Early Japanese Settlers in Oregon

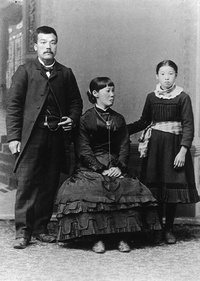

In 1880 27-year-old Miyo Iwakoshi emigrated from Japan to Oregon with her Scottish husband, Andrew McKinnon, and their adopted daughter, Tama. Although there are records of other Japanese visitors earlier, she was the first to settle in the state. She would be one of few Japanese women in Oregon for many years. She and McKinnon built a steam sawmill near Gresham, and named the new settlement Orient in honor of Miyo. The small town of Orient exists to this day. In 1891, Tama married Shintaro Takaki. Theirs was the first Japanese wedding to take place in Oregon.

First settler in Oregon from Japan. Miyo Iwakoshi (seated center) with brother, Riki, and adopted dauther, Tama Jewel Nitobe, Portland, OR, ca. 1886. Courtesy of G. Nomura, Oregon Nikkei Endowment.

By the turn of the century, over 2,500 Japanese were making lives for themselves in Oregon, nearly half in Portland. The majority had come originally as contract laborers for the railroads, logging camps and fish canneries. By 1909, over 30% of Japanese immigrants were working in agriculture. Many managed to become tenant farmers and eventually landowners. Significant Japanese farming communities emerged in Gresham, Hood River, and Salem.

By 1930, more than half of the first-generation Japanese living in Oregon were involved in agriculture, marketing crops worth 3.5 million dollars. They achieved economic success by focusing on crops ignored by white farmers. By 1941, Japanese farmers were producing 45 percent of the asparagus, 60 percent of the green peas, 75 percent of the celery, and 90 percent of the state’s cauliflower and broccoli.

Nihonmachi in Portland

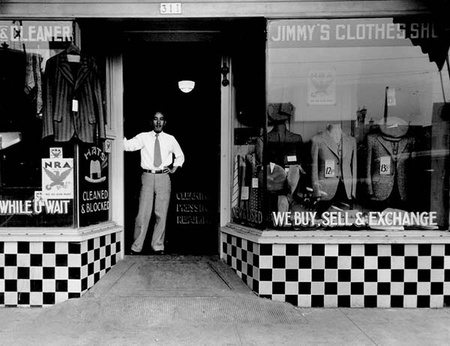

For half a century, Nihonmachi, or Japantown, thrived in Northwest Portland. Japantown served as a staging area for Japanese laborers preparing to take up work on the railroads, in the salmon canneries, and in the sawmills of Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. As Japanese families began to form and settle down, they opened laundries, hotels, groceries, barbershops, and fruit stands throughout the Portland area. Still, Japantown remained a community hub, offering Japanese goods as well as legal, financial, medical and social services for immigrants struggling with English. The Oshu Nippo, Oregon News, the first Japanese language newspaper in Oregon, was published five days a week out of Japantown and distributed throughout the Northwest. By 1940, there were over 100 Japanese businesses operating within this unique community.

Japanese merchants in Portland formed groups like the Hotel Owners’ Union, the Grocery Association, and the Laundry Union. Growers’ guilds were established in the farming communities. A majority of Japanese businesses in Oregon survived the Great Depression of the 1930s. Although times were hard, the ‘30s were remembered as the “good old days” for many Japanese Americans.

Dr. Kei Koyama in his dental office at NW 3rd and Couch St, ca.1941. Courtesy of Miriam Kiso, Oregon Nikkei Endowment.

Racism and Discrimination

The successes of the Japanese immigrants did not go unnoticed in Oregon. As Japanese tenant farmers began to buy land, influential white citizens began lobbying to restrict land ownership. Anti-Asian sentiments among the majority population were not new. Japanese immigrants, along with other Asian groups, were barred from becoming U.S. citizens—even as European immigrants were encouraged to take the pledge of citizenship. The first Alien Land Bill was introduced in the Oregon State Legislature in 1917. In 1923, the bill passed the Senate unanimously and the House with only one dissenting vote. The law prohibited “aliens ineligible to citizenship” from owning, or even leasing, land in Oregon. In Portland, these “aliens” were also barred from operating pool halls, dance halls, pawnshops or soft drink establishments.

Within the year, the United States Congress passed the Exclusion Act, halting immigration from Japan. Faced with this unrelenting discrimination, many first-generation immigrants left. Even as the number of Japanese women increased between 1910 and 1920, overall Japanese population in Oregon dropped by more than 30 percent by the late 1920s.

Oregon in the early decades of the 20th century reflected the attitudes and political biases of the rest of the country. Ku Klux Klan and organizations with similar philosophies were well established and exerted influence on all levels of Oregon’s community life and political leadership.

In 1925, a predominantly Caucasian mob of about fifty men forced a group of Japanese saw mill workers out of their homes and jobs in Toledo, Oregon. Gunfire and fistfights were involved, and Japanese workers and their families fled in fear for their lives. English and Japanese language newspapers in the West Coast actively covered the incident. The grand jury did not find sufficient grounds for indictments. However, the 1926 civil suit filed by the Japanese workers resulted in a judgment in their favor, creating one of the earliest instances of a civil rights case in the United Sates.

Jimmy’s Clothes located at 311 W Burnside Street with owner Masaki Usuda, Portland, OR, ca. 1940. Courtesy of May Hada, Oregon Nikkei Endowment.

© 2006 Oregon Nikkei Endowment