Read Part 2 >>

In all, the documents and letters, even telegrams, showed that there were many pleas for hearings to be held so that he could make a case for his parole and release. All of his and the family’s pleas were turned down. The main reason given was that there was never any new evidence introduced to make them change their original judgment. While the family’s efforts were well-meaning, I also could not see any new reasons for their appeals until the family faced a tragic loss.

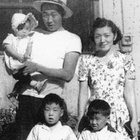

It was when Jichan’s oldest son Hiroshi, while working on an Amache construction project, was fatally injured, that Jichan’s separate imprisonment situation would change. A pile-driver, Hiroshi and his work crew were using on a canal project near Amache jammed. Mechanically adept Hiroshi clambered up to undo the jam and when it suddenly gave, he was struck in the chest impaling his lung. He was rushed back to the Amache hospital where he died the following evening, June 8, 1943, leaving pregnant auntie Dorothy Yoshiko, 28 a widow and cousins Kenneth Hiroichi, 4 and Phyllis Yaeko, 3 without a father (photo-1, above). Baby Carol Hiroko, was born July 5, never to know her daddy.

Jichan was permitted to attend the funeral and was able to spend two-weeks with the reassembled family, by then six family members were out of Amache and hastily returned for a sad reunion. After the funeral, the six family members left to continue their lives outside of the prison camp and Jichan was escorted back to the Santa Fe Detention Camp, re-imprisoned to grieve alone.

Now, the letter writing took on a more urgent and emotional tone. From Hiroshi’s widow, Dorothy Yoshiko, in a hand-written 3-page letter (19430621), she wrote about the increased hardship of raising an infant daughter and two children. Hiroshi’s siblings wrote about the increased pressures on their ill mother who already was caring for grandchildren while her daughter, my mother, was recovering from a surgery. Also, her next oldest son, Saburo, 21 left Amache to attend the US Army MIS language school at Camp Savage, Minnesota and the next oldest, Hirofumi, 19 was in Chicago looking for work to help assist the family financially. Almost 18, Toshihiko was planning to go to work in Chicago as well.

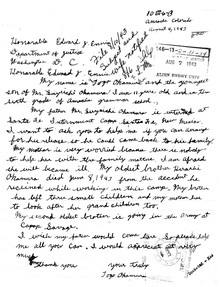

Here is the first of three letters, (19430804, right), written by eleven-year-old Togo at this time of their family’s unsettling situation. This letter dealt with the death of his oldest brother, Hiroshi and that the fact that the next eldest was going into the US Army. While I have read letters in response to the letters written by the adults, I haven’t seen any in response to Togo. Did they not take this young boy seriously or are those response documents missing? Although I’ve received over 190 pages of documents from the National Archives, I do see some evidences of not having received all the documents, so possibly they did respond to this 11-year-old?

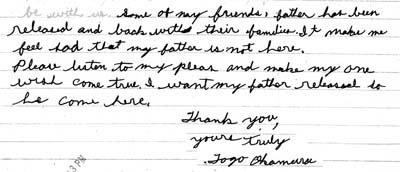

In his second letter (19430909, below) I cropped it to show his plea more clearly. While his friend’s fathers were released, his father was not.

In all of the government’s denials, too much was made of jichan’s and other Isseis’ membership in the various Japanese associations. All ethnic groups that immigrated to the United States of America were by necessity forced to unite in tight-knit communities and associations, because they were not allowed to blend into the American mainstream. They like the Blacks couldn’t use public swimming pools, join and use common community centers, have easy access to medical care, restaurants, etc., etc.

These “dangerous Aliens” were but political pawns to appease the ‘free’ U.S. citizens that their government was doing its job to protect them. In “Judgment Without Trial,” Tetsuden Kashima states regarding the hearing board process, “The committee’s final recommendation reveals the importance of public relations rationale and the government’s interest in assuaging public fears: “In spite of unanimous decision of the judges and the identical nature of the cases, half of them were sent (paroled) to the Japanese relocation centers and half were kept in detention to ‘satisfy public opinion.’” Jiichan was unluckily in the wrong half!

Jichan’s membership in the Togo Kai, an admiration society that revered Admiral Togo Heihachiro, seemed to be the main sticking point and reason for denying his release.

“Admiral Togo Heihachiro, who was born in Kagoshima-ken (the same prefecture my grandfather was), learned his seaman skills in naval colleges in England, from 1871–1878. Aboard HMS Hampshire, the British Navy training ship he circumnavigated the World. Following his graduation and return to Japan, he had a long and highly successful career as a major Japanese Navy leader. On his death in 1934 at the age of 86, he was accorded a state funeral. The navies of Great Britain, United States, Netherlands, France, Italy and China all sent ships to a naval parade in his honor in Tokyo Bay.” (Wikipedia)

I recall after the war that Jichan did have a picture of Admiral Togo on the wall in his home. I suspect that he must have had it stored away during the forced evacuation in the basement of Benkyodo and his home. Jichan was very fortunate to have had his properties under the care of trusted Crocker Anglo Bank personnel.

My Sansei cousin Rick, who co-owns and operates Benkyodo today was born two-months after Uncle Tom Togo, age 20 was killed in action November 23, 1951 in what must have been a scary battle in the Korean War. Rick, born January 27, 1952, told me “that his father (Hirofumi) gave him the middle Japanese name Togo in honor of his kid brother who he was very proud.”

It wasn’t until over a half a year later after Hiroshi’s funeral that Jichan was finally granted parole to join Bachan in Amache. By then, the only immediate family members left to reunite with were Bachan, Auntie Yuki and Uncle Togo.

I wish the letters, that surely must have been ‘flying’ back and forth, directly between Jichan and his family members for over two-years, existed. I’m sure they would have more emotionally reflected an even higher level of drama that was being played-out by their separation and those anxious war years.

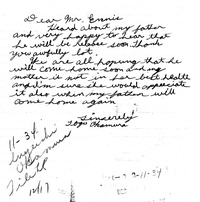

Lastly, I will insert a copy of Uncle Togo’s third and final letter (19431217, right) from Amache, thanking Edward J. Ennis, Director, Alien Enemy Control Unit, Department of Justice for the decision to finally release his father to join him in Amache, which according to an INS memo (19440202), noted that his father was finally back in Amache in February 1944.

Uncle Togo, who would die for his country eight years later fighting against ‘another’ Asian enemy, wrote just three of the many, many “letters from camp” asking for his father’s freedom while imprisoned himself. He wrote this last letter from camp in gratitude.

*All photos are the courtesy of Gary Ono

** To see the documents (referenced by date), go to the Nikkei Album "Letters From Camp". There are documents and individual letters written by each of the Okamura siblings, Amache Camp Director, US Attorney General, etc. Not all 190-pages, but selected key ones to this story.

© 2011 Gary Ono