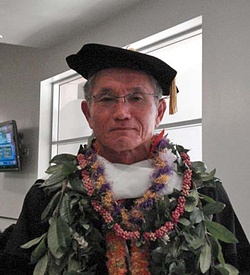

On December 2011, veteran Okinawa broadcaster Shinichi Maehara was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa—he was the first Okinawan to receive the degree.

During his career, Maehara visited Hawai‘i many times to interview Hawai‘i Uchinanchu for his documentary series, “Sekai no Uchinanchu” (“Worldwide Okinawans”), which he produced from 1987 to 2004. The degree noted Maehara’s contributions to the understanding of Okinawans worldwide.

Maehara also took time during his visit to run in the Honolulu Marathon and to share his insights on Okinawans worldwide in a talk at UH, the text of which we share with you. Maehara-san delivered his talk in Japanese—his comments were translated by Michael Lintaro McDermott.

* * *

Shinichi Maehara was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa in December 2011.

Until June of 2011, I worked for OTV, the Okinawa Television Broadcasting Company, a local station, for 38 years. I spent most of those 38 years at the forefront of production and reporting. For 17 years, between 1987 and 2004, I worked as the production director for a documentary series titled “Sekai no Uchinanchu” about Okinawan communities and immigrants overseas.

During the run of the series, we traveled to 35 countries and interviewed approximately 500 Okinawan immigrants. The total coverage distance tallied 480,000 km., or about 12 times around the globe, from which we created 210 30-minute documentaries. In 2003, following the Okinawa broadcasts, we began airing the programs in Hawai‘i on the Nippon Golden Network.

I would like to talk about why so many people migrated overseas from the southernmost and smallest prefecture of Japan; the background behind how the Okinawan people, known as Uchinanchu, were able to maintain their Okinawan spirit and mentality overseas and why they were able to strengthen their overall identity.

First, I would like to explain the word Uchinanchu, which, in Okinawan language, refers to the Okinawan people. The phrases “Okinawan” and “Okinawan people” were previously used in the mainstream, but since the media and colleges have recently been adopting the word, I will use “Uchinanchu.”

The migration of Okinawans began in the year 1900, when 26 Uchinanchu arrived here in Hawai‘i. Although there were other smaller migrations to the mainland U.S., this was the first large-scale effort. Over the next decade, Okinawans settled on the U.S. mainland, in Canada, Mexico, Cuba, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, the Philippines, and New Caledonia.

According to the overseas immigration statistics for 1940—the year the Pacific War began—there were 57,000 emigrants from Okinawa, which was third after Hiroshima’s 72,000 and Kumamoto’s 65,000.

However, when looking at the rate of emigration compared to their population, Okinawa was first with 9.9 percent, Kumamoto was second with 4.7 percent and Hiroshima was third with 3.8 percent, which shows that Okinawan emigrants were outstanding in number. Okinawa’s population was approximately 600,000 at the time, which means one in 10 Uchinanchu had gone overseas.

Why so many emigrants from Okinawa? From the 14th to the 19th centuries, the Ryūkyū Kingdom had developed its own culture, separate from both China and Japan. However, the kingdom was overthrown during the Meiji Restoration and became the Ryūkyū Han, and then in 1879, a prefecture under Japanese jurisdiction.

During the early 20th century, aside from farming, Okinawa had very few industries and was a slow-developing economic region. With its large population and limited land, the people suffered from poverty. It was during these times that an immigration firm began recruiting people for overseas work opportunities, and many Uchinanchu bought into the idea.

There was a special Uchināguchi (Okinawan language) phrase that many families used as they sent off their emigrants: “When you get there, send the money first. The letter can wait.” This is how poor Okinawa was at the time—the families waited anxiously for the money they desperately needed.

But life for the overseas pioneers was also harsh beyond imagination. The first Uchinanchu immigrants who arrived in Hawai‘i were sent to a plantation on the ‘Ewa side of O‘ahu, west of Honolulu. The hoe hana (weeding), kachiken (mowing), and happaiko (carrying) work in the sugar fields must have been tough.

The first emigrants from Okinawa arrived in Peru in 1906. Thirty-six Uchinanchu worked at a cotton farm in the village of Santa Clara, located some 450 km. from the capital city, Lima. The owners were Spanish and they slept in rundown dirt shacks called adobe and worked 12-hour shifts.

Twenty years ago, I interviewed 92-year-old Ushi Kureya, who had worked on the farm. Of the working conditions, Kureya told me in Uchināguchi, “I thought I had come all the way to Peru to die.”

The first 325 immigrants from Okinawa arrived in Brazil in 1908 aboard the immigrant ship, Kasatomaru. They all worked as contracted hands at a coffee farm. That year’s crop was poor, however, and nobody made the money they had hoped to earn. Having been told by the recruiters that there was a “money-making tree called coffee” in Brazil, it was a great disappointment.

Many in the first wave of Okinawan emigrants who had intended to earn a living overseas were hit with the reality of very little money for all their hard work. In order to find jobs that paid more, they gave up farming and began moving into the cities: In Hawai‘i, to Honolulu. In Brazil, to Santos and Sao Paulo. In Peru, to Lima and Callao. From Brazil to Argentina. Over the Andes, from Peru to Bolivia. Across the border from Mexico to Los Angeles. The first Okinawan immigrants kept migrating.

This was very different from immigrants from other regions of Japan. The Okinawan immigrants in Hawai‘i were called “Achi-kochi men,” or “here and there people,” and were perceived by those from other prefectures as having no patience. In Brazil, many ran away from farms midway through their contract and were viewed by some Japanese as “escapist immigrants” and troublemakers.

Why, in comparison to the other immigrant groups, did so many Okinawan immigrants move away? It was probably because the people felt it was most important to send money to their families back home.

Having left Okinawa with the words, “send the money first” in their heads, the Okinawan immigrants tended to continue moving in search of better opportunities to make money whereas Japanese immigrants patiently endured the hardships and remained in one place.

*Mr. Maehara’s speech in English was originally published in the Hawaii Herald on August 17, 2012. Republished on Discover Nikkei with permission.

© 2012 Hawaii Herald; Shinichi Maehara