Last week, Patricia Wakida wrote a profile on translator Andrew Leong on his upcoming book, Lament in the Night, a collection of two novellas by previously forgotten Issei writer, Nagahara Shoson. She also had an opportunity to join Kaya Press staff to interview Andrew about the project. Here is an excerpt from that conversation.

Kaya Press (KP): Why did you decide to start this project?

Andrew Leong (AL): It started out as a language-learning exercise. Very early on, when I just had a basic proficiency in Japanese, it was a way of teaching myself more about the language, but as I started learning more and went to Japan, I started looking back at this novel in relationship to other kinds of issei novels and thought there were a few interesting things about the work. One, it can be read as a corrective to other issei works written in English around the same time. So writings by Yone Noguchi (The American Diary of a Japanese Schoolgirl) or Etsu Sugimoto (Daughter of a Samurai), were written by or about people of higher class backgrounds, and were designed to impress upon the American public how sophisticated the Japanese were. The point was to create an image of urbane, cosmopolitan protagonists.

I think Nagahara’s writing is interesting because it’s more about the gritty realities of migrant life, the kinds of dirty laundry that you wouldn’t want to have aired to the general public. Things like adultery, problems resulting from the Exclusion Act, problems related to age gaps in marriage for younger Japanese women who migrated to marry older Japanese men, gambling, and prostitution. Also, you could say that within Asian American studies, there’s been some neglect of literature written in Asian languages from before WWII. I think it’s important to remember that Asian American literature didn’t start with figures like Hisaye Yamamoto or Toshio Mori, but has a much longer history dating back to when migrants first landed in the US.

KP: Have you been reading other issei novels? How does Nagahara stand out?

AL: Other writers who were within the iminchi bungei (migrant land literature) movement were calling for more realistic and naturalistic portrayals of Japanese life in the United States, but often under the assumption that the plot lines would be more rags-to-riches, Horatio-Alger-type stories about people overcoming adversities. Even if characters engaged in things like gambling or prostitution, the major arc of the stories was geared more towards redemption. Another style of novel at the time was written by people who returned to Japan, which emphasized the wretched and abject nature of the Japanese migrants as these debased, primitive, back-country people who had come to the United States and descended into poverty or vice.

Nagahara’s novels tread a line between these two kinds of works. There’s an attempt to look at how, even after all these horrible things happen to the protagonist, there’s still a bare remainder that survives. These novels are not necessarily about material success, but more about what spiritual, metaphysical remainder that still exists even after all material possessions have been stripped away. When all these horrible things happen to Osato, for instance, she still finds some way to keep on living. In other kinds of novels, she may have committed suicide, but I was interested in how Nagahara depicts this bare element—this minimal condition for survival—in a way other novelists never really reached.

KP: Why do you think it’s important for readers to look at Nagahara’s work? What do you think they could learn about the literature and culture of this time period?

AL: The scope of his psychological insight into his central characters is something I really admire. With Osato, it’s interesting how he is also able to switch the central conventions of the issei woman as a passive victim, as in the helpless picture bride stereotype. This makes her a protagonist that I think is well worth readers’ time and interest.

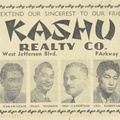

His novels also have really rich descriptions of Los Angeles in the 1920s. You can look at vintage photographs or newspapers or advertisements, but the thing about a novel—a well-written novel—is that it can really bring you in to what it feels like to live or experience an entirely different world. If you are interested in noir or early Los Angeles history because of movies like Chinatown, this is a novel written as if all the domestics in Faye Dunaway’s house are talking about their experiences as gardeners—people on the margins of great early Hollywood depictions of Los Angeles. People like to imagine the past as being a lot more glamorous or exotic than it might have been, so another valuable aspect of this novel for readers interested in this time period is that it is current to that period instead of a retrospective reconstruction.

KP: Can you describe the kinds of effort you made to track him down?

AL: Thankfully, the original text of Lament in the Night has copyright and printing information on the back that lists Nagahara’s real name—Nagahara Hideaki. So I went through immigration records at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) to track him down. I also went to ancestry.com, looked at census records and did research at the Center for Japanese Overseas Migration Museum in Yokohama, Japan. I discovered the Tale of Osato just by flipping through pages of the Rafu Shimpo , looking for any information about Nagahara Shoson and his work. It was really a lucky thing to stumble upon.

Looking at his immigration records, I was able to find out only very basic information—like where he was born. I boarded a one-man train to go to his hometown, Yama-no-Uchi [in Hiroshima prefecture] but finding records for Nagahara Shoson was also quite difficult. My hope is that in the publication of this novel and spreading the word about it, someone who knows more about the history of Nagahara Shoson as a person or an author—someone from his family—will be able to fill in more about his past, which I imagine is quite rich and interesting in its own right. The irony is that we know so much more about the characters he told stories about than we know about the life of Nagahara Shoson himself.

KP: What were the most challenging aspects of this particular translation?

AL: One issue was trying to figure out tone and style, especially in the Tale of Osato . I found that the most difficult to translate because Nagahara Shoson really shifts between a large range of different styles and modes and figuring out ways to render those in English was quite challenging. At one point, two characters in the tale of Osato are talking in the car and one says, “but we’re both no-sabe,” which is a Spanish phrase for “don’t know” that’s been translated into slang for “know-nothings,” or “we’re both stupid, we didn’t make anything of ourselves.” In some sense Nagahara Shoson was also a translator. He was translating English conversations into Japanese, but not quite standard Japanese—a language more strongly influenced by American English, with traces of Spanish and Cantonese in it, too.

* * * * *

BOOKS & CONVERSATIONS

Lament in the Night by Shoson Nagahara

Saturday, February 23, 2013 • 2PM

Japanese American National Museum

Los Angeles, California

Purchase the book from the Museum Store >>

© 2013 Patricia Wakida