In recent decades, Asian-born performers have occupied a visible place in western classical music. These Musicians From a Different Shore, in scholar Mari Yoshihara’s phrase, have included renowned soloists such as Yo-Yo Ma, Mitsuko Uchida, Cho-Liang Lin, Midori, Kyung-Wah Chung, and Lang Lang, conductors such as Seiji Ozawa and Myung-whun Chung, as well as countless top-flight ensemble players.

In contrast, the presence and contribution of Asian classical music performers in the period before World War II has remained surprisingly obscure. In fact, a number of Japanese-born performers, including singers Miura Tamaki and Hizi Koyke, and xylophone virtuoso Yoichi Hiraoka, starred in North America during that period, even as numerous American-born Japanese performed to acclaim in Europe.

One outstanding transnational Japanese performer was Yoshinori Matsuyama, who made a name for himself in music across three different continents. On two occasions in his career, at the outset and towards the end, he made successful tours in the United States.

Details on Matsuyama’s life from available sources are scanty and contradictory. He was born in Kagoshima—most accounts say 1891, but others indicate 1892, 1894, 1896, or 1889—and was the son of a violinist. He attended Tokyo Music School. At first he played violin, then decided to study singing. When he was not permitted to change his major, he quit school, and later left for the United States.

In June 1916, after stopping in Honolulu, Matsuyama arrived in San Francisco. According to one account, he settled in nearby Berkeley. One day he heard beautiful piano music coming from a mansion near the UC Berkeley campus, and decided to offer himself as a houseboy there. The owners of the house quickly discovered Matsuyama’s beautiful voice, and recommended him to a local white promoter. Wherever the truth lies, he embarked on a singing career. The Nichibei Shinbun recorded him as giving a concert at the Buddhist church Kinmon Gakuen in San Francisco in December 1916, which included selections in Italian, English, and Japanese.

Matsuyama proceeded to make up a vaudeville act. Billed as “Prince Matsuyama” and “The Japanese Caruso,” he toured the vaudeville circuit. In August 1916, he played the Pantages Theaters in Seattle and Vancouver, Canada, In Vancouver, he wowed the audience by singing French songs, then performing an aria from Verdi's Rigoletto in Japanese.

In March 1917 he opened at the Hippodrome in San Diego with a program of opera arias and popular songs. The Evening Tribune praised his performance: “He was in excellent voice and his numbers were well-selected. The audience clamored for more after each number and the singer was forced to respond with several encores.” San Diego Union added that, “he was given close to an ovation.”

Three weeks later, Matsuyama opened at the Strand in Portland, Oregon. The Oregonian (perhaps mistaking him for a more seasoned performer), stated “Yosinori Matsuyama (sic), already a favorite with vaudeville patrons who remember his previous successful appearances, presents a repertory of operatic and classical songs. His fine, strong tenor is very attractive and something unusual in the line of oriental voices.”

After Portland, Matsuyama toured Idaho and Montana, before arriving in Salt Lake City in August. There he played the Liberty theater, and wowed the critics. The Salt Lake Telegram gushed: “Yoshinori Matsuyama, the celebrated Tokio Enrico Caruso, has a wonderful voice and caused a lot of wonderment in the pleasant manner in which he presented his songs.” The Salt Lake Herald-Republican also raved: “It is rare that the public is privileged to hear a Japanese with such a wonderful voice as Matsuyama’s.”

Not to be outdone, the critic from the Salt Lake Telegram repeated the praise of Matsuyama’s voice and added, “To miss hearing this brown-skinned lad from the Orient would be missing one of the big vaudeville treats of the year.” Matsuyama went on from Utah to Wyoming, where he played the New Atlas Theater in Cheyenne.

Soon after, Matsuyama moved to New York. There, with financial support from the eminent scientist Dr. Jokichi Takamine, he pursued studies at the Stevens School of Music, first with the soprano Evelina Hartz, then Percy Rector Stephens—considered a top-notch vocal coach. His draft card, dated June 1918, lists him as residing on West 123rd St. in Harlem and as “not regularly employed.”

Still, Matsuyama joined in performance in his new hometown. In April 1918 he appeared at the Greenwich Village Theater as part of a dance recital by the modern dancer Michio Ito (also performing was the pioneering Japanese classical musician and comoposer Kosaku Yamada, who was spending two years in the United States). Ito, then at the start of his career, performed the Nō drama The Hawk’s Well, adapted from the Japanese by William Butler Yeats. Matsuyama sang poems from the text. It apparently was a popular performance, as they repeated it for the doll festival holiday at Webster Hall.

In July Matsuyama and Ito did a benefit performance for Josephine Osborn’s wartime charity Free Milk for France. A few weeks later they did another benefit performance for the charity, this time at the Club des Vingts in Washington DC.

During this same time, Matsuyama appeared in vaudeville in New York (on a program headlined by tperformance of a play, The Splendid Sinner, with opera star Mary Garden in a non-singing role.) “Mephisto,” a critic for Musical America, reviewed Matsuyama’s performance:

“He has a pleasing tenor voice, of good quality, sings with a certain tendency to nasal tone production, which is common to the Japanese...However he sings with fine musicianly understanding, and so pleased the audience that, after his first number he was called out again and again.”

The critic added that an audience member had remarked that, in addition to his talent, Matsuyama’s fine elocution and clear understanding of the feeling of the song pointed to his having fine teachers. “Mephisto” concluded, “The young Japanese is destined to success, and in the course of time he will be a prominent feature of the concert stage, for in addition to the novelty of his appearance, his personality is pleasing because of his good nature and his modest, unassuming character.”

Despite such positive press, Matsuyama does not seem to have found other engagements. Whether for financial or cultural reasons, he decided to migrate to Europe. In November 1918, shortly after the Armistice made Atlantic travel once again safe, Matsuyama sailed for Liverpool.

According to one account, he entertained allied troops in France as part of the Y.M.C.A. Military Entertainment Corps. What is certain is that by September 1919 he was in England, playing on a bill at the Hippodrome in Manchester, then Bristol in November. In December 1919 he performed at a reception at Claridge’s Hotel organized by the Japan Society which was attended by the Duke of Connaught (a son of Queen Victoria) and Lord Balfour.

The following month, he performed in a variety show at the Coliseum theatre in Charing Cross, where he was billed as “Matsuyama, the phenomenal Japanese tenor.” The British theatrical magazine The Stage complained that Matsuyama “has a voice of excellent quality which he uses in three numbers which must be rather hackneyed to music hall audiences,” and advised him to choose less familiar songs. Matsuyama later alluded to his poverty during his time in England, and mentioned that both he and Yoshie Fujiwara, another aspiring Japanese tenor, made use of the same pawnbroker to get money during their slack periods.

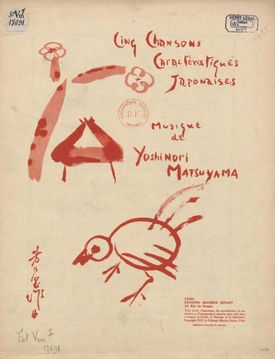

In 1920 Matsuyama moved to Italy, where he studied opera in Milan and in Naples. By the beginning of 1922, he was in Paris. There he made his name, not only as a performer, but as a composer of the song cycle “5 chansons caractéristiques japonaises” (5 typically Japanese songs)1. This piece, made up of “Lullaby,” “Fisherman’s Song,” “Love Song”, “ Yedo (Tokyo) Song,” and “Sakura (Cherry Song),” featured Japanese texts by the composer, plus his French translations for three of the songs (French writers Denise Donio and Isabelle Mallet translated the others). Matsuyama even produced the Japanese-style artwork for the initial published score.

The French newspaper Le Menstral described the premiere of the composition and the “precise and ardent talent” of the young Japanese musician.

“On the piano could be seen a manuscript which, painter at the same time as a musician, this artist had adorned with colors and shapes, thus visually prolonging the popular melodies that he collected and transcribed, careful not to let go anything of the original inspiration. In addition to a magnificent talent as a singer, Mr. Yoshinori has, in addition, the power of inspiration within these precious pages. In a voice that is by turns penetrating, then as if shrouded in shadow, he slips into the minds of listeners the melancholy or joy of his Five Japanese Melodies.”

Later that year, Matsuyama performed again in Paris at the Théâtre des Nouveautés, alongside the dancer Sakai Ashida. This time Le Menestral’s critic was even more provocative:

“The unfortunate musical critics cannot be everywhere at once: detained at the concert of the Orchestre Philharmonique de Paris, all I was able to hear was the compositions of Mr. Yoshinori Matsuyama, Japanese tenor, who with the assistance of the dancer Ashida offered tableaux accompanied by singing. Mr. Yoshinori Matsuyama’s art is extremely dramatic and evocative, and he mimed and sang his last scene with a very moving intensity of pain. As for the music, very simple in line, it is of curious and refined harmony.”

At the outset of the following year, Matsuyama again performed for French audiences. In February he appeared at the Theatre de St. Lo and sang a program of which the first half consisted of Japanese songs, including his own, and the second part of European songs. In April 1923, he performed in Lyon in the series called Les Heures. A critic wrote:

“Les Heures presented on Sunday some Japanese works and artists with special qualities who have received a warm welcome in France. The composer Yoshinori Matsuyama sang his own works, delicate romances with an evocative sweetness, using a high voice that was flexible and infinitely captivating.”

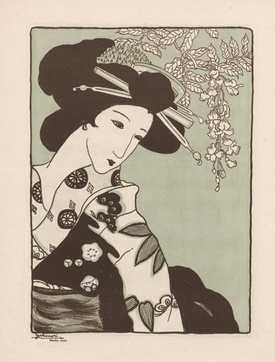

In early 1923 Matsuyama joined forces with again with Ashida and another Japanese dancer, Toshi Komori, to present Les Estampes Vivantes Japonaises (Living Japanese prints) at the Theatre des Champs Elyssés. The show consisted of a series of “tableaux vivants” choreographed to resemble Japanese prints (a widely popular art form among the French). The Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf praised his singing of his own works such as “La Complainte du Mendiant” (“The Beggar’s Complaint”) and the “Chanson d’amour”.

In September 1923 Matsuyama played the well-known concert hall L’Olympia as part of a gala performance to raise money for Japan following the great Kanto earthquake. In August 1924 Matsuyama joined with other Japanese performers to put on a costume ball, the Fête à Tokio, organized by Paul Tissier.

By this time, Matsuyama was known at least as much for his composing as his singing. As early as February 1923, the singer Olenine d’Alheim included Matsuyama’s song in her recital program. More importantly, the pioneering African-American tenor Roland Hayes adopted Matsuyama’s “Sad Song” and “Sakura” song as part of his standard concert programme, with which he toured North America and Europe. When he presented Matsuyama’s songs at a concert at London’s Wigmore Hall in April 1923, a critic for the Daily Telegraph referred to the songs as “charming exotics in which the East of musical convention is given something of a new aspect.”

In June 1923, a French critic lauded Hayes for singing Matsuyama’s song plus five negro spirituals, all of which were “full in turn of humor and melancholy.” In December, Hayes sang “Sakura” as an encore at his Town Hall debut recital. He also included it in the program of his recital at Symphony Hall, Boston, the following year. (Hayes would again include “Sakura,” as well as a set of Chinese songs, on his program when he returned to New York in 1929 for his well-publicized recital at Carnegie Hall.)

Note:

1. A performance of the song cycle can be heard here: “Yoshinori Matsuyama Cinq chansons caractéristiques japonaises”

© 2022 Greg Robinson