Two Nisei whose lives and career paths were strikingly uncommon were the siblings Miwa and Yoshio Kai. Miwa was a musical prodigy who starred as a classical pianist on the international stage in the years before World War II, then devoted herself afterwards to work as a skilled librarian—all of which no doubt included calling for quiet! Yoshio’s career was less spectacular than his sister’s, but he amassed a record of quiet heroism while in Asia during World War II, then built a solid life and career in the United States after the war.

Although they had very different life histories, Miwa and Yoshio Kai had many points in common. Both were well read, articulate, and interested in the arts. Most importantly, they each mastered English as well as Japanese. In the case of both siblings, these linguistic skills would prove to be decisive in their lives and career paths.

Both Kais were born in San Francisco. They were descended from Orie Kai, an early student of Yukichi Fukuzawa (future founder of Keio University). After working as a manager of the New York branch of a trading company that imported silk and tea, Orie Kai established the firm of O. Kai & Co. in 1885, and opened Japanese art and curio stores in San Francisco and New York.

Orie’s son Eiichiro studied English and French as a young man in Japan, and then moved into the study of Japanese calligraphy and painting as well as Western art. In 1897, Eiichiro moved to San Francisco and enrolled at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, then three years later took a tour of Europe to further his art studies.

In 1901 Orie Kai dispatched Eiichiro to run the San Francisco branch of O. Kai & Co. (At first, the branch was located on Kearny Street, but when the building was destroyed during the great 1906 earthquake, the Kai family then set up shop on Grant Avenue in Chinatown). Eiichiro Kai made a trip to Japan in 1905, likely in search of a wife, and returned to San Francisco with his bride, Ine [Ineko]. In the next years, the couple had four children, including Yoshio (born in 1907) and Miwa [Miwako] (born in 1913).

In the early 1920s, following Orie Kai’s death, Eiichiro and Ine decided to close the San Francisco store and return to Japan, where he would inherit Orie’s business interests. Once back in Japan, Eiichiro did not find a fortune waiting for him. Instead, he found employment managing a branch location of the Shirokiya Department Store.

Both Yoshio and Miwa accompanied their parents to Japan. Indeed, according to a family story, the two were together in Tokyo at the time of the 1923 Kanto earthquake—Yoshio grabbed his sister and carried her out of the house to safety. Once arrived in his new country, Yoshio, who had attended English-language schools and who had been a star schoolyard tennis player in San Francisco, was tutored intensively in Japanese language in order that he could take qualifying tests to enter middle school. He spent three years in school in Japan.

However, after he turned eighteen, his mother asked him to switch to night school, so that he could work during the day to supplement family finances and help pay tuition for his younger siblings. Bcause of his biligual skills, Yoshio soon found a job working for the Imperial Household Agency as a clerk and assistant waiter.

After taking courses in Gregg shorthand through the Extension Division of UC Berkeley, Yoshio was hired as a stenographer for the Merck Pharmaceutical company. Some time later, he advanced to the position of Secretary to the managing director of the Japanese branch of the Victor Talking Machine Company.

During this time, Yoshio moonlighted as a teacher of shorthand at a YMCA night school. One of his students was a woman named Hatsuko, the daughter of a plantation worker from Hawaii. Yoshio soon began seeing Hatsuko outside class.

In 1937, Yoshio was hired to work as an interpreter for American engineers helping build a plant at the Manchukuo Machine Works in Mukden. Yoshio’s mother Ine tried to persuade Yoshio to let her arrange a marriage for him to a well-born Japanese woman. Instead, Yoshio married Hatsuko in Dairen, and she moved with him to Mukden. There they had three children, of whom two died at a young age.

Ironically, even after World War II started, and there were no further American engineers employed in Japanese Mukden, Yoshio Kai’s skill as an interpreter led his employers to press him into service. Unlike his youngest brother Koji, Yoshio was not drafted into the Army during the war. Instead, because of his skills in English, Yoshio was charged with coordinating the labor of American POWs held at a local prison camp who were sent to work as slave laborers at the factory.

The POWs experienced harsh treatment, suffering cold, hunger, beatings, and fatigue--and according to some witnesses, forced participation in germ warfare experiments. Yoshio Kai showed humanity to the prisoners. He secretly brought them blankets, procured them vegetables for their soup, and saved them from violence by brutal guards. He also did not report the fact that the prisoners deliberately sabotaged equipment that they were given, though he was aware of it. Many prisoners later credited him with helping them survive.

Following V-J Day in 1945, anarchy reigned in Manchuria. As the Japanese troops that had peviously controlled the region abandoned the city of Mukden, Chinese Communist troops entered, followed by Russian troops who engaged in widespread looting and rape. Hatsuko was attacked in her home by two Red Army soldiers, but the soldiers fled following the arrival of Wayne Miller, an American POW factory laborer whose life Yoshio had previously saved.

Still, the Kai family was unable to leave Mukden, as they lacked valid U.S. passports and other required credentials. With the assistance of several former POW's who wrote letters of support to the US government, a passport was finally issued for Yoshio, Hatsuko, and their son Kenneth—their sole surviving child—and the family was able to leave in June 1947. After changing ships in Shanghai, they boarded a U.S. transport ship, and arrived in Honolulu on July 9, 1947. While in Hawaii, they were housed in barracks at Hickam Field.

Yoshio Kai and his family threw themselves into their new lives in America. In their first years back in the United States, they had two more children, Susan (Sachiko) and George. Nonetheless, they devoted themselves to caring for Yoshio’s family.

Eiichiro and Ine had survived the war, but like all Japanese suffered from continued scarcity of food and material goods—in desperation, Eiichiro was reduced to selling the family samurai sword in order to raise money to survive. Yoshio’s brother Koji, a veteran of the Japanese Army, had contracted tuberculosis and remained disabled. In order to help the family out, Yoshio sent half his earnings to the family in Japan. Once back in the United States, Yoshio reestablished close ties with his sister Miwa.

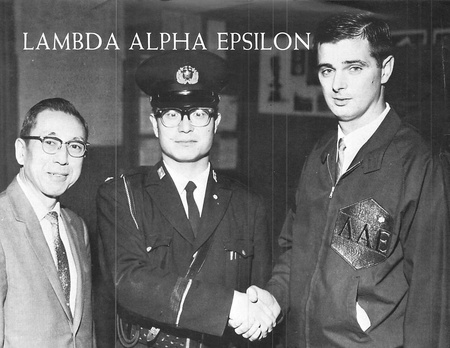

Following the war, Yoshio Kai lived in Hawaii briefly, before moving to Fresno, California. There he was employed as a deputy sheriff for 24 years. During his tenure in Fresno, he interacted on various occasions with counterparts in Japan, learning about differences in police tactics.

In an article entitled “A Neighbor Drops In,” published in The Sheriff’s Review in 1967, Yoshio described the visit of Sergeant Kazumitsu Naito of the Yamanishi Police headquarters. Yoshio’s article demonstrated both a penetrating understanding of police work and a fine English prose style.

Yoshio was also active in community work. Most notably, in 1977, in coordination with the Central California JACL Council, he conducted a survey of Issei in Fresno and their needs. Yoshio reported that the chief problem identified by local Issei was loneliness and isolation, and he recommended that the Issei Service Center remain in place, so that community members could meet up and spend time with fellow Issei. The survey also resulted in the establishment of a hot meals program for 35 elderly Japanese Americans in Fresno.

Following his retirement, Yoshio moved to San Jose. In later years, Yoshio also served as a resource for historians of the American POW experience in Manchuria. He died in San Jose in 2004.

Author's note: I wish to offer a shoutout to Dr. Kenneth Kai and to Susan Kai Hirabayashi, who graciously provided information on their father Yoshio Kai and their aunt Miwa Kai, and corrected some errors in my research.

© 2022 Greg Robinson