>> Read part 1

As if the study of Yanagi’s life and theories hadn’t been sufficient, Tatsuo found a formidable mentor within his own family. His uncle Yoshio Sato—his mother’s brother in Sendai—led him intellectually to appreciate Japanese folk crafts and lore. Uncle Yoshio had done a number of guide shows for NHK, and kept extensive journals on local plants, customs, Tohoku linguistics and other anthropological data. “He was a true amateur anthropologist,” Tats said, totally ignoring that many professional anthropologists often excel in amateurishness.

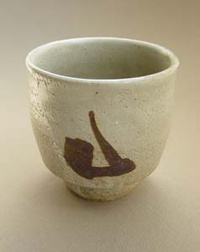

Sansui (landsacpe) Dobin (teapot;) Mashiko, ca. 1900. (this was the type of pot that lured Hamada to Mashiko) (Photo courtesy of Tatsuo Tomeoka)

After school graduation, Tatsuo and his wife moved to Mashiko in Tochigi. Mashiko, only sixty miles north of Tokyo, and very close to Nikko, is a little town of only 25,000 people, but enriched with over FOUR HUNDRED pottery kilns, mind you. It is Japan’s Potters’ Paradise, where anyone, not just traditional artisans, can try a hand at pot making. Mashiko ware, known as mashikoyaki, is a late entrant to the Japanese pottery world; Mashiko established its first kiln in 1858.1 Traditional Mashiko wares were exclusively functional: teapots, water jars, suribachi (grounding bowls) and the like. However due to the influence of Shoji Hamada2 and his famous pupil Tatsuzo Shimaoka, (both designated National Living Treasures), Mashiko is now a home to a legion of both modern and traditional artisans, who produce a delightful variety of styles.

Tats spent a year living at a pottery in Mashiko, and then two-and-a-half years in Yokohama. While teaching English around the Greater Kanto area, he continued his research on Mingei, especially on traditional Mashiko pottery and rural Japanese folk toys.

Our stay in Japan from 1999 to 2002 was a collecting mission that resulted in shipping home a container load of items. It was during this time I had my “aha” moment in terms of collecting Mingei. Even when searching for beauty from ‘anonymous craftsmen’ we all want to find (the) unknown Picasso at a garage sale or thrift store, right? And I was always on the lookout for a good sansui dobin—landscape teapot—from Mashiko. They are not uncommon, but hard to find in good condition. The other part is that they are usually labeled as painted by Minagawa Masu, a woman made famous by Yanagi, Hamada and Leach.3 She was one of the last painters of this style of pot that lured Hamada to Mashiko in 1923.4

After a few years searching, I found a beautiful sansui dobin in good condition, and drove a hard bargain with a dealer in Chiba. Of course it was labeled ‘Mashiko Sansui Dobin, Minagawa Masu.’ I took it back to Mashiko and showed it to Mashiko’s granddaughter Hiro, who had befriended us when we lived there, and who carried the tradition of landscape pottery painting taught to her by Masu. She exclaimed that it was a ‘lovely piece, very early 1900’s’ and then quickly added that it was not painted by grandma Masu. My heart sank a bit, but it was then that I realized that the beauty of Mingei is beyond the name or ego of the craftsman or artist, and well afar from the additional dollar value that pieces of known provenance may attain. The experience helped me reflect on the difference between using the ‘Seeing Eye’ that Yanagi describes in his approach to beauty, and the mere ‘business of collecting.’

Tatsuo is also passionate about tea and the relationship between Mingei and the role of tea in everyday life. After all, Yanagi’s awareness was triggered by a tea cup.5 There was always very good tea at his home, particularly chiran-cha, from Chiran, Kagoshima. Every morning, before leaving for work, his father, a heavy tea drinker, would meditate at his desk, and then prepare his own cup of matcha—powdered tea.

“Having practiced martial arts since my youth, I understood the meditation part…but what was Dad doing mixing up that tea? Didn’t he know how convenient are tea bags to brew your own cup?”

Years later, at the University of Washington, Tatsuo took a class, Introduction to Cha-do—the way of tea. Although he was already familiar with the tea ceremony and its intimacy with the world of Japanese ceramics; it was, as he says, “My first foray into learning tea.”6

“After that, I had the good fortune to be part of many tea gatherings, here in America and in Japan, although I am not a regular practitioner of chano-yu—the formal tea ceremony.”

In 2006, Tatsu did some work for a tea company hoping to build a ‘tea presence’ in North America. After completing that project he was contacted by other Japanese tea companies interested in similar ventures.

Suddenly, without ever trying, I became the tea-guy in America. After numerous discussions, value explorations, and examinations of business models, I decided to launch my own venture: Charaku Fine Japanese Tea, to provide fine tea from a variety of Japanese sources; to help Westerners learn (Japanese) tea, and share the pleasures of its subtleties; and to show the exciting, but very little-known variety of the world of cha. That allows me also an exacting control of the product’s quality. So far, feedback from North American and European customers has been very good.

Tats has always considered his life’s work to be a bridge between Japanese and American cultures; and he pursues this passion by sharing nihon-cha in a Mashiko yunomi tea cup, one sip at a time. He offers an extensive selection of fine teas from various appellations around Japan, through his online site, Charaku Fine Japanese Tea www.charaku-tea.com.

There is also much to enjoy in Tats’ other online site: wasabidou.blogspot.com; bits of history and lore; short, intelligent and understandable gems of history, anthropology and ethnology; tons of graphic materials; an extensive list of local and overseas activities, and quite a few Mingei pieces to tempt collectors.

You’ll love the charming names of his family: wife’s is Apple; daughter’s is Shino Claire; and son’s Yumeji Clay. They live in the beautiful agricultural region of the Skagit Valley—about an hour’s ride north of Seattle.

I sat down to count the tines of the ancient chasen, bamboo whisk, in our kitchen: fifty for the outer skirt, each about a millimeter wide, and fifty more for the body. I wondered who had created from such a small bit of bamboo so much beauty and utility; and whether or not the artisan had intended to have the object used exclusively for chanoyu, the tea ceremony. (I had been using one to stir my cup of cocoa.)

If interested in learning more about the charm of Mingei, try Bernard Leach’s book The Unknown Craftsman, cited in the first part of this piece. Consult JAPAN—An Illustrated Encyclopedia.7 Visit the Internet, particularly the delightful articles by Robert Yellin for The Japan Times—www.e-yakimono.net and Japan’s Mingei Museum page: www.mingeikan.or.jp/english/html/2006-archives.html.

Soba Chokko (soba noodle sauce cups;) Imari porcelain, pattern of dandelions & butterflies, mid-Edo Period (1600-1868.) (Photo courtesy of Tatsuo Tomeoka)

Get the inexpensive and richly illustrated little tome MINGEI—Japan’s Enduring Folk Arts,8 which Amaury Saint-Gilles wrote for the Mingei International Museum of Folk Art.9 Of course, visit our Mingei Museum at its elegant headquarters at Balboa Park, San Diego, or at 155 West Grand Avenue, Escondido; www.mingei.org. Both sites display Mingei and folk art from Asia and other worlds.

Naturally, you could also travel to Japan and visit the Nihon Mingeikan, the Mecca of Mingei. Meanwhile, snoop often at Tats’ sites, identified above, for more learning about Living Mingei.

If tea is your cup of cha, besides Tat’s charaku online site and Okakura’s book, you can have additional fun with Paul Varley and Isao Kumakura’s book: Tea in Japan, U. Hawaii, 1989; and with the excellently illustrated: The Art of Sencha, by Patricia J. Graham. U. Hawaii, 1998.

The images of old and new Mingei items from Mashiko and other areas are from Tatsuo’s business and personal collections, acquired during his many trips to the Japanese countryside. My deep gratitude goes to him, and to Professors Yong-ho Choe (U. Hawaii,) and Burglind Jungmann (UCLA,) and our project coordinator Yoko Nishimura for their enormous help for this piece.

Notes:

1. For a long-distance look at Mashiko, see: wikitravel.org/en/Mashiko. Mashiko claims that its pottery styles are direct descendants from the Jomon (13,000 BC) and Yayoi (500 BC) cultures. See also: gojapan.about.com/od/attractioninkantoregion/a/mashikoyaki.htm

2. Hamada, set up a kiln there, in the 1930’s, aware that Mashiko’s clay is the ideal medium for ceramics.

3. Founders of the original Mingei group in Japan.

4. She was honored by the Emperor for her work of continuing the folkcraft traditions in pottery.

5. Yanagi wrote: “Tea taught people to look at and handle utilitarian objects more carefully than they had before and it inspired in them a deeper interest and greater respect for those objects.” The Unknown Craftsman. Tokyo: Kodansha. 1989. p 148.

6. In cha-do, the way of tea, one ‘learns tea;’ rather than ‘about tea.’ Kakuzo Okakura, the most respected author on “Teaism” says of tea: It is hygiene, for it enforces cleanliness; it is economies, for it shows comfort in simplicity rather than in the complex and costly; it is moral geometry as it defines our sense of proportion to the universe.”-Tokyo: Kenkyusha.1906

7. Tokyo: Kodansha. 1993

8. St. Gilles, Amaury. Mingei: Japan’s Enduring Arts. Tokyo: Tuttle. 1989

9. Art Critic for the Honolulu Star Bulletin.

© 2010 Edward Moreno