Lilly Krohn, of Laconia, Indiana on most sunny days could be seen working out in her garden or taking care of her yard, enjoying some of Southern Indiana’s beauty at the same time. She moved forward in life keeping focus on all the positives and the many blessings she had been given. Lilly was from a different generation, one that has rapidly dwindled every day to very few survivors, the World War II generation. This is a generation of people who countless times have taken their personal untold and sometimes painful experiences with them when they leave us, never fully told.

When Lilly—a proud Japanese American woman—recalled the war, one single day 77 years ago was etched in her memory forever. Though painful, one day every year she gave herself permission to privately look back on those events of that day, one that endlessly changed her life and the course of history. Now, she has allowed me to share her deepest memories and thoughts of what occurred on August 6, 1945, and the days ahead, as she witnessed it.

* * * * *

The United States entered WWII on December 8, 1941, a day after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor. In just a few short hours this airstrike created a temporary weakened country. However, it also created one sea-to-sea undisputed purpose to declare war and defeat the Empire of Japan. Subsequently, in solidarity to Japan, Germany, and Italy declared war on the U.S., we began a war already rapidly escalating on two fronts, in Europe and the Pacific.

Fast-forward four years to the spring of 1945, Italy and Germany had surrendered though the war against Japan still waged on. The U.S. had advanced to the Japanese mainland resorting to an intense air raid campaign directed at multiple cities including Tokyo, in hopes of winning the war. In late July, an ultimatum was issued to Japan by the Allies demanding an unconditional surrender of all armed forces or face prompt and utter destruction; however, the request was rejected.

President Truman strongly contemplating a decision to invade Japan, in hopes of finally forcing a surrender, knew heavy loss of American lives would occur to ensure victory. There was an ongoing death toll that was already insurmountable. The president did have one additional though untested option against any enemy: a new element of modern technology that could kill thousands instantly.

The Manhattan Project, headed by the U.S. military, was a 2-billion-dollar research and development project of an atomic weapon that had just been completed in July 1945. Officials believed this new nuclear constructed weapon of uranium, if utilized correctly, had the capability alone to cripple Japan to the point of surrender. The President wrestled over the moral dilemma of using this form of weaponry, very aware of the high loss of Japanese civilian life it would bring. Finally, hoping to bring the war’s end one step closer, a decision was made to drop the bomb; however, a particular place of detonation had to be chosen first.

Japan is the largest archipelago country in East Asia and consists of thousands of islands, although geographically notable for five main ones. On the island of Honshu, the country’s biggest, sits the city of Hiroshima slightly above sea-level on its southeast tip. Hiroshima, meaning wide island in Japanese, was built on a scattering of islands eventually consisting of 82 bridges. It comprised of scenic coastline beauty resting in the delta of the Ota River and its six separate branches.

A little over a decade prior to WWII, thousands of miles away the U.S. was approaching the Great Depression while Japan’s economy was stable; this was positively affecting Hiroshima’s flourishment. This initial castle and small fishing town had grown into a major urban center. It had a vibrant downtown shopping area, as well as an industry hub incorporated with the opening of the Mazda automobile plant in 1931. Further, Hiroshima’s seaport had become a key center in Asian shipping.

* * * * *

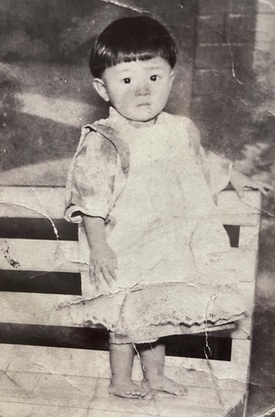

Rewinding back 15 years prior to the beginning of WWII, Lilly Krohn was born Yuriko Ishigaki in Hiroshima, Japan on February 3, 1924, to father Matajiro Ishigaki and mother Mineko Fujimoto Ishigaki. She was the oldest sibling of brother Yoshio and two sisters Taeko and Yoko. Tragically, Lilly’s third younger sister passed away from an illness while just a toddler.

Matajiro, mostly recognized for his considerate and caring manner toward others, had an extremely outgoing side as well. He started Kendo Sword Company, a successful bamboo martial arts equipment business in town, learning his influential business skills from his mother, a businesswoman herself. He presented a sociable business reputation spending numerous hours out having drinks and dinner amongst current and potential clients.

Mineko, a homemaker like many women at the time, was known for her quiet and sweet manner along with some shyness. In addition, she was descended from a pre- 20th century high ranking Japanese social class and of ruling military nobility, the Samurai warriors. Hence, Lilly’s upbringing was traditionally and financially different than most of that time period; historically, the Samurai worked for the feudal lord who, along with the military dictators, held most of the political power in Japan.

Lilly reflected on endless fond memories growing up living mostly alongside her tight knit maternal relatives, though she admitted being especially sheltered to her surroundings by family and the customary Japanese way of life. In the fall of 1931, Japan invaded and controlled the northwest Chinese province of Manchuria. This forced subsequent battles that in time led to the start of the Second Sino-Japanese war in the summer of 1937, initiating a precursor to WWII.

Lilly, still a young girl at the time and obviously not very political or aware of the surrounding world, knew little of what was occurring. Since her family did not speak on the matter at all, the Japanese form of public news came from newspaper and radio updates always relayed in a filtered positive spun format. Lilly remembered no detailed information was provided; just the words, Japan Wins, was always written in the headlines or broadcasted for citizens to see and hear.

Lilly thought back to her time as a 13-year-old girl living in Hiroshima when she first started to notice real changes. Germany had already begun an early informal alliance mostly of mutual land interests with Japan, and their country’s soldiers started to be witnessed in town. American music became forbidden, although citizens were allowed to listen to German music on the radio—predominately symphony. During this time, the city was building up a sizeable installation of soldiers and military supplies apart from becoming an important military communication command center. Similarly, it was a metropolis of manufacturing parts for planes, bombs, and rifles.

Lilly, in her opinion, was deluded by a Japanese plan of secrecy as the 1939 beginning of the war in Europe followed by the attack on Pearl Harbor all went off in silence. She recalled no broadcast heard, newspaper headline read, or any citizens speaking of the events. A draft soon ensued after the Pearl Harbor attack, giving all indications of a major military buildup in direction of war and it continued, lastly drafting her younger brother.

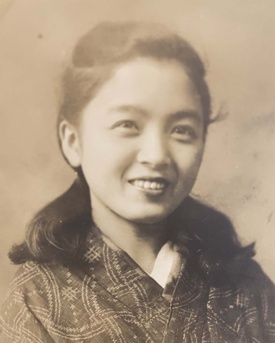

As WWII continued growing rapidly closer to Japan’s borders, Lilly sought a normal life as much as possible. Now at the age of 21, she was hired to be a typist at the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall. It was a dome building primarily used for arts and educational exhibitions, and was part of the downtown’s main business district.

Her attempt at a conventional life drastically changed. As she described that Sunday evening of August 5, 1945, she witnessed an unforeseen site of U.S. planes overhead. That evening radio broadcasting stopped and the alarms sounded, therefore causing Lilly and other citizens to anxiously take refuge in a shelter. This continued most of the night until the sirens were at last dismissed around midnight local time. The planes were determined to be reconnaissance.

Hiroshima, comprised of a population of around 350,000 residents, was one of the few bigger Japanese cities left that had not been hit by major air raids in the course of the war, so concern was always present. Additionally, the city had become familiar to Japan’s allies, as it was home to Japan’s 2nd Army headquarters and housing thousands of infantry soldiers, alongside a strong military shipping position. Civilian accounts tell of seeing off numerous troops chanting the Japanese loud battle cry, Banzai, leaving the harbor eager to enter the Pacific. Also, fearing a military land invasion, Imperial Army troops backed by a strong readied civilian militia were prepared to defend the islands until their demise if forced. Hospital nurses practiced using bamboo spears against stuffed dummy enemies to defend against any possible hospital takeover.

Lilly looked back on seeing no leaflets dropped urging citizens to flee, although there have been conflicting reports that leaflets were dropped by U.S. planes. Plus, it was reported that the Japanese government did order an evacuation to the countryside in fear of some form of serious attack, reducing the city’s population by thousands.

What was unknown to Japan’s military at 2:45 a.m., just hours before daybreak on that August 6th Monday morning, was that a B-29 bomber plane, Enola Gay, had lifted off the ground 1,500 miles away. The majority of the 12-man crew was not aware of the true mission that was to take place; even so, they knew cyanide tablets were on board in case of its failure.

Japanese radar detected that was unknown at the time: three weather reconnaissance planes were approaching from the southern part of Japan at 7:15 a.m. This led to requiring an issued alert and stopping all radio broadcasting in many cities, including Hiroshima. One of the planes of this first set of three, a lead up named Straight Flush, was now flying over Hiroshima with an immense hole opening in the clouds. It sent a short-coded radio message back to the slowly approaching Enola Gay and two additional planes that read: Cloud cover less than 3/10 at all altitudes. Advice: Bomb primary.

The bomber, backdropped by a blue sky of perfect visibility released the safety switches at 7:45. Approaching nearly 8:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the plane formation coming in was probably not more than three planes and the air raid alert was lifted, determining the planes to be on continued reconnaissance.

Thirteen minutes later, the approaching Enola Gay escorted by instrument and photography planes are now fully detected. However, it was too late because at 8:15, a ten-foot in length, 9,700 lb. self-detonation atomic bomb—codenamed Little Boy—dropped from a large ceiling clasp of the Enola Gay at 31,000 ft through the bomb bay doors partnered by parachute in trail.

That morning, the citizens of Hiroshima were going about their normal routines of shopping at the downtown marketplace and starting their normal workday. Lilly was to start at 8:00 a.m. and living less than two miles away, she normally commuted by riding her bicycle. She had an extremely strict boss focused on proper work ethic, so being on time and no allowed work breaks were standard Japanese practices he firmly enforced. The night before, as the result of a flat tire, she had taken her bicycle down to the shop for repairs. She arranged to pick it up the following afternoon.

Planning to ride the streetcar to work the next morning, Lilly mistakenly overslept to 8:00 a.m. and still moving slowly, her mother scolded her to hurry. Now rushing, she swiftly made her way to open the front door…except she was interrupted by a bright reddish-orange flash of light that filled the side window. Then seconds later succeeding an earsplitting roar, their home’s windows burst ensued by the ceiling and walls crumbling down.

© 2022 Jon Stroud