Barefoot Journalism. A three-headed Japanese monster. Youth struggling to define themselves in a society still healing itself yet turning its judgmental eyes upon victims. What relationship could these three entities possibly share?

In April 1969 a group of students at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) founded a newspaper dubbed Gidra, a monthly publication that took a radically progressive political position. These five students—Mike Murase, Dinora Gil, Laura Ho, Colin Watanabe, and Tracy Okida—desired a visual media that would bring to light issues not featured in the mainstream media. Dubbed by the authors as the “Voice of the Asian American Movement” Gidra ran from 1969 until its final issue was published in April 1974.

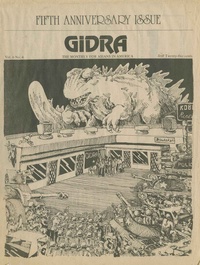

The newspaper took its name from King Ghidora, the villain from the popular film Godzilla. Ghidorah was a three-headed winged monster, an enemy of the public. While portrayed as the antagonist, Ghidorah should not be blindly vilified but recognized as an entity resisting an oppressive system that sought to eradicate his existence. Likewise, these Asian American youth were a growing force opposing a society that oppressed them.

The 1960s is known as the era of the Civil Rights Movement, however the breadth of this movement is little recognized. One such voice rising among the masses was that of Asian Americans. Gidra is a prime example of an exemplary group of Asian American students making their own contributions to what they felt was the Asian American voice.

Robert Nakamura describes Gidra as not being “about art, it wasn’t about self-expression, it wasn’t even about breaking stereotypes to the majority society. We wanted to break stereotypes to ourselves.” The hostility that drove Japanese Americans into concentration camps during World War II did not end with the war nor with the release of these wrongfully incarcerated 120,000 individuals. The war’s end did not mean the negative sentiments towards Japanese Americans also ended. Racism remained deeply ingrained in Los Angeles, and these Nikkei were not only forced to deal with their experiences of incarceration but the stigma that subsequently followed.

Gidra allowed its authors a space to place political and cultural issues in the United States into the context of its imperialist policies abroad and to see the Asian American Movement as a whole. The domestic racial injustices could be correlated with aggressive policies in Asia.

As predominantly Japanese American authors, their main focus was that of the incarceration of Japanese Americans and though each subset of Asian Americans had their own unique experience they dealt with a similar struggle to define their identity and fight against the stigma held towards them. With the WWII incarceration, these authors needed a space in which they could discuss this “buried trauma” and express their hidden emotions. It allowed them to come to terms with what they held repressed within themselves.

The post-concentration camp experience could be said to be more traumatic than incarceration because even with the end of the war they could not come back to the lifestyle they once knew. The hostility and racism caused them to develop a negative self-image of themselves as Japanese Americans. The city they returned to bred self-hate and many became reluctant to associate with other Asian Americans, believing that in doing so they could escape this stigma. The hostility and sense of inferiority even lead some to consider rejecting their Japanese heritage.

Rather than focusing on the negative history that came to be associated with Asian Americans, the Movement brought about a new perspective where the Gidra authors could take pride in their past. Gidra gave them an opportunity to work with and find those who shared the same sentiments, who felt the same way, in order for them to come to terms with their past as well as their future.

The topics that Gidra covered were not only particular to the Japanese American incarceration, but they dealt with the anti-war sentiment during the Vietnam War, the rising skepticism of the effectiveness of demonstrations and rallies, “yellow” prostitution, drug use in the Asian American community, and third world oppression in areas such as Africa, broadening its range onto the global scale. It became not just a story of Japanese Americans, but Asian Americans working towards effective constructive changes in a society that shadowed the struggles of the oppressed.

Given the nature of work compiled in the Gidra publications, the time invested into the newspaper was not about making money or necessarily informing those unfamiliar with the dilemmas of Asian Americans. It was about collaboration, a community service, and self-development that allowed the very individuals who were so deeply entrenched in the issues to gain an awareness within themselves. The power of the visual media lies in its ability to enlighten someone emotionally, even if not intellectually.

The staff of the newspaper had no clearly demarcated hierarchy, as every individual held an equal voice. Although this lack of the traditional executive structure made for long hours and agreements were slow to come, this system offered a sense of humility and equal standing. Here there were no select, privileged few who made the decisions without fully taking into account the voice of all the people, to provide a more wholesome and balanced perspective.

Because the material addressed a wide audience, and was with radical views, Evelyn Yoshimura, an editor of Gidra, states that, “You had to deliver the message in a palatable way—in a way that people could relate to it. I think that was inspiration for using so many graphics and to illustrate things in a way other than text.” The newspaper contains a rich text, but what is eye-catching are the illustrations, photographs, comics, and caricatures that give Gidra character. The visual media aspect of the newspaper allowed these youth to take a radical departure away from mainstream media.

Even today what is necessary is to not be easily swayed by the mainstream media but instead have the courage to be actively engaged in the world around us. Rather than readily accepting the world as it is, we should actively engage in the world around us and take what the media says with a grain of salt.

Those who took part in Gidra provided a new perspective about what we have come to regard as activism. For these young publishers this newspaper provided them with a space to discover their identities, develop a new media to address community issues, and give hope for the future. Without the struggle there would be no change.

The privileges we have today are a result of the hardships and determination of the few who took it upon themselves to vocalize the sentiments shared by many. It may not have been the popular opinion, and it may even have been against the very beliefs by the media and the majority, but I believe it was the right one.

There were times when having such a small staff Gidra nearly failed to meet deadlines, even with the grueling hours they invested. But they persevered, never forgot humility, and collectively shared their strength as individuals who genuinely cared for the cause and struggle. They produced not just a newspaper, but also an experience rich with brotherhood and sisterhood towards a new dynamic to interpret history and the making of culture.

“That’s how you really bond—you struggle…We didn’t burn out, we didn’t get cynical, we’re still hopeful, we’re still trying to do things that fit the conditions of today.” Just as Mike Murase firmly believes, Gidra may have only been published for five years, but the consciousness of these activists continues to live beyond the scope of the newspaper.

If you are interested in Gidra or the artwork of Asian Americans influenced by this newspaper you can view them and more in the exhibition, Drawing the Line: Japanese American Art, Design & Activism in Post-War Los Angeles, on view at the Japanese American National Museum through February 19, 2012. Peruse the artwork and you will gain an enriching insight into how the Asian American voice can be portrayed through an artistic medium, and perhaps you too will be inspired to learn about the drive behind these works and the history intertwined with them.

Click here to read issues of Gidra magazine >>

Watch a clip from "Drawing the Line - Gidra" >>

© 2012 Yoshimi Kawashima