Read Part 2 >>

PLANTATION LIFE AND LABOR

As the last ethnic group to be recruited in the nineteenth century, the Japanese entered at the very bottom of the plantation system. In 1892, they constituted more than 65 percent of the workforce but received the lowest wages and were given the poorest housing. Skilled and supervisory positions were almost exclusively reserved for whites.1

“The gap between plantation managers and immigrant workers was wider than that existed between the lord and peasant during the feudal days in Japan,” reported Issei newspaper publisher Yasutaro Soga. “It was comparable to the relations between the negro slaves and their masters in the southern part of the United States.”2

Living conditions reflected the plantation hierarchy. At the top lived the white American, German, and British managers in spacious mansions. Next came the well-kept cottages of the Portuguese and Spanish who were the field overseers (lunas). At the bottom were the wooden-framed barracks of the Japanese camps.3

Miki Sato, the Japanese Consul General, reported after an inspection of Maui and Hawaii in 1899:

At one camp six families are forces to stay in a single house of 12x30 feel without any partitions. At other plantations several hundred persons of both sexes are also mixed up and kept in one large square house without any partition in it. Their sleeping bunks are long shelves of rough wooden boards, consisting of four stories…Each bottom shelf in every row is given to one married couple, the other three upper shelves being given to single men.4

All plantation workers were issued a bango (employee identification number). The metal tags had a different shape for each ethnic group. Workers had to present their tags to collect their monthly wage. Chosoku Kochi had no problem remembering his number “3939” or sankyu sankyu in Japanese. “I remembered my number as ‘sank you, sank you’” the way a Japanese would say “thank you” in English.5

When the whistle shrieked at 4:15 A.M. to rouse the workers, Haruno Tazawa, who came to Hawaii as a picture bride in 1917, was already awake. She was cooking the rice on an open fire and preparing lunch for herself and her husband Chozo. Pickled vegetables (tsukemono), pickled plums (ume), boiled vegetables (okazu), and rice was the usual meal. She hurridly packed the food in a doubled-tiered lunch tin along with a gallon of water in a denim bag. She knew that by 4:30 A.M. she had to be out the door to catch the train for the hour-and-fifteen minute ride to the cane fields.

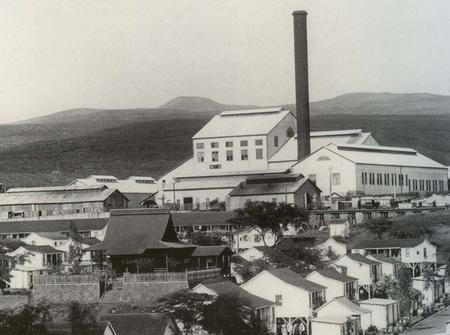

C. Brewer's Honolulu plantation mill (1898-1946) Aiea, Oahu, ca. 1910. Gift in Memory of Mrs. Tome Yoshida, Japanese American National Museum (91.90.154)

Mindful of the searing Hawaii sun and the razor-sharp leaves of the sugar cane, Haruno readied herself for work. “The first thing I put on was the long underpants (momohiki),” she explained. Next came the denim leggings (kyahan), a tie-dye (kasuri) jacket, dirndl skirt, and a rectangular cotton towel (tenugui) tied securely around her head to protect her face and hair from the sun and dust. She wrapped a black sash (obi) twice around her waist before she slipped handcoverings (tesashi) over her rough hands. Finally, she put on a straw hat (mugiwara bo) which she secured with a hat pin and a bleached rice bag folded diagonally and placed over her hat and tied at the chin.6

Plantation workers were divided into work gangs of 20 to 30 laborers and each gang was assigned to various tasks of cutting, planting, irrigating, weeding, fertilizing, and loading the cane onto tram cars, wagons or flumes to transport to the mills. In the fields the women were generally assigned to hoeing, stripping cane leaves, harvesting or fertilizing the sugar cane. Haruno carried buckets of fertilizer to spread evenly over the fields. Like the other women, she was on the bottom of the pay scale. In 1915, a Japanese female field hand was paid an average of fifty-five cents per day compared to seventy-eight cents for her male counterpart.

In the fields the women sang the hole hole bushi7, songs they composed based on traditional Japanese folk songs, while watering the plants and stripping away the dead leaves from the sugar cane stalks.

Wonderful Hawaii, or so I heard

One look and it seems like Hell.

The Manager’s the Devil and

His lunas are demons.8

Few escaped the watchful eye of the lunas (foremen), who sometimes used their whips to extract the greatest amount of work. “If we thought the lunas were coming, we were afraid,” remembered Tsuru Yamauchi. “Both men and women worked very hard, because we were scared.”9

After five hours of work, a whistle blew and someone called “kau kau time!” The workers had half and hour to eat their lunch before they heard, “Shigoto time!” (“Back to work!”) When the last whistle blew at 4:30 p.m., everyone knew it was pau hana (end of work time). That’s when Kakusuke Oshiro would tear through the fields to beat the others back home. “We all took a bath together,” he recalled. “If, however, you got in last, it would be very dirty.…For that reason I’d come running.…By the time everyone got back I’d already taken a bath.”10

During the early days of plantation life, women were scarce and gambling was rampant. Most of the men had “no families to return to after a day’s hard work,” reported Taro Ando, the Japanese Consul General from 1886 to 1888, “and out of sheer loneliness seek solace in gambling, drinking and the companionship of women with questionable morals,”11 The arrival of “picture brides” from 1908 to 1924 improved the sex ratio, but until the turn of the century, there was a constant ratio of four men to each women.

To supplement the family income, many women also sewed, cooked, and did laundry for the large number of single men living in the plantation camps. Haruno Tazawa was no exception. “I worked in the fields for ten hours a day….I also did laundry for the Filipino bachelors. I worked without hardly any sleep….trying to make ends meet. It was frustrating. No matter how hard I worked, there never seemed to be enough”

My husband cuts the cane,

I do the hole hole

By sweat and tears

We get by.12

“Mill, mill,” the Issei used to say, preferring to work there then in the fields. Though the hours were longer, the wages were higher and the work less strenuous. “Anyplace (sic) you go in the mill, the work is easier,” remarked Kosuke Teruya, “our clothes didn’t get dirty either.”13

At the mills the cane stalks were washed and crushed to extract the juice. The juice was boiled, condensed, crystallized into sugar, then bagged and shipped to refineries in California. The workers in the mills were supervised by engineers and other technicians operating engines, boilers, furnaces, presses, and other machines. Carpenters, electricians, ironworkers, and mechanics rounded out the supporting services required to keep the plantation in operation.

The Masters and Servants Act of 1850 laid the legal foundation for the enforcement of the contract-labor system in the courts. Workers were bound by law to their three-to-five year contracts and imprisoned, fined, or forced to serve additional years if they failed to fulfill their contracts.

However, the fear of being caught didn’t stop the Issei from defying the system. Torahichi Tsukahara remembered, “There were lots of them who ran away from the plantations, breaking their contracts” and making their way to Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii. Some changed their last names to escape detection of plantation managers, sheriffs, and hired bounty hunters.14 Before the end of contract labor in 1900, losses by desertion had become quite a problem for the planters.

Notes:

1. A 1904 resolution restricted skilled positions to “American citizens or those eligible for citizenship” which automatically eliminated Asians who, by federal law, were ineligible to become naturalized.

2. Keiko Soga, Gojunen No Kaiko (1953), p. 11, in James H. Okahata, A History of Japanese in Hawaii, p. 123.

3. Before 1900, Hawaii’s housing law required plantations to provide only 300 cubic feet per laborer.

4. In Roland Kotani, The Japanese in Hawaii: A Century of Struggle, p. 16.

5. Chosoku Kochi oral history, Uchinanchu, p. 431.

6. Haruno Tazawa, January 15, 1984, oral history conducted by Barbara Kawakami.

7. Hole hole is the Hawaiian term for dried sugarcane leaves and bushi is the Japanese word for melody.

8. In Roland Kotani, The Japanese in Hawaii: A Century of Struggle, p.14.

9. Tsuru Yamauchi oral history, Uchinanchu, p. 495.

10. Kakusuke Oshiro oral history, Uchinanchu, p. 382.

11. Franklin Odo and Kazuko Sinoto, A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawaii 1885-1924, p. 76.

12. In Roland Kotani, The Japanese in Hawaii, p. 13.

13. Kosuke Teruya oral history, Uchinanchu, p. 524.

14. Torahichi Tsukahara oral history, Uchinanchu, p. 1270.

* Issei Pioneers: Hawai‘i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 is the catalogue accompanying the National Museum’s inaugural exhibition. Using artifacts from the National Museum’s collection to tell the story of the courageous “Issei Pioneers,” the catalogue focuses on the early immigration and settlement years. To order the catalogue >>

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum