The first Japanese immigrants arrived in Peru as contract workers for the coastal plantations. It was a limited and temporary move, sponsored by the governments of both countries.

But as so often happens, reality takes over and changes one’s plans. The Japanese immigrants left the plantations, either as their contracts expired or fleeing the abuses they suffered there. Most settled in Lima and established their own businesses.

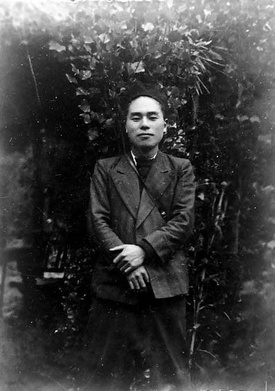

Others traveled out to the provinces of Peru, with the most adventurous making their way to the jungle or to Cuzco. One of those was Michika Kawamura, who left Arequipa in 1938 and settled in the mythical capital of the Inca empire, where he worked at a family member’s business.

PRESIDENT TO THE END

Michika Kawamura put down roots in Cuzco. He started a family, opened his own business and served as president of the Japanese Peruvian Association in the región.

Michika Kawamura’s life story has been carefully reconstructed with personal and family memories by his grandson Enrique Kawamura, a tourism guide and writer.

Michika settled in Cusco the year before World War II broke out. Like many Japanese immigrants in Peru, he was considered part of the “enemy camp” and was forced to hide from the authorities. He sought refuge in the “dense thicket” of the jungle, his grandson says. That was around 1941.

Having survived that dark period during the war, Michika carved out an existence in a land that he made his own, and where he spent the rest of his life.

He moved to Cuzco to work, but it could have been a temporary stop. Why did he choose to stay, why did he find it so appealing?

Enrique says it could be for the same reason that any foreigner would decide to settle there: “Cuzco has a mystery and charm that makes people from other places fall in love with this city”.

Cuzco attracts people who want to connect with themselves and with nature, which is something hard to find in big cities, he adds.

“He found his destiny here”, he says of his grandfather.

Although Michika eventually felt like a Cuzco local (even changing his name to Marcial), his ties to Japan never weakened or disappeared. On the contrary.

Enrique recalls that his grandfather served as a kind of Japanese ambassador in Cuzco. He hosted Japanese visitors to the city and even invited them to stay at his home.

He also played a key role in the founding of the Japanese Peruvian Association in Cuzco and led the organization for several years.

Michika was a very sociable and friendly person who valued being part of a brotherhood, a strongly rooted tradition in Peru.

Owner of an ice cream shop, his social circle transcended the business realm. He belonged to several associations and was a friend to artists, filmmakers, and photographers, including the legendary Martín Chambi.

Like any good Japanese man —according to his grandson— he liked to fish in lakes, lagoons and the Vilcanota River.

As he aged, he maintained his institutional and cultural ties, and upon his death in 1996, he was the honorary president of the Japanese Peruvian Association.

ASSEMBLING A PUZZLE

Enrique Kawamura is dedicated to collecting and preserving the history of Japanese immigrants in Cuzco.

Along with another Nikkei from Cuzco, visual artist Harumi Suenaga, he is putting together a book of photographs of established Cuzco families of Japanese origin, including the Kawamuras and the Suenagas.

With the help of friends, relatives, social media and notices in traditional media outlets, Enrique and Harumi have steadily collected images, despite interruptions caused by the pandemic. They expect to have the results this year, with the publication of their book.

Along with the Kawamuras and the Suenagas (owners of a company with more than 60 years of experience in the automotive sector), the families that are featured include the Nouchis (whose patriarch was the first mayor of Machu Picchu), the Nishiyamas (a well-known family of photographers), the Inugais, the Omuras, the Motohashis, and the Iwakis.

The book also has a timeline and captions that provide a context for the photographs, guiding the reader through a history of Japanese immigrants and their descendants in Cuzco.

Although they haven’t located all the families they sought out (some no longer live in Cuzco), in general the reaction from the community has been positive. “Fortune is smiling on us”, says Enrique, alluding to the large volume of material and the support they have received from Nikkei families in Cuzco.

Having completed the collection phase of the project, they are now immersed in digitizing the photos.

“It’s a big commitment”, Enrique says of the responsibility they have taken on with this project, which has two aims: to recognize the Issei and pay homage to the pioneers, and to pass on their testimony so that future Nikkei generations will know who they were.

“We’re knitting together something beautiful”, he says.

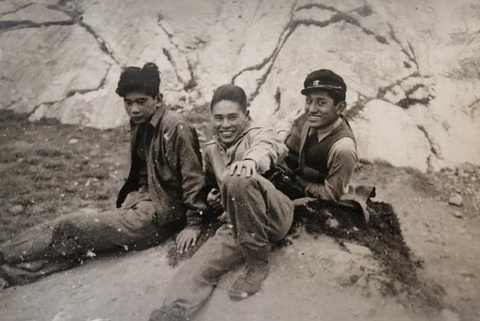

Their research has turned up some meaningful surprises. For example, Enrique found his grandfather Michika in photographs belonging to other Nikkei families.

Enrique says that even his own aunt —Michika’s daughter— was surprised that her father appeared in images she had never seen.

Thanks to these happy coincidences, they feel that this project is like putting together a kind of puzzle.

“I love that there is order within the chaos”, Enrique says. “Everything is coming together in a harmonious way, that’s the most wonderful part”.

Enrique and Harumi don’t have to wait for the harvest to enjoy the fruits of their work, since the process itself provides a great deal of satisfaction. “It’s an effort that is full of surprises rather than a research project, and we’ve encountered many joyful moments along the way”, he says.

So why did they embark on this adventure?

According to Enrique, both of them are committed to preserving the culture of their ancestors. Harumi does this through her art, while he expresses it in various ways through his essays and novels.

“We’re following an instinctive drive that might be related to our DNA”, Enrique explains. “We’re answering the call of our ancestors”.

Enrique has always been attracted to the spirituality and traditions of Japan’s millennial cultural heritage.

For this ex dekasegi, who lived in Japan for eight years, the book of photographs is the latest milestone in his career as a researcher, permanently linked to his grandfather’s country. History and affection come together in a project that, if everything goes well, will become reality this year.

© 2022 Enrique Higa Sakuda