Read part 5 >>

But there is still more to the Masuda family story.

In 1948 when Kazuo’s remains had been disinterred from his grave in Italy and shipped to the United States for reburial in his native Orange County, the family had a rude surprise when they met with the manager of the Westminster Memorial Cemetery to make burial arrangements. He informed the family that the cemetery was a racially restricted one, and this meant that Sergeant Kazuo Masuda could not be buried in a desirable spot within the cemetery (desirable meaning a central location with trees and a lawn).

This revelation, when made public, provoked a sharp protest from the Orange County chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, as well as the feisty libertarian publisher-editor of the Santa Ana Register, R. C. Hoiles, who had editorially opposed the 1942 exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans and later, in 1945, had vigorously campaigned for Orange Countians to welcome, in a spirit of democratic humanitarianism, the county’s returning Japanese Americans residents.

As public reaction in the county as a whole became intensely supportive on behalf of the Masudas, the cemetery manager reversed himself and allowed them the plot they desired for the burial of their son. Finally, on December 9, 1948, Kazuo Masuda came home.

Pallbearers with Sgt. Kazuo Masuda’s Coffin (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

On that day, in a funeral service with full military honors, he was buried in a “desirable” section of the Westminster Memorial Park.

In the years following Kazuo Masuda’s re-burial in Orange County, his name and his and his family’s story have become memorialized. November 2, 1957, witnessed the mustering in of the Kazuo Masuda Memorial Post 3670 of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in Huntington Beach.

Members of Kazuo Masuda VFW Memorial Post (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

Then, on December 17, 1975, the Kazuo Masuda School in Fountain Valley was dedicated; it was the first American public school named for a Nisei.

Kazuo Masuda School Dedication Ceremony (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

Later a Japanese garden was developed at the school, which in 1983 was converted from an elementary school into a middle-school.

One additional chapter to the story of the Masuda family and its war hero son, Kazuo, was developed in relation to the culmination of the historic Japanese American redress and reparation movement. That movement began in the 1970s when community activists began to campaign for some kind of “redress” for their wartime incarceration. This campaign led to President Jimmy Carter signing a bill in 1980 creating the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to determine whether any wrongs had been committed in the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

This blue-ribbon committee held hearings across the nation, and it was in these hearings that hundreds of Nikkei survivors of the wartime camps told their stories, often for the very first time. In 1983, following its detailed investigation, the Commission found that a grave injustice had been done to Japanese Americans, and the Commission recommend that the federal government should formally apologize and that each survivor should be granted a tax-free payment of $20,000. Five years later, after the House of Representatives and the Senate had voted to support these recommended redress measures, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 still needed to be signed into law by the then president of the United States, Ronald Reagan. In the years since his 1945 talk at the Santa Ana Bowl Ronald Reagan had moved substantially from the left to the right of the political spectrum.

Thus, there was a widespread fear among the bipartisan Congressional supporters of redress that President Reagan, who, among other things, objected to the $1.3-billion price tag involved, would veto the Civil Rights Act legislation. Press reports indicated that a veto was coming.

On November 19, 1987, June Masuda Goto, Kazuo’s youngest sister, wrote a letter to President Reagan reminding him of his words at the Santa Ana Bowl on December 8, 1945, and urging him to look favorably upon redress legislation should it arrive on his desk. The letter had been drafted by Grant Ujifusa, JACL redress strategy chair, and was delivered to the White House by Governor Thomas Kean of New Jersey via a special line of access used by Republican governors. Ujifusa was Kean’s book editor in New York. After reading the letter, the president called Governor Kean and said that he remembered being at the ceremony for Kaz Masuda, that he had changed his mind, and that he was going to sign the redress bill.

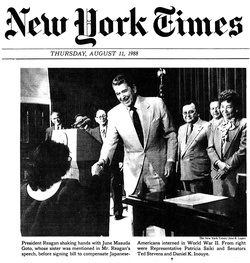

At the August 10, 1988, signing ceremony, in which June Masuda Goto was present, President Reagan recounted the Masuda story, placing special emphasis on the events in Talbert and Santa Ana on December 8, 1945. He then repeated the words that day of someone who he referred to as “a young actor,” after which he said: “The name of that actor, and I hope I pronounce it right, was Ronald Reagan. And yes, the ideal of liberty and justice for all, that is still the American way. Thank you and God bless you. And now, let me sign H.R. 442, the redress bill for Japanese Americans, so fittingly named in honor of the 442nd. Thank you all again, and God bless you all. I think this is a fine day."

The late Clarence Iwao Nishizu, the person most responsible for the construction of the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, was at the signing of the Civil Liberties Act. According to his oral history in the archives of the CSUF Center for Oral and Public History, this is the memory that Clarence Nishizu took away from this event: “The President then signed the bill. I noticed that the first person whose hand the president shook after that was June Masuda Goto’s. He used both of his hands, holding his left hand over her hand to indicate sincerity. It was a very special moment for me.” It was also a very special moment for American democracy and fair play.

(END)

* This was a presentation at a public program in support of New Birth of Freedom: Civil War to Civil Rights in California at the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, Fullerton Arboretum, California State University, Fullerton on October 19, 2011

© 2011 Arthur A. Hansen