In the last chapter, I introduced some articles on people’s expectations for Japanese Consulate. This time, I will talk about some articles on the opening of Seattle Route and Seattle Route and the transcontinental railroad around 1918.

OPENING OF THE SEATTLE ROUTE

Nippon Yusen Kaisha’s (NYK Shipping’s) Seattle Route opened in 1896, connecting Seattle and Yokohama. The opening of the route triggered a rapid increase in the number of Nikkei immigrants to Seattle.

In the January 1, 1910 issue of The North American Post, Seiichi Nakase, who was vice president of the Seattle sub-branch of Nippon Yusen, commented on the opening of the Seattle Route, looking back on the old days.

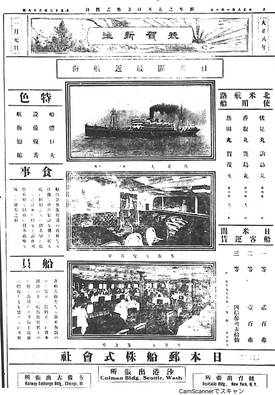

“City of Seattle and NYK” (From the Jan. 1, 1920 issue)

About 20 years ago, when railroad king James J. Hill was extending the Great Northern Railway to Seattle, he received a piece of advice from an influential Chicago entrepreneur, James Bray Griffith: ‘We will need to work in partnership with Japanese marine transportation businesses in the future.’ It was then decided that Mr. Hill would go to Japan to look into that possibility. At the time, Yusen Kaisha was deciding where to lay its route to the U.S. With Mr. Hill’s input and the possibility of future US-Japan trading business, Seattle was chosen. In 1896, Miike-maru, a ship that weighed no more than 3,000 tons, opened up the route for the first time.

The opening of the Seattle Shipping Route connected Seattle to the transcontinental railroad system, which boosted the development of Seattle.

THE SEATTLE ROUTE AND GREAT NORTHERN RAILROAD

Six ships are recorded to have traveled the Seattle Route around 1918: Fushimi-maru, Suwa-maru, Katori-maru, Kahima-maru, Atsuta-maru, and Kamo-maru. These ships regularly traveled between Seattle and Yokohama about every three weeks.

In January 1918, a series of articles describe how Aimaro Sato (Japanese ambassador to the U.S., 1916-1918) traveled from New York on the Great Northern railroad, boarded Fushimi-maru in Seattle and returned home.

“Ambassador Sato Trapped in Snow” (From the Jan. 14, 1918 issue)

The train that carried Ambassador Sato on the Milwaukee Line in Chicago was forced to halt near the state of Ohio, due to snowfall. The train has been already delayed for 20 hours now... According to the incoming telegram from the Chicago sub-branch of Nippon Yusen, Ambassador Sato left Chicago on the evening of the 14th and was expected to arrive in Seattle on the night of the 17th assuming there would be no mechanical trouble on the train. For the past few days, however, there has been a blizzard east of the Rockies. Since no train can move west at the moment, we cannot expect the regular arrival of any train. In any case, (Sato) will not make the scheduled sailing of Fushimi-maru on the 17th, yet we have not heard about it being postponed to the 19th.

“Ambassador Sato Passing Through” (From the Spokane Branch, the Jan. 18, 1918 issue)

Ambassador Sato’s train got to Spokane at 5 p.m. on the 17th, arriving behind schedule. After a brief stop, the train left for Seattle late in the night. As none of the (Spokane) Japanese residents knew of the ambassador’s arrival, Mr. Sato stayed inside the train until 8 p.m.

“Ambassador Sato’s Long-Awaited Arrival” (From Jan. 18, 1918 issue)

The train carrying Ambassador Sato reached Seattle at 9 a.m. on the 18th, a few hours behind schedule. Consul Matsunaga, Secretary Takeuchi, two chairpersons of Nihonjin-kai (Japanese Association)—Takahashi and Okuda, Nakase(NYK), a secretary from Nakamura Jitsugyo (Business) Club, Suzuki from Tohokujin-kai (Northern Honshu Assn.), and Secretary Nakajima (Nihonjin-kai) welcomed him at the station.

Ambassador Sato slowly got off the train with his attendants. He shook hands with everyone and expressed his gratitude, saying “Thank you for coming to meet me.”

He finally seemed to feel at ease. “As our train got delayed, I learned the lesson that we can’t rely on the schedule.” He then was led to Hotel Washington.

This good-natured gentleman willingly told me (the reporter) about his experience, as I bothered him at the hotel while he was resting.

“I’ve never had such an insane experience like this. We were already late by 48 hours en route. Since I heard that the sailing of Fushimi-maru was moved up to the 17th, I was so anxious but there was nothing I could do about it in the snow. They made sure that the train was constantly heated, so I was able to survive the cold. Also, everyone was so good to me.”

“The (Afternoon) Banquet” (From the Jan. 18, 1918 issue)

At noon on the 18th, a banquet was hosted by Consul Matsunaga at Washington Hotel. With Ambassador Sato as a guest of honor, Takahashi, Okuda, Ishida and Nakase represented the Japanese (community) side, and on the Caucasian side were the heads of the Chamber of Commerce, Mr. Rose and Mr. Roman, and 23 other well-known people... From 6:30 p.m., Ambassador Sato attended a dinner party hosted by the Jitsugyo Club and spent time with many fellow Japanese residents.

Like Ambassador Sato, prominent figures from Japan at the time frequently visited Seattle. Japanese residents held a welcome party with great hospitality each time such a figure arrived.

“Fushimi-maru Leaves Seattle” (From the Jan. 19, 1918 issue)

Fushimi-maru left for Japan on the afternoon of the 19th, later than the scheduled time of 2 p.m. Ambassador Sato took his attendants and boarded a little after 9 (a.m.). The security was heightened at the wharf as usual where they prohibited any entry other than passengers, and Consul Matsunaga was the only one who was allowed to board. Ambassador Sato left a message of gratitude with the Consul that he was truly grateful for the warm welcome by the Japanese residents in Seattle. There were about 30 passengers in the first-class cabin, and the total number of passengers from the second and third-class cabins was 200-plus. Heiji Okuda, members of his jitsugyo group of home-country observers, Tamotsu Nakatani—the chief manager of Ban Shoten (store) in Portland—and others were present too.

The December 18, 1917 issue reported that Heiji Okuda gathered the Seattle home country observers and took a 10-day sightseeing trip to Japan in a group of about 15 members on Fushimi-maru, which was scheduled to depart in January of the following year.

The January 17, 1918 issue listed the names of these observers, and Toru Aoki from Shibata Shoten, Manpei Miyagawa and his wife from the hotel industry, assistant manager Sentaro Ito from Nihon Boeki (Japan Trading), and others boarded Fushimi-maru.

The January 18, 1918 issue published a comment of Tamotsu Nakatani who was the manager of Ban Shoten, a giant retail store in Portland, Oregon, from his talk with a reporter of The North American Times who was visiting the store’s Seattle branch at the time. Nakatani was on Fushimi-maru with his family on his way back home.

“The development in Seattle over the past year or two has been astonishing, and the way they organize all businesses is something we cannot help feeling envious of, as our peers in Portland could learn a lot from it. For Ban Shoten, too, we were a little late in opening a branch in Seattle. I believe that the outcome would have been more significant had we opened it a year earlier.”

As we can see, Consul Sato and many Japanese residents in Seattle boarded Fushimi-maru to go to Japan, but they would have had to wait until February 7 for Kashima-maru if they had missed the ship. This shows that Seattle Route and the transcontinental railroad were such important means of transportation connecting Japan to Seattle.

In the next chapter, I will introduce articles about the development of Seattle Route following the year 1919.

Reference:

Kaigai Ryoko Annai-sha (Foreign travel guide), Beikoku ryokou annai (Travel Guide to the U.S.), 1927.

Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku Seihokubu Nihon Imin-shi (History of Japanese Immigrants in the Northwestern United States), Taihoku Nippo-sha, 1929.

Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha, eds. Nihon Yusen 50 nenshi (50 Years History of Nippon Yusen), 1935.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. This article was originally publishd on May 14, 2022 in The North American Post and is expanded for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Ikuo Shinmasu