My mother’s memories of Poston are thick with dust.

When I ask my 93-year-old mother about Poston, she starts with the dust storms. She tells me that when a big storm would sweep in, they would run inside their barrack and huddle there, with towels over their heads to keep the dust out of their eyes and mouths even though they were indoors. Afterwards, “we had to take everything outside – blankets, mattresses, clothes – and shake out all the dust.”

Even when there wasn’t a storm, dust would seep into her family’s single-room barrack apartment through the many cracks and knotholes in the walls and floorboards. “It would collect on the window sills and on the floor, this thick.” She holds her fingers an inch apart.

The dust. The dust. The dust.

When my husband and I attended the 2022 Poston Pilgrimage this October, we walked around the ruins of the Poston I Elementary School – among the few remaining traces of this concentration camp where almost 18,000 Japanese Americans, including my mother and her family, were incarcerated during World War II. We could not stay for the site tour on the second day of the pilgrimage, so we went there a day early, and explored in solitude.

Walking around the ruins is an eerie experience. The classroom buildings are in varying states of decay, victims of vandalism and the elements. All that remains of the auditorium after a 2001 arson fire are the adobe walls and the cornerstone inscribed with the words: “Poston Elementary School Unit I. June 1943. Built by the Japanese Residents of Poston.”

Poston sits in the Arizona desert, but its soil is unlike the beach sand I know from Southern California. It is finer and siltier; it clings. Mom says that when it rained, the dust turned into clay. “When you walked on it, it would come up with your shoes.” She gestures with her hands, miming the gluey hold of the clay on her feet.

As I wandered around the site, I was mindful of the dust. I lifted my feet and stepped gingerly, trying to disturb it as little as possible. But it was futile – my shoes slid on the loose and sandy soil, kicking up puffs of dust with each step. Back at our hotel after just 30 minutes walking among the school ruins, I found dust on my clothes, and in my hair, and a fine film of it on my face. My shoes were coated in dust, and when I took them off, I saw it had penetrated through my socks and collected between my toes.

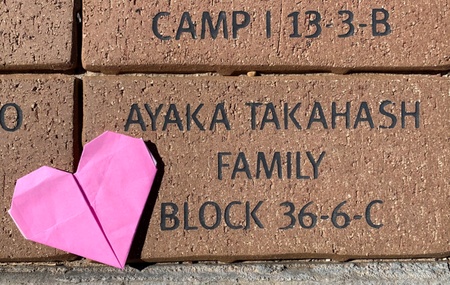

My mother, grandparents, aunts, and uncle lived in Block 36, just across the road from the elementary school. There are farm fields now where their barrack had been, but since it stood just two barracks in from the road, I can get closer to the site of my family’s former home than most Poston descendants can. I cross the road and stand on the edge of the field and turn around slowly. My 360-degree view reveals a wide expanse of sky, mountains rimming the valley, and flat farmland all around.

I asked my mother recently, “When you first got off the bus at Poston and looked around, how did you feel?” She replied, “It was a very strange feeling. Lost.” On my pilgrimage visit, I felt an echo of my mother’s feelings. Standing on the land at Poston, I, too, felt disoriented. Lost. Incapable of imagining in any coherent way the world that my mother lived in as a young teenager.

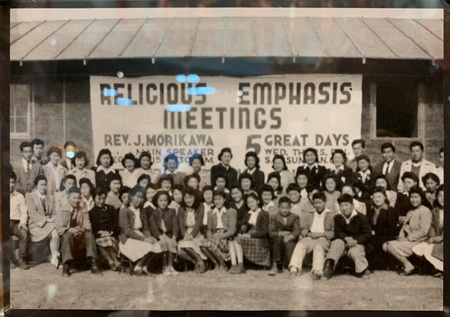

I know there were hundreds of barracks stretching out in every direction when my mother lived here, but try as I might, I can’t see in my mind’s eye what she would have seen. I am unable to map my mother’s memories, and even the knowledge from my own research about Poston, onto the landscape around me. I had studied the photos displayed at the pilgrimage and at the Colorado River Indian Tribes Museum, seeking scraps of information or flashes of insight. But the landscape I find myself in is too big, too empty, and too utterly changed for me to visualize where my mother walked and what she saw.

I realize that although my mother has been telling me about her experiences at Poston, in some sense they for me unknowable, ungraspable. And they are slipping farther back, receding and becoming fainter with the passage of time as the last witnesses disappear. But the dust, the Poston dust that my mother remembers so vividly, is real and tangible.

I cannot summon up an image of what my mother would have seen standing in front of her barrack, or walking to the school, or in the mess hall or the latrine. But the dust is still here. I see it, feel it, smell it, brush it off my clothes. It is the strongest physical link I have with my mother’s experiences.

I recently participated in the ceremony when the Ireicho – the book containing the names of the 125,284 people of Japanese ancestry confined during World War II – was installed at the Japanese American National Museum. We marched solemnly in procession, carrying 75 sotoba – wooden memorial tablets – representing the incarceration sites across the U.S. Affixed to each was a container holding earth, soil – dust – collected from that site. The ceremony recognized the symbolic power and the sacred meaning of that soil.

The dust holds meaning. It holds memories. The dust remains.

*This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on December 13, 2022.

© 2022 Janis Hirohama