lifter to rise to international prominence, winning a silver medal at the 1948 London Olympics. Among his teammates on the 1948 team was Emerick Ishikawa, a five time U.S. National Champion who finished fourth in his weight class. Later, the legendary Tommy Kono went on to one of the greatest weightlifting careers of all time, winning three Olympic medals (two of them gold) in three different weight classes between 1952 and 1960.

Judo, a modern Japanese martial art developed from jujitsu, is said to have arrived with the first Issei in Hawai‘i. Its roots as an Olympic sport, however, can be traced to Nisei Yosh Uchida of San Jose State University. In 1953, his efforts led to the recognition of judo as a sport by the AAU; San Jose State sponsored the first AAU championships that year. In 1962, Uchida organized the first national collegiate judo championship. San Jose State won the first national title and an incredible 28 of the next 31 such college titles. In 1964, judo became an Olympic sport for the first time and Uchida coached the U.S. team. Two of the four athletes on that team were from San Jose State. One was lightweight Paul Maruyama, who later coached the 1980 and 1984 Olympic teams. The other was Ben Nighthorse Campbell, now a United States Senator from Colorado. Among the other Japanese American standouts to have passed through San Jose State are Keith Nakasone, 1978 Pan American games gold medalist and 1980 Olympic team member and Tony Okada and Sandy Atsuko Bacher, both of whom competed in the 1992 Olympics. Other Japanese American judo Olympians include Patrick Misugi Burris (1976), Steven Seck (1980), and Craig Agena (1984). The United States has never won a gold medal in judo. It came closest in 1988, when Hawai‘i native and San Jose State product Kevin Asano won the silver medal at the Seoul games.

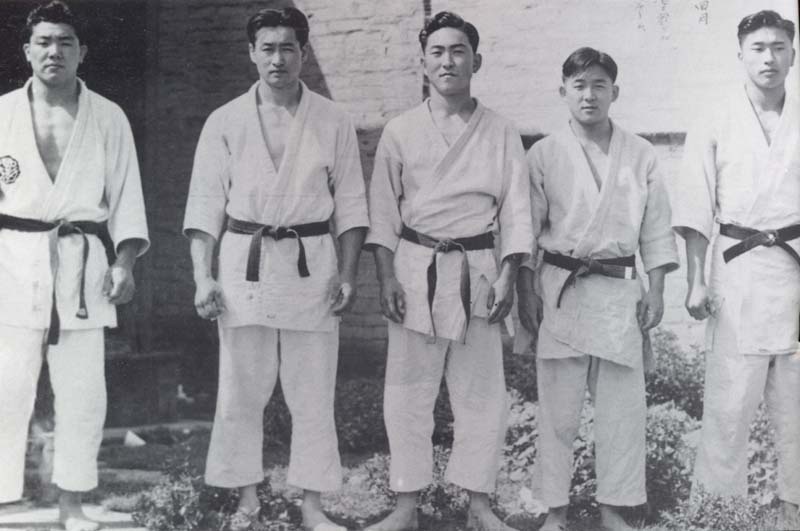

Rafu Dojo team at the Southern California Judo Tournament, April 1940. Collection of Yukio Nakamura (93.92.9)

In addition to these sports, many other Japanese Americans have participated in the Olympic games over the years in other sports. They range from fencer Peter Westbrook–one of the few ever to make five different Olympic teams–to volleyball players Eric and Liane Sato to figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi.

Another area where Japanese Americans found great success was as professional baseball players in Japan in the late 1950s and 60s. Nisei star pitcher Henry “Bozo” Wakabayashi, one of the legends of Japanese baseball in 1930s and 40s, began this phenomenon. After the war, Japanese teams looked to duplicate his success with other Nisei. For young Nisei baseball players, Japanese baseball offered an opportunity to play professionally while getting to see their parents’ home country. Many Nisei played in Japan during this period and two of them–Wakabayashi and Wally Yonemine–are in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, regarded as among the best players of all time.

Though relatively few Japanese Americans have been able to sustain professional careers as athletes, many have successfully worked behind the scenes as coaches, trainers, promoters, or in other capacities. Some, when given the opportunity, have risen to the top of their fields. Among the most notable are University of Hawai‘i baseball coach Les Murakami, the University of Hawaii’s women’s volleyball coach Dave Shoji, and California State Los Angeles basketball coach Dave Yanai.

In virtually every sport, major or minor, there have been Japanese Americans who played it very well. They include NBA basketball players Wat Misaka and Rex Walters, NFL star Johnny Morton, jockey Corey Nakatani, tennis player Ann Kiyomura, LPGA golfer Lenore Muraoka Rittenhouse, and NHL All Star Paul Kariya. Their successes blaze the trail for many who would follow them.

SPORT AND THE “PERSISTANCE OF ETHNICITY”

After over one hundred years of history and the supposed “assimilation” of third and fourth generation Japanese Americans into the mainstream of American society, segregated Japanese American sports leagues still exist in most Japanese American communities. Their segregated nature has become a source of controversy, as leagues struggle to define who can and cannot play; who is and who is not “Japanese American” or “Asian American.” While Japanese American basketball leagues contribute in no small way to the success of many high school level players of both sexes, there are voices in the community who argue that the comfort level of the leagues hurts the better players by preventing them from facing the very best competition.

Nonetheless, these sports leagues and the social networks they engender continue to be a vital part of the glue that holds Japanese American communities of today together. No longer confined to Little Tokyos, it is sport–along with churches and other voluntary organizations–that is the site of today’s Japanese American communities.

No one knows what the future holds for the Japanese American community–nor indeed if there will even be such a thing in fifty or one hundred more years. But whatever becomes of the community, it seems clear that sports will continue to play a vital role in its future.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Fall 1997.

© 1997 Japanese American National Museum