Read Part 2 >>

As a historian who has spent the better part of the last four decades researching, teaching, and doing fieldwork and writing on the World War II Japanese American story, I also find Nurse of Manzanar to possess social value in regards to how it helps to fill in the informational gaps in that important story as well as opening it up (often inadvertently through its silences) to new lines of inquiry and enhancement. So let me now spell out, briefly, the special contribution of Nurse of Manzanar to the major topics addressed within its pages: the impact of World War II on the Japanese American community of San Luis Obispo; Japanese American resettlement; the Manzanar War Relocation Center; and health care in America’s World War II concentration camps.

Because there is comparatively little written about the World War II impact upon the San Luis Obispo County Nikkei community, the importance of an autobiographical memoir such as that by Toshiko Eto Nakamura is greatly magnified in its value, since it carefully tracks the wartime experience of one very prominent Japanese American family through the eyes of a mature and perceptive member of that family.

Precisely because the overwhelming majority of the county’s Nikkei did not take the Eto family’s path of “voluntary evacuation” and then confinement at Manzanar, but rather were involuntarily remanded first to the Tulare Assembly Center in California and then to the Gila River Relocation Center in south-central Arizona, the Eto experience adds a strand of difference to the community’s dominant story.

What is conspicuously absent from Nurse of Manzanar, aside from that dominant story, is the wartime experience of Japanese Americans in San Luis Obispo who were not as well connected with the mainstream community as the Etos. Even though their good name was tarnished and erased from the signpost of a city street, the Etos did at least have custodial care for their property during the war. What about less favored families? What was their plight? This is a topical area that needs to be explored.

Also, since Toshiko Eto Nakamura’s manuscript does not cover the postwar experience of the San Luis Obispo Nikkei community, we are left in the dark as to how many Japanese Americans returned to San Luis Obispo County after the war and how many did not “return home,” the reasons for the disparity between these two groups, and whether the situation varied considerably among the county’s towns and outlying rural areas. This is still another topical area begging for research activity.

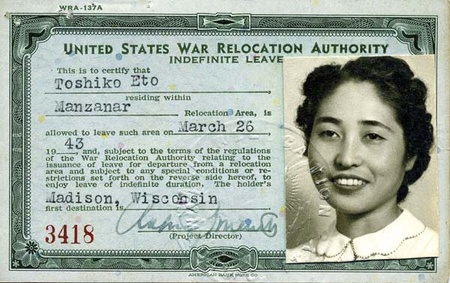

Indefinite Leave Identification Card for Toshiko Eto. (Samuel Nakamura's family files. Courtesy of Samuel Nakamura)

The last mentioned topical area, of course, also falls into the category of resettlement. The signal accomplishment of Nurse of Manzanar in this regard is to provide a nicely developed case study of “voluntary resettlement” within California that occurred in the interval between the attack on Pearl Harbor and the end of March 1942. This migration is often alluded to in published studies on the Japanese American wartime experience, but it is usually glossed over and almost always lacking in specific time-and-place information. In this category, too, what Toshiko Eto Nakamura does not talk about can and should serve as a spur to further research.

For instance, her manuscript ends with her leaving Manzanar for resettlement in Madison, Wisconsin, but she tells us virtually nothing about her living and working experience there. There has been a lot of scholarly attention paid to resettlement in relationship to Chicago, which served as a temporary or permanent home for some twenty to thirty thousand Japanese Americans during and immediately after the war. In fact, up through the mid-1950s, the “Windy City” retained enough of this population to make it Cold War America’s most prominent mainland Nikkei hub of commerce and culture outside of Los Angeles. But apart from Chicago, very little serious study has been devoted to the phenomenon of Japanese American resettlement in other Midwestern urban centers, whether of large or modest size. So resettlement in the medium-sized progressive college city of Madison, as well as in its counterpart communities throughout the Midwest, deserves much further investigation and documentation.

As for the topic of Manzanar, Toshiko Eto Nakamura contributes in her memoir a thoughtful overview of this camp’s physical and social makeup. In the latter regard, what she has to say derives from the perspective of an “outsider,” since unlike the bulk of Manzanar’s population, she and her family were not from the Los Angeles area. This perspective allows her to view the community “objectively,” to see the forest instead of the trees, to not be blinded to significant commonalities because of a myopic preoccupation with marginal variations.

But it also militates against her being aware of and commenting upon the heterogeneous character of Manzanar, such as the socio-cultural differences between those blocks comprised of Nikkei from Los Angeles’ downtown, west side, east side, and harbor areas. A topical area in which the author is silent is her social situation as a single woman in her early thirties. When she came to Manzanar, the average age of the Nisei (U.S.-born citizen offspring of immigrant Japanese Americans) population was seventeen and one-half years old, while that of Issei (immigrant generation Japanese Americans) males was fifty-five, and Issei females in the mid-to-late forties. These populations, especially the Nisei, have received a lot of attention in the literature on Manzanar. But far less has been written about “older” Nisei, particularly Nisei women in the age range from twenty-five to forty, and this situation needs to be redressed.

Toshiko Eto Nakamura is also silent about Manzanar’s Kibei population, which is unfortunate, since even though she did not receive her formative education in Japan, the standard defining characteristic of the Kibei, she did live in Japan between the ages of four and eleven and therefore was in a position to understand and empathize with this Nisei subgroup. What has been written to date about the Kibei at Manzanar has chiefly focused on them as pro-Japan troublemakers, most especially in connection with the Manzanar Riot. This research topic still cries out for a broader and more objective assessment.

Toshiko Eto Nakamura was not an eye-witness to the Manzanar Riot on the evening of December 6, 1942, but she did witness its afternoon build-up and its after-effects at the Manzanar Hospital when she reported for duty later that same night. Her observations in this regard are significant and trustworthy. So too is her account of the just-after-midnight removal to safety from the hospital of the Nisei JACL leader whose December 5, 1942, beating set in motion the chain of events leading to the Manzanar Riot, and also the subsequent hospitalization (two days after the Riot) and agonizing death (on Christmas Eve) of this man’s mother. On the other hand, the evaluation of the Manzanar Riot’s causation offered in Nurse of Manzanar is patently derivative and adheres too closely to the perspective of the U.S. government, the WRA camp administration, and the JACL. This explanation needs to be supplemented by assessments drawn from other perspectives, as well as the development of fresh approaches to conceptualizing the Riot’s long-range causes.

Because Toshiko Eto Nakamura was a very well educated, trained, and abundantly experienced registered nurse, the substantial section of her memoir dealing with medical care at Manzanar indisputably represents her most important contribution to the literature on the World War II Japanese American experience. In addition to providing a structural and experiential description of the exceedingly small and quite primitive original hospital that served the Manzanar population from its opening in late March 1942 and the impressive 250-bed hospital that supplanted it in September of that year, she discusses the hospital leadership and staff, and surveys the diverse types of patients treated at the Manzanar Hospital.

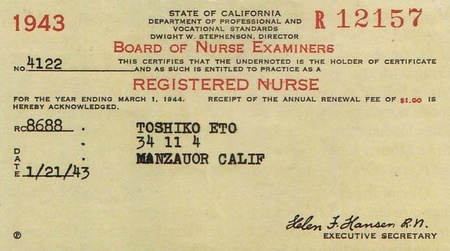

Toshiko Eto's 1943 Nurse's License, addressed to her at MANZAUOR [sic] CALIF. (Samuel Nakamura's family files. Courtesy of Samuel Nakamura)

Perhaps the most fascinating portion of her discussion in this respect, however, is in relationship to a class of patients not treated at Manzanar. “There were a few mental patients,” she writes, “but I am sorry to say the hospital was ill equipped to properly deal with them.” The extent of such patients and how they were dealt with, or not, at Manzanar and the other WRA camps is but another topic that deserves further research.

One additional topic that falls into this category is the type of medicine practiced in the WRA camps, whose populations were compounded of those who were accustomed to and comfortable with traditional Japanese therapeutics and those who preferred Western scientific medicine. It would have been interesting and fruitful had this general topic been probed by Toshiko Eto Nakamura relative to Manzanar, since her childhood experience in Japan and her coming of age in the pre-World War II agricultural county of San Luis Obispo, California, likely familiarized her with traditional therapeutics, while her nursing education at the Stanford University School of Nursing in San Francisco, California, and her 1937-1942 professional work experience at the San Luis Obispo Sanitarium and the Mountain View Hospital in San Luis Obispo would necessarily have schooled her in the theory and practice of Western medicine.

Clearly, the aesthetic value of Toshiko Eto Nakamura’s memoir is matched by its social value. Through silently bequeathing to potential readers her moving post-World War II reflections of her and her family’s wartime ordeal, she has simultaneously laid her claim on posterity as a writer and issued a palpable reminder to us all that the price of liberty is indeed constant vigilance.

* * * * *

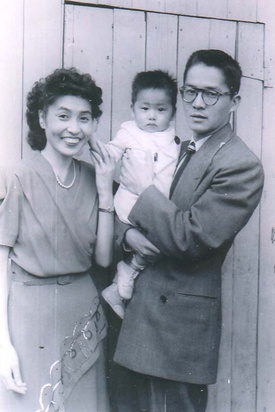

Colburn and Toshi Nakamura with their son, Sam, circa 1948. (Samuel Nakamura's family files. Courtesy of Samuel Nakamura)

One greatly overused contemporary buzz word is “value-added.” However irritating it is to encounter this word in the print and electronic media or at business meetings and social gatherings, it nonetheless encapsulates for me the nature of the editorial contribution that Samuel Nakamura has made to the original memoir, “My Memories of World War II,” written by his late mother Toshiko Eto Nakamura.

He not only has provided this manuscript with a new and more suitable title, Nurse of Manzanar: A Japanese American’s World War II Journey, but also invested it with an assortment of features that collectively ease the experience of reading it and greatly enrich its value as a historical document. In addition to writing a Preface, an Introduction, and an Epilogue for the volume, he has organized the memoir into discrete and appropriately titled chapters, developed a Bibliography and an Index, adorned the text with a rich variety of judiciously selected and useful illustrations, and assembled an assortment of Appendices consisting of primary-source documents relating to the World War II experience of his mother and the Eto and Nakamura families.

As fine a memoir as “My Memories of World War II” is, Nurse of Manzanar takes it to a considerably higher level of excellence and significance. Sam’s mother could not have asked for a better editor, a more conscientious historian, or a greater gift from a loving son.

* This article was originally published as the Foreword for Nurse of Manzanar: A Japanese American’s World War II Journey by Samuel Nakamura in 2009.

© 2009 Art Hansen