“I’ve never felt myself to be a member of a minority in Cuba. We’re Cubans!”

—Nisei Francisco Miyasaka

Although Cuban Nikkei represent a small group, about 1,200 in a country of 11 million, I was immediately intrigued when I got news from Gerry Hewson that a “Cuban Japanese” friend of her and husband George’s was going to give a talk at the Toronto JCCC.

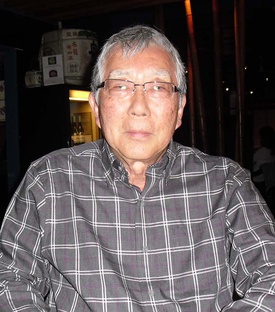

As I know very little about the Japanese who immigrated to South America and nothing about the Cuban Japanese in particular, I was immediately taken by this chance to interview the amiable Francisco Shinichi Miyasaka, 75.

The timeframe for immigration from Japan shares certain commonalities that coincide with the opening up of Japan with the invasion of US Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794-1858) in 1854 and the Meiji Era (1868-1912). The first Japanese immigrant to Cuba was an “Osuna” who arrived via Mexico in 1898 along with six others. Little else is known about him.

The first Japanese immigrants to Cuba worked as sugar cane farmers, miners, and fishermen. As a community, they were known for their dedication, industriousness, and discipline.

Francisco Miyasaka’s father Kanji migrated to Cuba from Nagano-ken in 1924. Following World War One there was a great world-wide demand for sugar and workers came from South American and Caribbean countries as well as Japan. His uncle, Tohji Sezai, who stayed and died in Cuba at an old age, arrived first. His father, Kanji Miyasaka, is from the then-named Koushoku, now Chikuma, close to the river of the same name. He married Kesano (nee Machida) from Shinonoi City, which is one railway station before Nagano-shi. That city is close to Kawanakajima, the site of a famous battle during feudal times.

The best sugar cane cutters were the African slaves and their descendants. Despite there already being millions of natives living in Central and South America, black people were most suited for this work due to their physical strength.

I was born in October 1938, says Francisco, who is visiting Toronto to see his daughter, Miharu, who recently completed a PhD at Western in London, Ontario.

“My father was one of the founders of the ‘Renrakukai’ for the Japanese Cuban association. Before passing away he asked me to try to continue it. I thought that that was for the old people. Older people always want to keep these connections.” The Nikkei community living on the Island of Youth (close to 200 persons strong), have held Obon celebrations there every year around August 15th for many years.

Some Japanese immigrants and their descendants used to gather once a year in Havana at a Chinese restaurant. Since the building of the pantheon of the Japanese Colony in the Havana cemetery in 1964, they have met there on the second Sunday of every November.

“No, we didn’t have O-shogatsu (Japanese New Year). It was difficult to get mochi, make ozoni, kamaboko. Mother used to make miso using chick peas, not soya beans; tsukemono was easy to make. In the city, people would object to the smell but in the countryside it was no problem.” (Today, some hotels have “Asian” food which may include, sushi, but it is very expensive and no good. In all cases, it has been brought in from Peru, he points out.)

“There was no maguro (tuna) but I remember in Havana, father sometimes went to market to get marlin for sashimi. We could also get tofu, wakame, and kombu in Chinatown. There was no nori or nihonshu.”

The Japanese housewives preserved Japanese culture and language, teaching children the language and improvised to make Japanese-like food even when the genuine ingredients weren’t available. Similarly, these connections often disappeared when the Japanese father was married to a non-Japanese.

During my first five years, Francisco recalls, “I spoke mostly Japanese. Father spoke Spanish well enough to be an interpreter for the sports ministry. Mother’s was not so good.”

The family lived a quiet life on the estate of the American owned Stewart Sugar Mill, where his father worked as a gardener up to the time when he was taken to a concentration camp during World War Two. After his return home in early 1946, the family moved to Havana City where his father got work as a gardener on the estate of a rich Cuban.

“Well I haven’t any special reminiscences of my childhood life at the estate and village of my birth, with the exception of the vivid image of my father being taken away from our home flanked by two soldiers to the concentration camp located hundreds of miles away (this is the only image I have kept clearly in my mind about these years),” he recalls.

The absence of neighbours during his life on the estate meant that he had close contact with his mother up to his enrolment in the village’s public school. “This benefitted me in case of the Japanese language over other Nisei living in the cities or with many Cuban neighbours around. During all those years, up to their passing, I never spoke in Spanish with my parents, only Japanese,” says Francisco who has no formal English schooling.

“On the other hand, my life in the village wasn’t any different from the life of the other Cuban children and, if anything, it could be pointed out that when I was six years old, I became acquainted with baseball at my primary school, which has been the sport I most love during my whole life.”

© 2013 Norm Ibuki