One of the most famous Canadian Nisei names is that of Raymond Moriyama, the internationally renowned architect of the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, the new Canadian War Museum in Ottawa and the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto.

Moriyama, 80, was imprisoned along with 21,000 Canadian Nikkei during World War Two. His family was held at the Bayfarm, British Columbia internment camp. It was during this tumultuous period of his life that he built his famous ‘treehouse’ which has since been the inspiration of many of his award-winning designs.

Founded in 1958 by Raymond Moriyama in Toronto, Canada, Moriyama & Teshima has built its reputation on distinctive landmark. Founder Raymond Moriyama started the firm as a sole practitioner in 1958. Ted Teshima, who joined the firm full-time in 1966, became a partner in Moriyama & Teshima Architects and Planners in 1970. Under their direction Moriyama & Teshima prospered and grew building a world-renowned reputation for work in architecture, interior architecture, planning and landscape architecture. Raymond and Ted are now consultants to the firm.

On May 1, 1958, with $392.00 in the bank, Raymond Moriyama set up practice as a sole practitioner on the second floor of a semi-detached house at 71 Yorkville Avenue. Three rooms were shared with Klein and Sears Architects who started business on the very same day. Doors on saw horses became drafting boards.

The firm’s very first project was a cottage in Algonquin Park, designed for Mrs. Lazir. The project came in on budget: $8,000, including fees. Ray, his wife Sachi, and their three children stayed at the cottage for a week to make sure every detail was perfected.

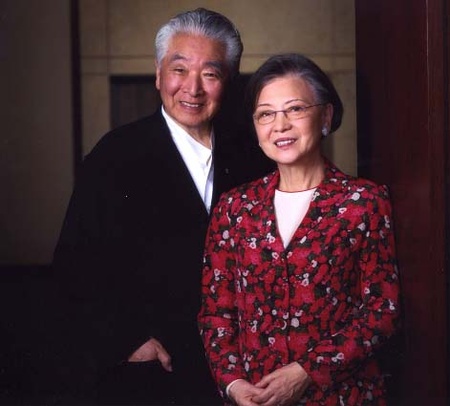

Ray and Sachi Moriyama had worked together for over 10 years to determine the best location for the JCCC, mapping out the addresses of all the Japanese Canadians in Toronto and forecasting patterns of future movement. The Cultural Centre was so carefully designed that only eleven concrete blocks required cutting to size.

The following are excerpts from a speech that Mr. Moriyama made at the Sakura Ball at the Toronto Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre on April 10, 2010.

***

Last December 28th, 2009, Sachi and I celebrated 78 years of ‘knowing each other.’ When we first met she was 2.5 months old and I was 2. Our parents were great friends. They were meeting for a pre-New Year get-together, a quiet two family get-together which included the two of us.

We were both born in Vancouver and grew up together on the same block, on the same north side of 100 Cordova Street East. She used to call me “Bozo” and “Yancha”, but I knew she liked me.

She played the koto and tap-danced. When I saw her perform a tap when she was 6, she was not only my best friend, but she became my Shirley Temple. That night I told my father that I was going to marry her after I become an architect. My father chuckled and with a twinkle said, “You’re 8, Junichi (father and mother always used my Japanese name when they were very serious or pulling my leg).

“You may change your mind. If you persist, you’re going to be either very consistent or very boring.”

I was determined to be consistent, even boring. Fortunately, Sachi decided to marry me. In her gentle way she created a sanctuary for a home, a playground for the children, and provided that consistency that allowed us to raise five children quietly, to meet life’s unexpectedness including a roller coaster life of an architect.

I was asked to give a speech on what I learned in 80 years. However, the The Good news: I didn’t learn much of importance after I was 13. I, therefore asked myself, what should I have learned a lot more in 80 years? There were so many things I should have learned more. I may be foolish, but I decided that I will try to do this in 5 chapters.

CHAPTER 1—AS A CHILD UNDER THE AGE OF 6

Like most of you, I learned the most important things in life in those early years. I learned not to pee in bed. I learned to use the WC, to use toilet paper, to flush the toilet and wash my hands. I learned to wash my hands 12 times a day (you could figure out that one!), to love my friends, neighbours and to protect my sister…and I learned to hold the chopstick high so I would not marry a short person.

BUT…What should I have learned more!?

Mother’s words were: “Work hard! To be average in Canada you must be 2 to 3 times better than average; to be special, 3 to 5 times better.”

Mother, again: “You were conceived on the first night at sea during a stormy Pacific crossing from Japan in January…I was sick the rest of the crossing to Vancouver so you will never suffer motion sickness.” I never did.

She continued, “So develop your mental gyroscope of balanced judgment and balance the mind and the heart.” I’m still trying.

Father—kind, talented and gentle, a young teacher in Japan: “There are contradictions that need to be left alone, and there are other contradictions to fight and overcome.” He believed also that parents’ primary duty to their children was to be not only kind, but “to prepare for their future freedom as adults.”

At age one, Sachi had a scalding from a kettle full of hot water for tea. At age four, according to my parents, I nearly died, from a bath of boiling stew and was confined to a bed for eight month. To keep me in touch with the outside world, father provided a secret corner at the front of store for me to look outside from my bed.

That’s when God opened a door for me. I watched a construction across the street. I thought it was a beautiful castle. Once in a while a handsome young man with a pipe came to the site with a roll of drawings under his arm. Workers gathered. “Who is that man? Everyone likes him. Who is he? Everyone listens (not today). What does he do?” I asked father.

To find the answer, father went across the street and I saw him talking to the man. He came back and told me, “he calls himself an architect.” An architect!!!! WOW!!! On the spot I decided my life career—an architect. Out of near death and pain came a life-long love affair. God had a strange way of looking after this child.

I did not respond well to the treatments by Vancouver doctors…I was stiff like a wooden puppet. My parents worried and finally sacrificed everything in 1935—in the midst of the Great Depression—to send mother, my sister and myself to Japan to be looked after by my grandfather Sejima’s doctor friend in Tokyo.

My grandfather was a mining executive, but, mostly, I remember him as a handsome samurai poet who wrote spellbinding haiku on his wooden haiku writing platform in his backyard. What did I learn, yet not enough?

One evening, he called out, “Junichi, Junichi, come out and see what I’m watching!” When I ran out, he said, “Look up, in the sky, at the moon, what do you see?”

Hmmmmm…“I see a big rabbit and…more animals doing this and that!” He listened patiently, then asked, “What about the moon? Is it nearly round or fully round, Junichi?”

“It looks round.”

“That’s right, it’s full moon tonight. Isn’t it beautiful!”

“Yes, it’s beautiful.”

Two nights later, grandfather called out again, “Junichi, come out and see this moon.”

“Wow, it’s not the same!”

“Now, Junichi, which is more beautiful—the full moon you saw two nights ago or this one that is waning and not perfect?”

Hmmmm…Before I could answer he said, “Don’t you think it’s this one. In every endeavour you must try for perfection like the full moon yet to a mortal being, magical imperfection is more meaningful, more humane, thus more beautiful”.

MAGICAL IMPERFECTION!

MAGICAL IMPERFECTION!

Must learn more!

He taught me the story of CHUSINGURA, the story of the 47 loyal ronins, samurais without a lord, who lost their master to treachery and after many years gathered and avenged the master’s death, then all of them committed SEPPUKU.

He took me to their shrine, to plays and movies to think about loyalty, dedication, passion, devotion, commitment, and courage—the ways of the samurai. He and I communicated with each other until WWII when all that was abruptly stopped. He wrote to me in English and I in Japanese to him.

© 2010 Norm Ibuki