Read Part 16 >>

Miyatake and Adams

Photography also provided Miyatake an introduction to Adams at Manzanar. Introduced by Merritt in 1943, their shared passion for photography and the discovery that Edward Weston was a mutual friend forged the beginning of a lifelong friendship between Miyatake and Adams. Archie remembered the day when Adams came to their barrack to photograph his family, resulting in a picture that Adams included in Born Free and Equal. In it, Toyo stands, hand on hip, watching his daughter Minnie drawing (by then, two more Miyatake children, Richard and Minnie had been born). Hiroko leans over Minnie with an approving look, while Archie appears in profile on the bed, looking at his sister. Richard looks at the camera. Dolls, a toy train set, childrens’ books and numerous hand-drawn pictures on display could be the accessories of any ordinary child’s room. Among the pictures taped to the wall, an illustration, perhaps from a book or magazine, of a Caucasian girl kneeling at her bedside, hands placed together in prayer reassures the viewer that this is a Christian family.

The Miyatakes in their barrack at Manzanar. Photograph by Ansel Adams (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

“After the picture was taken,” Archie recalled, “Ansel Adams sat down and talked with my father for quite a long time. That’s when they talked about Edward Weston.” Suddenly, Adams spotted Minnie’s toy piano. “He put it on his lap and started playing a classical piece. My father named that tune because he was very interested in classical music,” Archie recalled, and Adams told them that he had intended to become a concert pianist before selecting a career in photography.

Miyatake loaned Adams his darkroom during his three trips to Manzanar, but the visiting photographer used it only to load film since the primitive conditions did not meet his exacting technical standards. By all accounts, Adams was a friendly presence who was admired and respected by prisoners. “I remember him driving that great big Lincoln sedan,” says Archie. “He had a platform on top where he would set up to take pictures from. A lot of the Japanese in camp resented the fact that they were there, and they were not too happy with the U.S. government and the way they were being treated. And yet he came into the camp just to record it. Then, to donate the whole collection to the Library of Congress…” his voice trails off in a vapor of appreciation.

Interpreting Miyatake’s Manzanar Photographs

Those who seek in Miyatake's photographs of Manzanar the outrage of a Lange, or even Adams’s crafting of a wholesome and wholly American image of the prisoners, will be disappointed. Although Miyatake lived in the hothouse environment of simmering anger, fear and suspicion that some Manzanar chroniclers have described, his photographs bear no signs of violence or anger.

Instead, they show Miyatake’s connection to and his membership in the community he was documenting. While Adams and Lange photographed Manzanar to explain to outsiders what was going on inside the prison camp, Miyatake’s audience was his fellow Japanese, those imprisoned with him, and perhaps an imagined, future audience of Japanese Americans who would look to his photographs to understand what it was like to be a prisoner at Manzanar.

Some of Miyatake’s photographs reveal the impoverished, ramshackle quality of the prison camp facilities and the desolation of the landscape, hinting at the difficulty of life in the camp. Yet Miyatake also captured positive images that offered his fellow inmates encouragement in the face of bleak circumstances. In their catalog, the curators of the 1977 exhibit “Two Views of Manzanar” noted the diary-like quality and the absence of scenes of strife in Miyatake’s work, calling him “an almost omniscient observer of life within the camp,” who “sought to affirm the growth and quality of life” in his community rather than “recording the suffering of dislocation.” These life-affirming pictures include scenes of the cherished ritual of mochi (rice cake) making, a smiling family around a new baby, a master gardener tending his chrysanthemums. They exhibit the prosaic quality of family snapshots, a matter-of-fact, “I-was-there-and-this-is-what- happened,” feel. As with Peter K. Simpson’s interpretation of concentration camp photographs, it is the viewer’s knowledge or lack of knowledge of the injustice and humiliation of the experience that make viewing Miyatake’s photographs a powerfully moving experience or a neutral one.

Jasmine Alinder, who provided eloquent analysis of Miyatake in Moving Images, believes “it’s not fair to place representational burden on [Miyatake’s] shoulders” or to demand that he express an overt political point of view. She describes an interview of Miyatake in which the interviewer seemed intent on drawing him out as a crusading visual chronicler of repression, conflict and violence in camp. “The interviewer had a very specific agenda. He wanted to know where Miyatake was during the Manzanar riot. Miyatake was in his barrack. He didn’t run out to take pictures of the riot. Toyo had a lot he wanted to say about photography, but his interviewer couldn’t have cared less.”

Miyatake’s importance, believes Alinder, lies in the fact that he reclaimed control of the camera and the right to photographic representation. He took back the instrument that had been criminalized in the hands of Japanese people, and used as a tool of surveillance and control over them. The very act of photographing, before his secret camera was discovered and before he was made official prison camp photographer, was an act of resistance, an assertion of his right to freedom. The fact that photography was for Miyatake linked to personal survival gives his work an urgency that even the powerful images of Lange and Adams cannot match.

The Post-War Years

Grand opening of the Kinema Theater, Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, August 1955. Photograph by Toyo Miyatake Studio. (Gift of the Alan Miyatake family to the Japanese American National Museum [96.267.289])

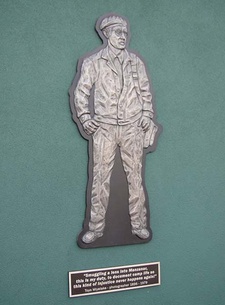

Toyo Miyatake’s accomplishments have not been as widely recognized as those of Ansel Adams and Dorthea Lange, in part because unlike Lange and Adams’s Manzanar photographs, they are not in the public domain. Nearly all the images are owned by the Miyatake family, and subject to copyright protection. Yet in the Japanese-American community, Miyatake is a legendary figure. An enlarged bronze replica of Miyatake’s handmade camera, a symbol of his prominence in that world, testifies to this fact and holds a place of honor on East First Street in Little Tokyo. In February, a bronze replica of the photographer and a street bearing his name were inaugurated on San Pedro Street between East Second and East Third Streets.

In his later years, Miyatake collected awards and tributes from both sides of the Pacific Ocean. The lionized photographer was named grand marshal of the Nisei Week Festival in Los Angeles in August 1978, after which 600 people attended the awards banquet held in his honor. Over 50 years of documenting everything and everyone of note among the Los Angeles Japanese community had made him, as one chronicler called him, “the walking encyclopedia of Little Tokyo.” When he died in February 1979, more than 2,000 friends and admirers flocked to Koyasan Buddhist Temple in Little Tokyo, a line of people stretching half-way around the block as friends and admirers waited to pay their respects.

Artist Nobuho Nagasawa’s enlarged bronze replica of Miyatake’s makeshift Manzanar camera, East First Street, Los Angeles.

Full-scale bronze relief of Toyo Miyatake, San Pedro Street, Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. Photograph by Nancy Matsumoto

The recently renamed Toyo Miyatake Way, off San Pedro Street in Little Tokyo. Photograph by Nancy Matsumoto.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto