Throughout the postwar years, Reverend Kitagawa remained in Minneapolis, where he maintained an active voice in local affairs as an expert on race relations while working for the Federal Council of Churches. In February 1946, Professor Frank Rarig of the University of Minnesota interviewed Reverend Kitagawa for a local Minneapolis radio station. During the interview, Kitagawa referenced forced removal of Japanese Americans, stating that the community had faced wrongful persecution, but he praised the members’ successful adjustment to their new lives in Minneapolis.

In February 1948, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune quoted Kitagawa and three other religious leaders in support of President Truman’s civil rights program. Kitagawa commented specifically on the necessity for evacuation claims legislation to help alleviate the financial struggles of Japanese American families.

Kitagawa also regularly worked with the state government. In January 1949, Reverend Kitagawa authored a report for Minnesota Governor Luther Youngdahl’s Interracial Commission on Japanese American resettlement in Minnesota, as part of a larger report on Asian Americans in Minnesota.

While the report received widespread praise, a letter to the editor in the February 12, 1949 issue of the Pacific Citizen criticized Kitagawa’s characterization of Japanese Americans who had left Minnesota to return to California as being enchanted by “materialistic California psychology.” The author noted that Kitagawa’s report was more aimed at pleasing the people of Minnesota than explaining why Nisei wanted to return to California.

Kitagawa reiterated his support of resettlement in an article for The Presbyterian Outlook from February 1951. After summarizing the status of Japanese Americans in the postwar years, Kitagawa took a positive tone towards resettlement – one that would become popular in the years before the Redress movement – by extolling the importance of Japanese Americans leaving the West Coast and living in the heartland of the U.S.

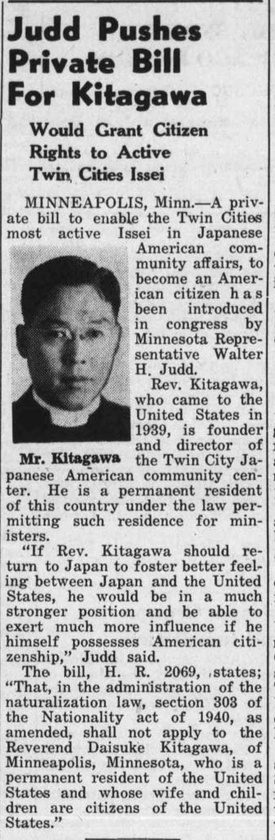

Kitagawa’s activities earned him numerous admirers, including members of Congress. On February 10, 1951, the Pacific Citizen reported that Senator Walter Judd of Minnesota (whose leadership in legislation to allow Japanese immigrants to naturalize ultimately led to passage of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952) introduced a private bill that would enable Kitagawa to become a U.S. citizen, despite the ongoing restrictions against naturalization of Japanese nationals. Reverend Kitagawa also appeared briefly before the President’s Commission On Immigration and Naturalization in October 1952 to communicate a statement on behalf of the Twin Cities JACL in support of the McCarran-Walter Act.

In January 1952, Reverend Kitagawa enrolled in the University of Chicago’s Divinity School as a doctoral student. Although Kitagawa took leave in August 1952 to return to his work in Minneapolis, Kitagawa returned to Chicago in 1954, and eventually completed his doctorate that same year.

In February 1953, Minneapolis voters elected Kitagawa to be chairman of the Mayor’s council on race relations. In keeping with his position, Kitagawa began turning his attention towards other groups. In July 1953, Kitagawa published a report on the status of Native Americans in Minnesota and the potential role of Christian organizations.

Based on meetings with local Native American and Christian leaders, Kitagawa’s report argued that in order to deal with the impact of centuries of animosity generated by the displacement and dehumanization of Native Americans, relations between whites and Native Americans needed restructuring, and he called for the need to develop better intergroup relations between Native Americans and other racial groups in the Twin cities. Kitagawa’s report was issued at the same times that the Bureau of Indian Affairs announced its policy to terminate Native reservations.

The termination policy, ironically enough, was developed by BIA Director Dillon Myer, the former head of the War Relocation Authority, who himself cited Japanese American resettlement as a precedent for relocating Native Americans to the cities.

While Kitagawa did not explicitly endorse the BIA’s termination policy, he advocated the movement of Native Americans away from reservations, arguing that the “entrapment” of Native Americans on reservations contained them from participating from wider society. Kitagawa cited his own experiences at Tule Lake concentration camp as an example of the harms of confinement upon the individual’s spirit.

One line in Kitagawa’s report on Native Americans that stands out is his views on Christian hypocrisy: “some of the most serious mistakes had been made by the most sincere Christian people as they sincerely tried to live up to their Christian beliefs and convictions.” This viewpoint speaks to his ongoing frustration with the apathy of most Christians towards civil rights.

In fall 1954, Kitagawa and his family left Minneapolis to work for the Protestant Episcopal Church in New York City. He and his family settled in Leonia, New Jersey. In August 1955, Kitagawa and his family travelled to Japan, where he surveyed education. In October 1955, Reverend Kitagawa travelled to Switzerland to study at the World Council of Churches’ graduate school. He then joined the World Council of Churches as a staff member, where he headed their study on global social change and global race relations. As part of his job, Kitagawa made regular trips to Geneva, Switzerland, and parts of Africa.

Kitagawa wrote frequently about his missionary work and the racism reinforced by white missionaries. In 1959, Kitagawa authored an article for Political Quarterly that applied his work on minority relations in the U.S. to world affairs. Titled “The West and the Afro-Asian World,” Kitagawa asserted that in order for states in Africa and Asia to become successful, the relations between Western colonizing powers and Africa and Asia need to be transformed from their existing majority-minority relationship. He published a similar article, titled “Church and Race in Africa,” on the ethics of missionary work in Africa for The Christian Century on May 17, 1961.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, Reverend Kitagawa immersed himself in the struggle of the Civil Rights movement. On April 24, 1963, Kitagawa spoke before the United States Conference for the World Council of Churches. In his speech, made before 200 church leaders, Kitagawa stated that black Americans had cast a vote of “non-confidence” towards white Christian leadership, and argued that neutral, well-meaning white Christians were just as harmful as outspoken racists in perpetuating racism. The speech caught the attention of multiple publications, including the New York Times, as well as several papers throughout the Deep South.

On July 4th, 1963, Kitagawa joined several hundred other protestors in picketing at Gwynn Oak Park, an amusement park on the outskirts of Baltimore, in protest of its segregation policy. Kitagawa, Episcopal Bishop Daniel Corrigan, and 283 other protestors were arrested by Maryland police and charged with trespassing. Among those arrested included famed civil rights activist Michael Schwerner, who, along with James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, was later murdered in Mississippi by the Ku Klux Klan for helping African Americans register to vote. The protest was a key event in the Civil Rights Movement, and was later dramatized by Baltimore native John Waters in his 1988 comedy Hairspray.

Kitagawa continued to call for more action from the Episcopal Church. On July 22, 1963, the Globe and Mail of Toronto quoted Kitagawa stating that the Episcopal church is on “the verge of losing its soul” by maintaining itself as a lily-white institution.

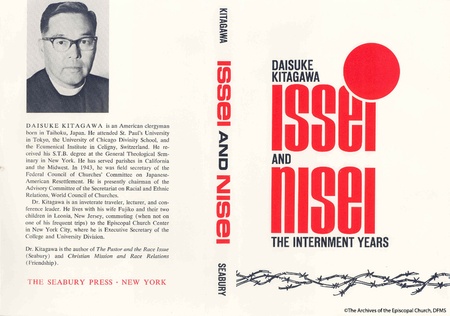

At the height of his career, Kitagawa authored two books. The first, titled The Pastor and the Race Issue, was published in 1965 by Seabury Press. Echoing his previous work for the World Council of Churches, he called for a less paternalistic view of missionary work. Kitagawa made clear in his first book that racism was an issue plaguing both the U.S. and the world, and he offered guidance towards more self-conscious missionary work for ministers dealing with different groups.

His second book, and perhaps his most famous, would become one of the first memoirs of the incarceration. Titled Issei and Nisei: The Internment Years, it was published by The Seabury Press in 1967. In it, Kitagawa provided a study of the challenges that faced both the Issei and Nisei during the incarceration, based on his own observations.

As with later memoirs that documented life in camp, such as Monica Sone’s Nisei Daughter, Issei and Nisei followed the existing pattern of praising the strength of the community and the downplaying the negative aspects of camp. Nonetheless, Kitagawa presented one of the first glimpses into the harsh conditions at the Tule Lake Segregation Center, and exposed the tensions facing those confined there over questions of loyalty. Kitagawa dramatized the disillusionment felt by the “no-no’s” and their internal conflict over their American identity.

Issei and Nisei was also one of the first memoirs of a religious leader in camp, and highlighted the importance of faith for Japanese Americans during the incarceration. Following his death in 1970, a new edition of Issei and Nisei was published, with a brief foreword by Senator Daniel Inouye.

Reviews of Issei and Nisei were few; no reviews appeared in the Pacific Citizen or in the Rafu Shimpo. One review in The Kansas City Star by a local resident, Paul Williams, praised the book as a testament to the strength of Japanese Americans such as his neighbors who resettled in Kansas City. Historian John Modell, who later edited and published social worker Charles Kikuchi’s diary in 1973, wrote a critical review of Issei and Nisei for the Pacific Historical Review. While Modell thought that Kitagawa’s insights into camp life were interesting, he argued Kitagawa failed to deliver a “collective autobiography of the Japanese American community as a whole.”

On Friday, March 27, 1970, Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa died unexpectedly in Geneva, Switzerland at the age of 59. His sudden death shocked many, and his body was brought back to New Jersey to be interred in Hackensack, New Jersey. He was survived by his wife, Fujiko, and son John, who also became an Episcopal priest. His death was reported by the New York Times and the Rafu Shimpo.

Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa’s life work demonstrates the deep impact that the incarceration had on his views of race relations and religion. While not all clerics of Japanese ancestry readily associated their own experience with the global struggle against racism, Reverend Kitagawa applied the lessons of the incarceration, and the disillusionment it wrought upon those confined, in his civil rights advocacy for African Americans and Native Americans.

Likewise, Kitagawa’s writings, such as Issei and Nisei, provided a written record of events at Tule Lake that remains cited by scholars. While a number of books, such as Dorothy S. Thomas and Richard Nishimoto’s The Spoilage, Michi Weglyn’s Years of Infamy and Edward Miyakawa’s Tule Lake, also shed light on life within Tule Lake, Kitagawa’s Issei and Nisei provides a unique first-hand account of the chaos that defined the Tule Lake experience and the bitter resentment felt by Issei and Nisei alike towards their unjust confinement.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen