In the fall of 1941 as relations worsened between the U.S. and Japan, and war became imminent, the presence of 110,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast pushed the issue of internment to the forefront. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to know where their allegiances stood in the event of a war and tasked John Franklin Carter, the head of his newly-formed White House intelligence and “fact finding” operation with the assignment. Carter tapped his lead agent Curtis B. Munson to get answers. The question over loyalties and internment was a ticking time bomb.

* * * * *

From October 1941 to January 1942 secret memos passed between Munson, Carter and Roosevelt assessing the situation on the West Coast. Although a similar investigation was already afoot under the auspices of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), Roosevelt, who was known for supplementing intelligence information, sourced the job to Carter who selected from his “cadre of agents,” Curtis B. Munson. The wealthy Chicago businessman operated under the guise of being a government official.

SEARCH FOR LOYALTY

Munson spent four weeks traveling to San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle then another nine days in Hawaii in search of loyalty. Throughout this time Roosevelt received regular updates from Carter along with Munson’s field notes. Early in the investigation on October 19, Munson wrote: “The Japanese, citizen or alien, will be quiet whether they sympathize with Japan or not. Undoubtedly by far the largest bulk – say 90% – like our way of life best. The Japs here, especially the citizen, is straining every nerve to show their loyalty to the U.S. The Japs here are in more danger from us than we from them.”

Almost two months into the investigations, Pearl Harbor was attacked. The December 7th bombing left 2,403 Americans dead. The nation was feeling vulnerable and also suspicious of their Japanese American neighbors who looked like the enemy. On December 8, Roosevelt delivered his “day of infamy speech” and declared war on the Empire of Japan.

Shortly thereafter in a December 20th report, Munson noted, “Your reporter, fully believing that his original reports are still good after the attack, makes the following observations about handling the Japanese ‘problem’ on the West Coast.” What followed were seven pages of suggestions for how “loyal Japanese citizens should be encouraged.” The Japanese Americans were on the same side as their fellow Americans, but the push for internment continued to gain momentum.

Words of caution from Assistant Attorney General James H. Rowe, Jr. did nothing to change the course of events. On February 2, Rowe wrote to Roosevelt’s personal secretary Grace Tully,“Please tell the President to keep his eye on the Japanese situation in California… There is tremendous public pressure to move all of them out of California – citizens and aliens – and no one seems to worry about how or to where. There are about 125,000 of them, and if that happens, it will be one of the great mass exoduses of history...”

On February 19, 1942 Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the evacuation and internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of them citizens by birth.

THE MUNSON MEMOS

By the time Roosevelt issued the order, Munson had produced copious amounts of material which established the loyalties of the Japanese Americans. The proof was in the President’s hands, and still he signed. “...the enormity of this incredible governmental hoax cannot begin to be fathomed without taking into consideration the definitive loyal findings of Curtis B. Munson...” wrote Michi Nishiura Weglyn in Years of Infamy, The Untold story of America’s Concentration Camps.

“Apart from occasional brief references to the Munson Report in works of scholarly research, the eye-opening loyalty findings of Curtis B. Munson have yet to receive merited exposure in the pages of history,” noted Weglyn in her 1976 book. Munson’s work was the primary source of information on the loyalty issue leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor. His memos bear witness to this dark period of history, as do the scars from internment.

The Munson Memos are a record of a tumultuous time. In October 1941 Carter began informing Roosevelt about Munson’s progress, “...The essence of what he has to report is that, to date, he has found no evidence of which would indicate that there is danger of wide-spread anti-American activities among this population group. He feels that the Japanese are more in danger from the whites than the other way around...”

REPORT TO ROOSEVELT

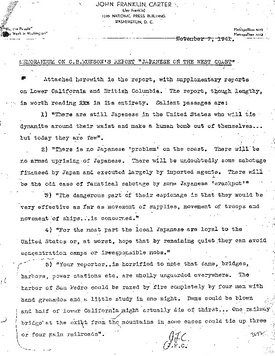

Over the next three months from October 1941 to January 1942, Carter kept Roosevelt apprised of Munson’s ongoing investigations. On October 29, Carter sent Roosevelt a memo confirming there was no indication of any anti-American activities in Western States, “Subsequent reports from Curtis Munson still confirm the general picture of non-alarmism already reported to you. Munson’s 25-page report on his West Coast investigation noted, “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the coast...” and “For the most part, the local Japanese are loyal to the United States...”

On December 19, Carter wrote to Roosevelt, “Curtis Munson reports from Los Angeles that already five L.A. Japanese-Americans have committed suicide because their honor could not stand the suspicion of their loyalty. He is rushing to Washington for a program, which is based largely on the O.N.I. (Commander Ringle) proposals for maintaining the loyalty of Japanese-Americans and establishing wholesome race-relations. Its essence is to utilize Japanese filial piety as hostage for good behavior.” The first point stated: “Encourage the Nisei (American-born Japanese) by a statement from high authority.”

After three months of investigations, Munson had answered the question and Roosevelt had his answer. The country’s Japanese Americans would be loyal.

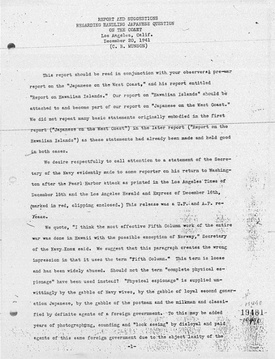

THE RINGLE REPORT

Where the Munson Report ended, the Ringle Report picked up. On January 26, 1942, the Chief of Naval Operations, requested a report from Lieutenant Commander Kenneth D. Ringle “concerning his views on Japanese” after learning Munson stated in his December 20, 1941 report that "your observer must note without fear or favor that 99% of the most intelligent views on the Japanese, by military, official and civil contacts in Honolulu and the mainland, was best crystallized by two intelligence men before the outbreak of the war. These two men are Lieutenant Commander K.D. Ringle of the 11th Naval District in Los Angeles and Mr. Shivers in Honolulu of the F.B.I."

Ringle, an ONI officer who had been looking into the loyalty issue since July 1940, was well ensconced in the Japanese communities. He had also assisted Munson in his investigation by introducing him to some of his Nisei contacts within the Japanese communities. Ringle noted in his report, “...a very great many of the Nisei have taken legal steps… to officially divest themselves of Japanese citizenship… even though by doing so they become legally dead in the eye of the Japanese law.”

The Ringle Report was submitted on January 30, 1942 and strongly advocated against mass confinement of the Japanese Americans. Ringle noted, “That, in short, the entire ‘Japanese Problem’ has been magnified out of its true proportion, largely because of the physical characteristics of the people; that it is no more serious than the problems of the German, Italian, and Communistic portions of the United States population, and finally that it should be handled on the basis of the individual, regardless of citizenship, and not on a racial basis.”

INTERNMENT INEVITABLE

On February 19, “one of the great mass exoduses of history” became a reality. The Executive Order handed over power to the War Department to take control. It authorized the Secretary of War Stimson to establish “military areas” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.”

The language used in the edict by the three architects of the order, Western Defense Commander John L. DeWitt, army strategist Major Karl R. Bendetsen, and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, was vague and never specifically stated Japanese, but they were clearly the intended persons. California considered anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese lineage as sufficient to be interned. Bendetsen, went so far as saying anyone with "one drop of Japanese blood" qualified.

On March 29, 1942, under the authority of Executive Order 9066, DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 4 which began the forced evacuation and detention of West Coast residents of Japanese-American ancestry on a 48-hour notice. The forced relocation was swift and without mercy. At the start, 17 temporary assembly centers were established at racetracks, fairgrounds, in Washington, Oregon, California and Arizona. By November 1942, the relocation was complete with ten centers in remote areas in 6 western states and Arkansas: Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Tule Lake and Manzanar in California, Topaz in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Granada in Colorado, Minidoka in Idaho, Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas. The evacuees lost their personal liberties, homes and property.

In contrast, in Hawaii, where some 160,000 Japanese Americans lived, by war's end, only 2,000 people of Japanese ancestry from Hawaii were interned. Their military governor, Lieutenant General Delos Emmons, resisted mass internment. In a radio broadcast soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Emmons assured Japanese Americans: “There is no intention or desire on the part of the federal authorities to operate mass concentration camps. No person, be he citizen or alien, need worry, provided he is not connected with subversive elements. While we have been subjected to a serious attack by a ruthless and treacherous enemy, we must remember that this is America and we must do things the American way. We must distinguish between loyalty and disloyalty among our people.”

Eventually there were legal challenges by Japanese Americans in 1943 and 1944. However, the cases of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui were all lost due to information that was suppressed by U.S. Solicitor General Charles Fahy, who said all U.S. government and military assessments were in favor of internment. Almost 40 years later, justice was served. In 1981, researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga discovered the only remaining “Final Report on Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast” which stated that intelligence sources agreed Japanese Americans posed no threat. All reports were thought to have been destroyed. This information helped overturn all three convictions.

In 1985 Edward Ennis, a former Justice Department attorney, testified in the coram nobis hearing of Hirabayashi. A June 21, 1985 New York Times article, “Suppression of Evidence in 1943 Cited” reported that, “The Government suppressed evidence when it argued in 1943 that the Supreme Court should uphold the conviction of a Japanese-American citizen...Mr. Ennis… cited a report by Lieut. Cmdr. Kenneth Ringle of the Office of Naval Intelligence indicating that the Japanese-American espionage problem had been magnified out of proportion...A memorandum to Mr. Fahy, written by Mr. Ennis in 1943 and introduced in court today, said that excluding this information from the presentation to the Supreme Court ''might approximate the suppression of evidence...”

Hirabayashi’s exclusion and curfew convictions were overturned in 1986 and 1987 respectively. Korematsu’s case was overturned in 1983 and Yasui’s conviction was overturned in 1986. In 2011 U.S. Solicitor General Neal Katyal wrote a public repudiation of Fahy’s actions.

THERE WAS NOTHING TO FEAR

The tragedy of internment was that the true threat was fear. It was what Roosevelt had warned about in his 1933 inaugural speech when he said… “This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honesty facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory...”

Back in 1933 Roosevelt’s words empowered the nation to get back on its feet after the Depression. In December 1941 the country was reeling from tragedy and paranoia was rampant. Those same words could have been used to combat racism and internment. What if Roosevelt had told the nation there was nothing to fear from their fellow Japanese Americans? Perhaps Roosevelt should have borrowed Emmons words, “We must remember that this is America and we must do things the American way.”

In December 1944, two and a half years after signing Executive Order 9066, Roosevelt suspended the order. On February 17, 1976 the order was terminated by proclamation. In 1982 the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) issued its final report, Personal Justice Denied, stating that the internment was motivated by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. It also reported “that not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage or fifth column activity was committed by an American citizen of Japanese ancestry or by a resident Japanese alien on the West Coast.” In 1988 Congress offered an apology and individual reparations of $20,000 to surviving Japanese Americans who had been wrongfully interned.

December 7, 1941 and February 19, 1942 will both live on in infamy as tragedies in American history. A total of 2,403 Americans died during the attack on Pearl Harbor. A total of 1,862 Japanese-Americans died in the internment camps. The causes of death differed, but they all died on American soil, all victims of war. They were all Americans.

© 2022 Susan Zimmerman