Illinois Japanese Unknown Heroes

Before World War II, there were far fewer Japanese in Chicago than after the war. As a result, more attention has been paid to postwar Chicago Japanese, many of whom chose Chicago as a place to resettle after enduring the humiliation of incarceration camps in the western US. But although they were a small minority in the bustling metropolis of Chicago, the prewar Japanese were in fact unique, colorful, and independent people, perfectly matched to the cosmopolitanism of Chicago, and enjoyed their lives in Chicago. This series would focus on lives of regular Japanese in pre-war Chicago.

Stories from this series

Chapter 2 (Part 6): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—After World War I

Oct. 30, 2022 • Takako Day

Read Chapter 2 (Part 5) >> Unfortunately, after World War I, the tide began to turn for Japanese performers. In February 1922, just before the Immigration Act of 1924 completely barred further immigration from Japan, Consul Kuwashima in Chicago reported to Foreign Minister Uchida as follows: “Peculiar and specialized Japanese entertainers such as singers of Naniwa bushi and biwa players, Rakugo performers, and others cannot earn any profit for performing. Nevertheless, Japanese acrobats still can be seen sometimes performing in …

Chapter 2 (Part 5): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—Kumataro Namba and His Troup

Oct. 23, 2022 • Takako Day

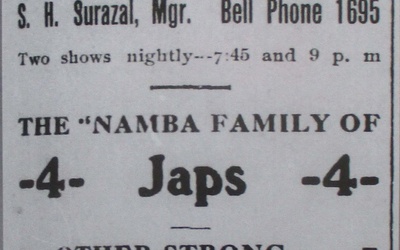

Read Chapter 2 (Part 4) >> By the time the U.S. entered World War I, Namba had moved from 1227 E. 71st to 6348 Dante Avenue in Chicago. Known as the “Namba House,” this address was the haunting of many Japanese performers.1 The other residents were performers such as actor Toyokichi Totsuka, age twenty-four; Katsumi Sato, age twenty-three; Daigoro Fujisawa, age twenty-three; and Asashige Takagi, age twenty-three, who was a jiu-jitsu performer for the Ringling Bros Circus.2 A few years …

Chapter 2 (Part 4): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—Kumataro Namba and Children Acrobats

Oct. 16, 2022 • Takako Day

Read Chapter 2 (Part 3) >> The surname “Namba” appears in the 1910 Chicago census, documenting thirty five-year-old Otra Namba, troupe manager, and Toki Murata, a twenty six-year-old contortionist, as residing at 1227 E. 71st Street in Chicago. Otra had come to the U.S. in 1890 at the age of fifteen, and Murata in 1900.1 While it is not known when Otora Namba came to Chicago, Otora, a vaudeville actress, had married a Japanese animal trainer, Yosaka Kudara, in Mexico …

Chapter 2 (Part 3): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—Growing Up as Acrobats to Be An American

Oct. 9, 2022 • Takako Day

Japanese Acrobats in 1904. (Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division) Read Chapter 2 (Part 3) >> One of the main reasons for the popularity and attraction of Japanese troupes in the U.S. was the inclusion of small children in their performances. For example, Kitamura’s young daughter was named Peach Blossom and her smile was very attractive to the American audience.1 The Tetsuwari troupe “members received their training from the time they were youngsters. They were taught how …

Chapter 2 (Part 2): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—As Residents of Chicago

Oct. 2, 2022 • Takako Day

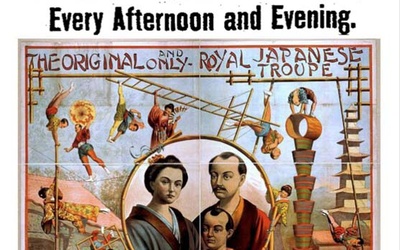

Read Chapter 2 (Part 1) >> One of the new breed of Japanese entertainers who came to stay was Fukumatsu Kitamura, a juggler from Fukui. The Kitamura Troupe was founded exclusively for overseas tours and their first U.S. tour, which included a stop in Chicago, was in 1890.1 They returned to Chicago in 1901 as the Kitamura Imperial Japanese Troupe of acrobats, with seventeen members,2 including Kitamura’s wife, Hisa, age thirty-seven, and his daughter, Kane, age eighteen, who were both jugglers.3 Kitamura …

Chapter 2 (Part 1): Japanese Acrobats and Entertainers in Chicago—Introduction

Sept. 25, 2022 • Takako Day

According to The Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Chicago’s position as the prime city of the Midwest has made it both a necessary stopover on the itinerary of any touring production and a home for a thriving resident theater community.”1 This explains exactly what Chicago represented for Japanese entertainers and why they lived there. In fact, the first Japanese who set foot in Chicago were members of acrobatic troupes who came here even before the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. In …