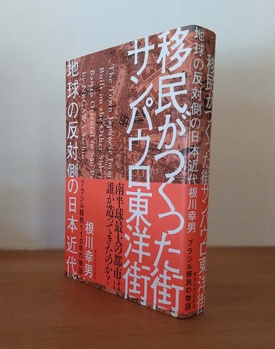

We spoke to Negawa Yukio, a special research fellow at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies and author of São Paulo Oriental Town: A Town Built by Immigrants: Modern Japan on the Other Side of the Earth (University of Tokyo Press, 2020), a book that focuses on the Japanese neighborhoods of São Paulo, Brazil , which make up the world's largest Japanese community. He talks about his research on immigration and the background to the creation of this book.

The appeal of "immigration" as an adventure story

--What first sparked your interest in immigration issues? And what prompted you to research the history of the Japanese community in Brazil?

Negawa : When I first visited Brazil to see the Carnival in 1992, I stayed at a pension in the Oriental district of São Paulo. There, I came into contact with many Japanese and Japanese-Brazilians living in Brazil, and I had a simple question: why did they and their ancestors come all the way to the other side of the world? I also met an elderly man named Mr. S. who had immigrated to Brazil before the war and worked as a cowboy (a ranch manager called Capatais) in a settlement called Bastos inland in São Paulo state (then a pioneering frontier), and I thought that was a cool way of life.

The man told me that when he was in junior high school, he saw a Hollywood movie and admired cowboys, so he bought his own land and immigrated to Brazil. At the time, I had the image of immigrants as people who struggled to make ends meet, so my stereotype was shattered when I heard Mr. S's story about his family's home being a village headman in Ehime Prefecture and his father being a prefectural assemblyman. As I listened to the life stories of immigrants, including Mr. S, I became very interested in immigrants to Brazil.

--Many people are researching the topic of immigration from various angles, but why do you think "immigration" generally attracts such researchers? What is your opinion?

Negawa : I think a big part of it is meeting fascinating people through research. In general, informants in migration research are people who have left their hometowns, traveled to foreign countries, experienced a variety of things, and overcome many problems, which makes them fascinating characters, like the protagonists of an adventure story.

Another benefit is that the micro-life histories of individuals and families can provide clues to unravel the reality and mechanisms of globalization. In particular, in research on modern times, when the global movement of people and goods is active, the presence of immigrants and the languages, cultures, and lifestyles they bring with them are factors that cannot be ignored in transforming policies and people's lives. With the annual international migration population approaching 300 million, and 3.5% of the world's population moving across borders and living in countries other than the one in which they were born, it would be reckless to think about the world without taking immigrants into consideration.

However, in addition to these research theories, there were many times when I felt elated while researching Japanese immigrants in Brazil. When asked why they emigrated, and why they settled in the remote areas on the frontier of development, many of the informants cited curiosity and a sense of adventure. Why do people cross the ocean? As in the case of Mr. S introduced earlier, one of the attractions of this study is that it gives a glimpse into the principles that motivate humans, which cannot be explained by push-pull theory alone.

Positivist research approach

--What is your basic approach to your research and investigation methods? You mentioned the achievements of Chicago School sociologists, but could you please explain this point in relation to your own research methods?

Negawa : I place importance on a positivist methodology that balances the methodology of documentary history through historical criticism based on documentary materials with the methodology of field science through fieldwork and interviews. In particular, the approach to urban inner cities and the method of participant observation were developed as part of Chicago School sociology, and Louis Worth's Ghetto, which depicts Jewish neighborhoods around the world, became a direct model for drawing the history of the Oriental neighborhoods.

However, I am not very smart, so I am not good at theorizing or abstracting. I am the type who gets by on my feet. Therefore, I value seeing and hearing things directly, and I value the connections I have made with people I have gotten to know. In addition to local and blood ties, I also trace networks of school and religious ties, such as school alumni associations, my husband's temple, and the church I attended, to investigate human relationships. I also place importance on walking around and seeing things with my own eyes when doing fieldwork.

I visit the same place a hundred times, or rather, if possible, I visit the same place many times, at different times and seasons. I used to live in the Oriental Quarter for about three and a half years, and even after I moved to Brasilia for work, whenever I came to São Paulo, I would stay at a hotel in the Oriental Quarter, hosted by the prefectural association, and walk around at different times of the day, morning, noon, and night, listening to people's stories. In the process, I have come into contact with countless people. As I wrote in "The Oriental Quarter of São Paulo, a Town Built by Immigrants," this book is built on the overlapping memories and stories of those people.

--In your book, you touch on Japanese emigration overseas and Japantowns around the world. Compared to these, what are the unique features of Japantowns in Brazil, such as Sao Paulo's Oriental Town?

Japanese Town is my second home

Negawa : I think it's the fact that it was built voluntarily by immigrants in the farthest place from Japan. In an era when air travel was not yet commonplace, the loneliness of Japanese immigrants in Brazil, located on the other side of the world, was unimaginable. After experiencing a painful war and conflicts of victory and defeat, when they decided to settle in Brazil permanently after the war, it was only natural that they wanted a second home, a Japanese town (a new home) to call their own. I think I can understand the feelings of the city's pioneers who built the large vermilion-painted torii gate in the middle of Galvão Bueno Street.

The appeal of Oriental Town is that it is a historical entity formed around a modern media transmission device, a movie theater, and also a living ethnic town. The COVID-19 lockdown caused a period of decline in visitors, but when I visited in August-September 2022, it had fully recovered, and it was so crowded with people and cars that it was impossible to walk on weekends, as it had been before.

Toyogai is where I first lived in Brazil for a few years in the late 1990s, and I have a special attachment to it as my "second home." When I revisit it after a while, I feel that it is still the same unsophisticated town, but at the same time, there are new shops and graffiti that I have never seen before, and I think that one of its charms is that it shows a new face amid the same things.

--I've heard that in the countries where Japanese people have emigrated overseas, there are still things that are more "Japanese" than in their home country of Japan. Can you tell us if you have noticed anything like that about things, actions, or ways of thinking in the Japanese community in Brazil?

Negawa : It depends on what you mean by "Japanese," but first I think of the expressions and phrases remaining in the Japanese language of Brazilian Japanese, known as colonialism. When I heard the words "book" and "hinoshi" (a tool used to smooth out wrinkles in cloth by placing a charcoal fire inside it) from a Sansei boy who seemed like a typical modern Brazilian, I didn't know what they meant at first.

Other things that come to mind are strong family (blood ties) and, especially in rural areas, the hospitality shown to guests is strong. When most Japanese immigrants lived in rural areas, they could not survive without family-based farming, with the head of the household at the center and the wife at the core, and cooperation. This strengthened these ties, and may still remain today. However, this may not be limited to Japanese people. The strength of family ties may also be due to the influence of Latin culture.

Transition and Diversification of Japanese Brazilians

--I think many Japanese descendants in South America, such as Brazil, have experience working in Japan, or have put down roots here. I've also heard that there is a generation called the "Lost Generation" who returned from Japan and suffered an identity crisis. There are many different types of Japanese descendants, but what is the current situation for Japanese descendants in Brazil?

Negawa : A period of transition and diversification - perhaps this sums it up in both a good and bad sense. Until around the 1950s, most Japanese and Japanese-Brazilians were agricultural immigrants, but there are examples of them switching to commerce relatively quickly. Until a certain point after the war, in cities there were ethnic occupations such as market merchants (feirantes), barbers, laundries, and Japanese restaurants, but now occupations and livelihoods have diversified. In terms of economic level, they cover the wealthy to the bottom, and they live all over Brazil, from the Amazon in the north to Rio Grande do Sul on the Argentine border in the south.

Although it is sometimes pointed out that the unifying power of the Japanese community has declined and that the third and fourth generation Japanese immigrants are becoming more detached from it, I don't think that the period during which the Japanese community was (incompletely) integrated around the Japanese Cultural Association lasted very long. Even if the emphasis is on either Brazil or Japan, it is becoming more common for transmigrants to travel between multiple countries and regions, and I think this is also tending to become a kind of identity.

I have relatives on my mother's side in Brazil, and among the third and fourth generation - my cousins' generation - some came to Japan to work and settled there, while others returned to start their own businesses. There are also some who graduated from graduate school in Spain and are working and raising their children in Barcelona. So, when asked if they plan to live in Japan or Spain forever, they say things like, "I want to go back to Brazil someday." Looking at my own family, we can say that the category of Nikkei people is expanding as they become more diverse, globalized, and mobile.

Witnessing this diversification of Japanese Brazilians, I feel that when I write books or papers, I always hesitate to refer to them as "Brazilian Japanese immigrants" or "Japanese Brazilians". I have written a book called "The History of Education of Japanese Immigrants in Brazil", but it was based on research on the states of São Paulo and northern Paraná, where Japanese immigrants were mainly concentrated. In terms of percentage, about 80% of the Japanese population lives in that area, but Japanese people are also distributed in the Amazon River basin, the northeast and the south. When I look at other researchers' papers, I often see titles like "Brazilian..." or "Brazilian..." that only investigate one region or a few places, but in the future, even if they are the same Japanese people or communities, I think more attention should be paid to regional characteristics.

--You say that there is still a lot to be written about the history of Japanese Americans who don't appear much in public, such as those who work in the nightlife district, as "another face of Japanese town." Could you please explain this a bit more? (I feel like these people aren't mentioned much in the history of the first generation in America either.)

Negawa : I don't drink alcohol myself, so I don't know much about the "nightlife." However, when I started living and visiting Brazil from the early 1990s to the late 1990s, there were quite a few nightclubs called boaches in and around Oriental Town. Oriental Town also had the character of a night entertainment town. The women who gathered at the establishments I was taken to were (as it seemed) all non-Japanese. However, as I continued my research, I found that up until the 1960s and 1970s, there were quite a few Japanese bars and nightclubs in operation, where many second- and third-generation girls worked for Japanese hostesses. Before karaoke was introduced, it was difficult to keep up with customers unless you spoke Japanese.

There was a rebellious journalist named Miura Saku who ran a Japan-Brazil newspaper before the war, and his wife was a former prostitute, and it is said that her son from a previous marriage was clearly of mixed race. There are not many records, but it is likely that among the immigrant women who came to the city from rural areas before the war, some, not just Japanese, worked in nightlife establishments, and in the 1930s, there were already several restaurants known as ryotei in the Conde neighborhood, where Japanese women competed for beauty. Both Conde and Oriental Town were located in the downtown area of the big city of São Paulo, so naturally they had this "nightlife face."

Speaking of nighttime impressions, I lived in a high-rise apartment at the bottom of a hill on San Joaquim Street in the Oriental Quarter, and when I looked out the window at night, I could see that São Paulo was pretty dark. But the Oriental Quarter was lit up with lily-of-the-valley lights, and the city center was pretty bright even at night. I thought that was quite impressive. An organization called ACAL (the Liberdade Chamber of Commerce, a Japanese-Brazilian business and industrial association) worked with the city police to put a lot of effort into maintaining public order. If public safety was poor, there would be no business.

There are also bars where local shopkeepers gather to drink, and I think future research on immigration and ethnic towns will need to draw attention to the "nightlife" of these cities.

--The transformation of the São Paulo Oriental Town, which is steeped in Japanese yet Brazilian culture, is fascinating. How do you think the Oriental Town will change in the future?

Negawa : As I wrote in the magazine " Japanese Folklore ," when the city of São Paulo was locked down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, events in the Oriental Town, such as the Tanabata Festival and New Year's parties, were held online, and restaurants focused on online ordering and delivery. This strategy of adapting to the new normal required the cooperation of the young digital generation, encouraging their participation.

J-POP, which was popular around the 2000s, has been completely replaced by K-POP in Japan, but it seems that there are still many core fans in parts of Brazil, which I think is interesting from a cultural circumlocution perspective.

When I visited Brazil in August and September last year, I was surprised to see that Toyo Town had regained all its vitality. New stores that seemed to cater to J-POP fans, which I hadn't seen the last time, had opened. However, Toyo Town has a spatial limit to how much it can develop, so I imagine that the Japanese Cultural Association, ACAL, and each prefectural association will develop in the direction of using digital media to expand their networks and hold events.

A mysterious town where you can see the past and the near future

--After reading your book, I want to visit the Oriental Quarter of São Paulo. Please tell us about the charms of this town.

Negawa : Yoshikazu Tanaka, one of the pioneers of the Oriental Town, is said to have been inspired by Asakusa when he created the Galvão Bueno shopping district, the predecessor of Oriental Town. As I described in "A Town Built by Immigrants," this town developed around a Japanese movie theater from the 1950s to the 1970s. After the war, many people gathered in Liberdade in search of entertainment to watch Japanese films, and more and more stores opened targeting these audiences, eventually forming a shopping district.

Both the movie theater and the shopping street are now in the world of Showa retro. Even in Japan, it is rare to find a shopping street so crowded with shoppers that you can't walk through it, but if you go to Toyo-gai, you can experience the atmosphere of a nostalgic shopping street. However, the people walking around are a very multi-ethnic mix...

Before the Japanese shopping district was built, Galvão Bueno Street was a quiet residential area, and some two-story Portuguese-style buildings called sobrados still remain. The Oriental Quarter is built on top of these many layers of history (with the paint peeling off in places).

A mix of Showa retro and colonial styles, with torii gates, lily of the valley lanterns, and signs in kanji and katakana, the streets are teeming with people of multiple ethnicities, including not only Asians but also Europeans, Africans, and a mixture of these. Toyogai has a mysterious charm that makes it seem like a place from a bygone era and the near future at the same time.

INTERVIEWER Could you tell us what kind of research you have planned on immigrants and Japanese people in the future?

Negawa : I am currently working on a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research project on the global migration of modern Japanese people, particularly the memories and experiences of people on immigrant ship voyages. Rather than focusing on people living on land in sending and receiving countries (regions), as has been the case in traditional immigration histories, I am focusing on the third phase of migration, the seas, rivers, ships, and sea routes.

I also want to consciously conduct research on the Japanese community in the Amazon, an area that has been under-researched in my own research. Conventional research has said that Japanese immigrant ship experiences go from Kobe to Santos, but prewar Amazonian immigrants would disembark in Rio de Janeiro, change ships, go to Belém at the mouth of the Amazon, change ships again to enter a tributary, then change to a smaller riverboat called a gaiola, and after several days of travel, finally reach the settlement by canoe.

Another example of postwar immigration is the case of the Quinari colony in Acre in 1958. They had to change ships three times upstream from Belem to Bocca da Acre, and after about four months from Kobe, they finally reached Rio Branco, the capital of Acre. They were already at the end of the world. I think it was the longest voyage ever made by a group of Japanese immigrants. During this long voyage, Japanese immigrants experienced rough seas and seasickness, contact with foreigners (white and black), discrimination and special treatment, observed rare landscapes, customs, food, plants and animals, and sometimes contracted measles or cholera, and their values and worldview were transformed by their experiences on the voyage.

In Japan, research on immigration history has focused on immigrants' home villages, sending countries and receiving countries/regions, that is, immigrants while they are on land, but I want to focus on the process, that is, the period of time immigrants spend on the ship. Although it is only a few dozen days to a few months in the decades-long life of immigrants, it is an unforgettable memory for the immigrants. It seems that in many cases, the networks (relationships between fellow shipmates) that were built on the ship continued long after they arrived in Brazil.

The development of Toyo Town required the publicity and cooperation of Japanese newspapers, and it is said that Mizumoto Tsuyoshi, the founding figure of Toyo Town, and Mizumoto Mitsuto, president of the São Paulo Newspaper, were fellow passengers on the same immigrant ship. It is also believed that the performances by prefectures at the "Oriental Festival" and "Tanabata Festival," two of Toyo Town's four major events, are an extension of the entertainment shows that were held on immigrant ships. The first generation of Issei who founded Toyo Town, including Tanaka Yoshikazu and Mizumoto Tsuyoshi, all traveled to Brazil on immigrant ships.

Jacques Attali, one of the most prominent intellectuals and historians of modern Europe, points out in his book "The History of the Sea" that all important events in world history have taken place at sea, and the history of migration seen from the sea can also teach us a lot.

Negawa Sachio : Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1963. Graduated from the Graduate School of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo. PhD (SOKENDAI). Specialized in transplanted people history, maritime history and cultural studies. After serving as an associate professor at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Brasilia, Negawa Sachio is currently a special researcher at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. He is also a lecturer at Doshisha University and the University of Shiga Prefecture. Major publications: Reprint of "Umi" Vols. 1-14 (Kashiwa Shobo, 2018, supervision and commentary), A History of Education of Japanese Immigrants in Brazil (Misuzu Shobo, 2016), A History of Education of Japanese Immigrants Crossing Borders: A Perspective on Multicultural Experiences (Minerva Shobo, 2016. Co-edited and co-authored with Inoue Shoichi), Cinquentenario da Presenca Nipo-Brasileira em Brasilia (FEANBRA, 2008, co-author) |

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai