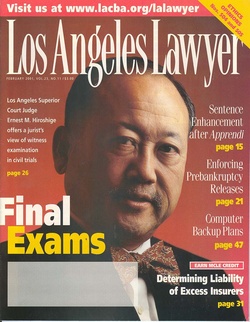

Anyone who has ever met Judge Ernest Hiroshige, who sits on the Los Angeles County Superior Court bench, knows about his signature bow tie. There’s no huge story behind it—“I just like bow ties,” he said.

The influence of his bow tie reaches far beyond the walls of Department 54 at the Stanley Mosk Courthouse. In fact, the 32-year-old veteran of the bench tells a story about Clyde Kusatsu, a friend and actor who wore a bow tie—in honor of Hiroshige—to an audition for the role of a judge on the legal drama L.A. Law. (Kusatsu got the part.)

Far more wide-reaching than his trademark bow tie is Hiroshige’s legacy as a pioneering jurist in the Japanese American community. His is a story that begins in 1945.

The Camp Experience

Hiroshige was born on August 13, 1945, in the Rohwer, Arkansas, War Relocation Center, one of the inland concentration camps that housed displaced Japanese Americans during World War II. Though he was not old enough to remember it, the concentration camp experience would certainly make an impression on him later in life.

“You can’t help or avoid understanding where you were born and why you were born there,” Hiroshige said. “Although I never experienced it [the camp experience] myself, being just a baby..., you do have this feeling about the camps that you were born there. You always wonder, why do I have this strange birth spot, birthplace, of Rohwer, Arkansas, and I’m an Asian Pacific, you know, so it’s...kind of odd.”

In his sophomore year at UCLA, Hiroshige researched the wartime incarceration of West Coast Japanese Americans for a paper in a U.S. history class. The experience was eye-opening.

“A lot of it [the mass incarceration] had to do with a lack of legal representation for Japanese Americans and the lack of Japanese American lawyers also,” Hiroshige said, recalling some of the conclusions he drew from his research into why the incarceration happened. The process of researching the camps also led him to interview his parents, who until then had not revealed much about the Rohwer War Relocation Center.

“Everyone in the Japanese American community as I saw it growing up was…the impression I got was that everybody was having fun and it was a good experience being at the camps, you know. But I think most of them were…they’re hesitant to talk bad about the government,” Hiroshige said. “That was the first time my mother and father would really look at it—the camp experience—and say, ‘Yeah, we were there because of discrimination against us.’”

In law school, Hiroshige remembers a heated discussion in a constitutional rights class in which the professor discussed the legal cases and decisions dealing with the mass removal of Japanese Americans into concentration camps during World War II.

He remembers one classmate who “challenged the professor after he [the professor] discussed these cases and how wrong they were. He said, ‘Would you feel the same way if the Japs would have won?’” But he also remembers speaking up and relying on his depth of research into the topic to make the case that the concentration camps were certainly wrong and unjust.

Learning about the camps “has always influenced my behavior as a deputy DA and as a judge,” Hiroshige said, insofar as it has made him acutely aware of any potential marginalization or discrimination against someone or a group of people, according to Hiroshige.

“I feel responsibility to be always aware and vigilant that someone else’s rights are being trampled in the courts or in society, so I’ve always had that in my mind as a duty to be fair as a judge,” he said. “So I feel that’s a nice part about our job [as judges]. We have opportunities—not every day, but once in while—you see a case where some people are being very unfairly treated and people are getting away with it so they’re in a courtroom, and justice can be done.”

The District Attorney’s Office

After graduating from the UC Hastings College of the Law, Hiroshige became a deputy district attorney with the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office, where he spent six years handling criminal matters, including fairly major rape and murder cases.

“Criminal [law] was always exciting, but I sort of tired of all the blood and guts,” Hiroshige said. “If you get somebody who’s serious off the streets for a serious crime, you feel you’ve done your duty. But on the other hand, it’s just one continuous bad crime after another, unfortunately, so it’s sort of like a negative overall feeling I felt in criminal.”

Eventually Hiroshige opted to enter the special unit on consumer protection in the district attorney’s office, where he filed civil lawsuits for false advertising and labor law violations against companies. Highlighting some of the differences between practicing criminal and civil law, he mentioned that civil law offered intellectual rigor even as it avoided some of the less appealing aspects of criminal law.

“[With civil law] nobody gets the death penalty and nobody goes to jail as a result. Somebody gets more money or they lose money. That’s about it.”

Generally, Hiroshige appreciates his time at the district attorney’s office.

The “[district attorney’s] office gave me the opportunity to experiment in...trial technique,” among other things, according to Hiroshige, who explained that as an early prosecutor, he was able to acquire effective courtroom techniques as a trial lawyer for several years.

Japanese American Bar Association

One of the founding members of the Japanese American Bar Association, Hiroshige served as the organization’s second president in 1978, after the first founding president, Edward Kakita. Justice Kathryn Doi Todd had been slated to become president in 1978. When she was appointed to the Municipal Court before she could take office, Hiroshige stepped into the presidency.

Speaking to the founding of JABA in the 1970s, Hiroshige explained that the organization emerged in large part from the sociohistorical context of the times.

“It was a time where minorities were getting more aggressive and asserting their rights and being proud to be minorities, and so certainly our bar represents one of the older, traditional areas of Los Angeles—Little Tokyo,” Hiroshige said. “And I thought it [JABA] was a great idea.”

Lauding the stronger connections forged between Japanese American lawyers and also the bridges built across communities, Hiroshige spoke to the bold strides that JABA took in the 1970s, and the accompanying benefits of being involved with it.

The presence of JABA and other Asian Pacific American bar associations “got us closer together, really, because through these bar activities, we got to know each other better,” Hiroshige said, emphasizing the much-needed networks that JABA helped construct.

Furthermore, JABA took an active role in a coalition with other minority bar associations to discuss increasing minority representation on the bench and strengthening the voices of minorities within the L.A. County Bar Association. The coalition, called the Minority Bar Association, no longer exists. It included the John M. Langston Bar Association, the Black Women Lawyers Association, the Mexican American Bar Association, and all the Asian Pacific American bar associations, according to Hiroshige. As secretary of the Minority Bar Association in 1978, Hiroshige remembers the lawyers he came to know better and also the mutual assistance these organizations expressed for one another.

“We sort of all mutually helped each other,” Hiroshige said.

Apart from its participation with various other organizations in the legal community, JABA not only revitalized an interest in supporting Little Tokyo’s legal needs through community-oriented legal clinics but also integrated its own leaders into the local community, according to Hiroshige.

The formation of JABA and its active engagement with the Little Tokyo community effectively “reintroduced some of the lawyers to the JA [Japanese American] community,” according to Hiroshige.

Hiroshige added that some of the challenges that JABA might face in the near future includes keeping its membership up and maintaining an interest in supporting Little Tokyo and the Japanese American community.

“It’s amazing that there are still a lot of Japanese American lawyers that still consider themselves Japanese Americans. And they’re young lawyers, so I find that very encouraging,” Hiroshige said, citing the fact that JABA boasted its largest membership ever this past year.

Making The Bench

When Governor Jerry Brown’s judicial appointments secretary, J. Anthony Kline, reached out to various minority legal communities in a push to diversify the bench, Hiroshige had been planning to turn to the private sector to practice civil law. When he was approached to put in an application for a judgeship, though, he decided to apply.

“People thought I was fair and tried to resolve cases,” Hiroshige said, emphasizing the importance of judicial temperament and fairness in the evaluation process. He also recalled getting positive reviews from opposing counsel, which he believes were instrumental in his judgeship.

Even before the official phone call from Kline, though, Hiroshige received hints of good news.

“The rumor mill hit you first. They said, ‘You’re going to get it,’” Hiroshige said, recalling how he found out that he had been appointed from the people around him who had heard.

“I thought it was all amazing,” Hiroshige said. “I was lucky.”

Thinking back on his elevation to the Superior Court in 1982, two years after he became a Municipal Court judge, Hiroshige attributes it to a combination of hard work and good fortune.

“I tried to do the best I could as a judge, and hopefully you’re going to get some community support for it, and I was elevated two years later,” he said.

Hiroshige has presided over an unlimited civil courtroom for 23 years, and every day is still as interesting as the first.

“I still find it interesting to work, and it’s pleasant,” Hiroshige said. “I get up every morning, and I feel, you know, it’s going to be interesting today. It’s been a nice career, because I always look forward to meeting whatever the challenge [is] that day.”

Staying Involved in the Community

When he is not in the courtroom, Hiroshige enjoys all things theater-related. A former child actor, Hiroshige had small roles in films like The King and I with Yul Brynner and in Tea House of the August Moon with Marlon Brando. His love of the theater has not abated. Hiroshige has been on the board of directors of the Center Theatre Group, and he currently chairs the Asian Pacific American Friends of the Theater (APAFT), an organization dedicated to the development of Asian Pacific American artists, actors, writers, directors, and producers.

“A lot of people ask me, ‘Why are you involved in this? What’s a judge doing even being involved?’” Hiroshige said. “I have to explain, I do have this background. It’s something that I experienced. And I have a lot of empathy for actors and what they go through, and directors, and the whole dramatic art.”

In discussing APAFT’s goal of encouraging the development of Asian Pacific American dramatic artists, Hiroshige commented on the personal significance of helping get Asian Pacific Americans artists into the mainstream.

“When we’re cast to be Americans in an American play, then it does a lot to enhance the image of Asian Pacifics, in my mind,” Hiroshige said.

Admitting that encouraging Asian Pacific American artists might not be the largest, most urgent issue in the community, Hiroshige maintained that it is an “overall positive issue” that can help push underrepresented groups to the most visible levels of mainstream theater.

“After all, there are even judges who are Asian Pacifics, right?” Hiroshige said, chuckling.

In addition to the theater, Hiroshige remains actively involved as the chair of the board and founding president of the Asian Pacific Alumni of UCLA.

It’s a vehicle to have more networking among Asian Pacific alumni and then outreaching back to the students, and also to have more of a voice in the future of UCLA, and the governance of UCLA,” Hiroshige said. “Asian Pacifics don’t have anywhere near what their influence should be at UCLA, but we’re working on it.”

“My personal involvement is more in the Asian Pacific community, which includes the Japanese American community,” Hiroshige said, stressing the need for the distinct ethnic groups to come together and generate collective power as Asian Pacific Americans. “To me, I think you need to build bridges between communities for the future.”

Hiroshige’s involvement with these community organizations, as well as various Asian Pacific American bar associations, symbolizes his strong support of people in the community. In fact, in 2011, Hiroshige received the Public Service Award from JABA.

“I want to be supportive of the Asian Pacific attorneys, and have a dialogue about what’s going on on the bench versus what’s going on in the practice,” Hiroshige said. “And they should feel that they have access, that they can talk to a judge, on general terms.”

© 2012 Lawrence Lan