In the 1930s, the women of the Ichioka family in Los Angeles excelled in multiple walks of life, including medicine and the performing arts. The brightest light among them was Toshia Mori, who became one of the first Japanese Americans to shine in Hollywood during the sound era. Sadly, the family’s relations degenerated into divisions and ultimately protracted legal conflict.

The head of the family was the physician and surgeon Dr. Toshio Ichioka. Born Toshio Sato in Hiroshima, Japan on February 3, 1884, he attended medical school at Tokyo University. When his bankrupt family was unable to further support his medical studies, he married Masako Ichioka, the niece and adopted heir of Dr. Genjun Ichioka.

The Ichiokas were a distinguished clan that had produced 16 successive generations of physicians. Through such a “muko-yoshi marriage,” Toshio Sato adopted the family name Ichioka and became joint heir with his wife. He thereby received funds to complete medical school and open a medical practice.

In the following years, Toshio and Masako Ichioka had four daughters. Toshio emigrated to the United States in 1917 and pursued studies at USC to obtain a California medical license. Masako and their four daughters arrived in 1920.

Upon receiving his California medical license in 1921, Dr. Ichioka opened a medical office in Little Tokyo. His practice reflected an idealistic view of the profession, as he treated ethnic Japanese, Filipino, and Mexican farm workers, laborers and domestics, most of them impoverished. For years, he regularly advertised in the Spanish-language dailies El Heraldo De Mexico and La Opinion.

Activist Karl Yoneda later described how, during the Great Depression, Dr. Ichioka offered free medical care to members of the local Japanese Unemployed Council. Yoneda recalled that the doctor told him, “I do not agree with your ideas, but I admire your efforts and courage, and this applies to all of your friends.”

In 1937, with four other Japanese doctors, he opened the Ichioka Clinic in Boyle Heights to provide low-cost medical care. Thanks to Ichioka family money and to his investments in real estate and businesses, Dr. Toshio Ichioka amassed a significant fortune. In 1930, his net worth was a reported $50,000.

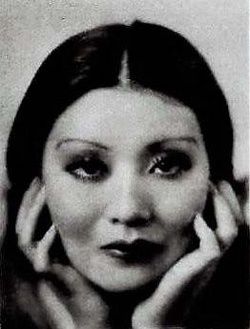

The doctor’s eldest daughter, who became Toshia Mori, was born Toshiye Ichioka in Kyoto, Japan on January 1, 1912. Once settled in Los Angeles, she attended the Theodore Kosloff Imperial Ballet School, with the goal of becoming a dancer. However, when she saw a performance by opera singer Maria Jeritza, she resolved on a stage career.

In 1926, the young Toshiye Ichioka broke into the movies as an extra for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer at $10 a week (her weekly salary fee ultimately rose to $175). She also appeared in an Emory Johnson film, The Non-Stop Flight, at Universal Studios. Her first break came when she performed (under the name “Toshia Ichioka”) in the MGM silent picture Mr. Wu (1927). The film, which starred Lon Chaney and Renee Adoree in yellowface roles, and featured Anna May Wong, was a tragedy of interracial love in China. Ichioka later said that the producers had planned to offer her the female lead, but decided that she was too young to play love scenes convincingly, and therefore assigned her a secondary role.

Her work nonetheless attracted notice, and she won small roles in the films Streets of Shanghai (1927) and The Man Without a Face (1928). Dissatisfied with these roles, however, Ichioka left Hollywood and accompanied her mother Masako and sisters to Japan, arriving in April 1928. Within weeks, Masako died of peritonitis.

Toshiye was signed by a Japanese studio, and she played the leading role in the film Eikan (AKA The Crown of Glory), portraying a Viscount’s daughter. Curiously, she wore American clothes for the role.

By 1930, the young actress had returned to Hollywood, at the dawn of the sound film era, and adopted the screen name Toshia Mori. During 1930-31 she appeared as an extra in Way for a Sailor, Reaching for the Moon, and Ambassador Bill, but was not enthused over the roles or her compensation. Interviewed by the Los Angeles Times in September 1930 while working as a cigarette seller at the Blossom Room of the Roosevelt Hotel, she declared that she saw more future in the business world than the cinema.

However, in 1931 she made an independent comedy short with Slim Summerville, Peeking in Peking (a role originally designed for Nisei performer Iris Yamaoka) and had walk-ons in the films Union Depot and Roar of the Dragon. Newspaper articles announced that she had been signed as the female lead in the The Honorable Mr. Wong, starring Edward G. Robinson as a Chinese assassin. However, the final film, renamed The Hatchet Man, starred Loretta Young in yellowface, and Mori was relegated to a brief part as a secretary, Miss Ling. Similarly, she was touted for the title role in Paramount Pictures’ Madame Butterfly, opposite Cary Grant, but the role eventually went to Sylvia Sidney in yellowface.

Mori’s first important sound film was The Secrets of Wu Sin (1932). an independent film set in San Francisco Chinatown. It told the story of a white woman journalist investigating a smuggling ring involving the illegal immigration of Chinese workers. Mori played Miao Lin, the lover of Richard Loo’s central character Charlie San.

Around this time, Mori signed an extended contract with Columbia Pictures. The studio may have hoped that she would be their answer to Anna May Wong. Columbia executives selected her as their WAMPAS (Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers) Baby Star—the only non-white person ever so honored. Lillian Miles was the studio’s original choice, but she was not going to be present to receive the award, as required, so Mori was substituted.

While being named a WAMPAS star was considered quite an achievement, as presaging “future stardom,” in fact among that year’s winners only Ginger Rogers and Gloria Stuart would go on to notable careers. (A cringeworthy surviving clip from the Hollywood on Parade film series features appearances by Mori and other WAMPAS stars. When Mori is described by the hosts as a “piece of Dresden china,” she exclaims in unaccented English, “No, I’m not Chinese, I’m Japanese,” and her host responds, in stereotyped Asian tones, “Oh, excuse please.”)

Soon after, Mori had her biggest break when she was cast in the Columbia film The Bitter Tea of General Yen, adapted from a novel by Grace Zaring Stone and helmed by the renowned director Frank Capra. Mori played the part (originally conceived for Anna May Wong) of Mah-Li, the favorite concubine of the titular character General Yen, portrayed by actor Nils Asther in yellowface. Mah-Li receives the General’s gifts of luxury and precious jade, only to betray him by her clandestine love for Yen’s close adviser Captain Li. For her infidelity, Mah-Li is sentenced to death, but is saved through the intervention of the American missionary Megan Davis (Barbara Stanwyk), a hostage at General Yen’s court with whom the General has fallen in love. Mah-Li ultimately turns on her benefactors.The movie was not a great financial success, though it achieved a certain historic status as the first film ever to play New York’s Radio City Music Hall. Mori gained plaudits for her performance, including from TIME magazine, whose critic noted: “The most noteworthy female member of the cast is Toshia Mori, a sloe-eyed Japanese girl whom director Frank Capra…hired for the part of the ex-mistress.” Capra himself referred to Mah-Li in a Los Angeles Times interview as “the best Chinese role for a woman in the history of the screen.”

After Bitter Tea and the favorable WAMPAS publicity, the studio quickly cast Mori in a succession of pictures. The first one was Blondie Johnson (1933), starring Joan Blondell as a woman who takes over an underworld gang by using her brains. It was a rare gangster film of the era that had a woman as the central character. Mori plays Lulu, a mobster of indeterminate “oriental” heritage who is a friend and roommate of the heroine.

The same year, she starred in Fury of the Jungle, a film set in the fictional Brazilian Amazon town of Malango. Mori portrays Chita, the town’s only woman resident, whom all the town’s men desire. When a white American woman, Jean, arrives in town with her sick brother, the townsmen fall for her, including Chita’s son Taggart. In a fit of jealous fury, Chita betrays Taggart to the police to punish him for his interest in Jean. Although Chita is described as a “half-breed,” making her Mori’s only explicitly non-Asian role, the Bismarck Tribune affirmed that as Chita “Toshia Mori has an Oriental glamour distinctly her own.”

In February 1934, Mori married a fellow Asian-American actor, Allen Jung. Soon after, under her new name Toshia Mori Jung, she made a cameo appearance in the movie The Painted Veil, as a dancer in a stage tableau. She then dropped largely from sight, as she sought to break her contract with Columbia Pictures.

In 1935, she had a small role as a telephone operator in the Universal Pictures thriller Chinatown Squad. Although she was formally uncredited, a Philadelphia Inquirer noted that “Toshia Mori does very well in a ‘bit’ part.”

In 1936 the actress made a screen comeback of sorts under the name Shia Jung—the Chinese pseudonym perhaps responding to growing anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. As Shia Jung, she appeared in the movie Charlie Chan at the Circus (starring actor Werner Oland in yellowface as the title character). As the wise-cracking circus contortionist Su Toy, the sight of whom enthralls “number one son” Keye Luke, she gained favorable reviews, sufficient for her to be cast the following year in a second film, Charlie Chan on Broadway (this time once again under the name Toshia Mori). As Ling Tse, sexpot employee of the Hottentot Club, she again romances Keye Luke’s character.

In 1939, again as Shia Jung, she appeared in the independent film Port of Hate. Set on a mythical island in the South Seas, it revolves around the discovery of valuable black pearls and a struggle over their ownership. Variety magazine gushed that as Bo Chang, “Shia Jung, an Oriental, is excellent and has a chance for the future.” Despite the Variety critic’s prediction, Port of Hate would prove to be her last motion picture.

In 1939 Mori joined the staff of Robert Ripley’s syndicated column “Believe it or Not” as a research assistant, and moved to the New York area. In 1940 and 1941, she took trips to the Caribbean. In a 1946 article, columnist John S. Van Gilder described being given a tour of Robert Ripley’s summer estate in suburban New York by “Chinese charmer Ming Jung”—the former actress Toshia Jung—who showed him Ripley’s prize Chinese junk boat.

She and Allen Jung were divorced in 1942. Soon after, she married Norman Ehret, a young man 13 years her junior, and the two settled in New York City. In 1954 Toshiye Ehret was granted US citizenship. Throughout this period, she turned to writing. In 1941, under the name Toshia Mori Jung, she took out copyright on two plays, Bitter Blues and The last Supper. In 1959, as Toshia Ehret, she copyrighted The Guiding Spirit of Mrs. O’Blaney, a teleplay in three acts. None of the scripts appear to have ever been produced.

Toshiye Ehret died on November 26, 1995 in New York. By then, Toshia Mori had been largely forgotten. Her story was a marvel of perverse timing: she immigrated to the United States, began acting as a teenager, then experienced a brief but active period of Hollywood glory in the 1930s.

Alas, like Anna May Wong, she discovered that studio executives were largely unwilling to award meaningful roles to Asian women, and she retired from films in her mid-twenties. In one sense, this was the most generous stroke of timing for Mori: by leaving Hollywood and migrating to the East Coast, she escaped the government dragnet after Executive Order 9066.

© 2022 Greg Robinson