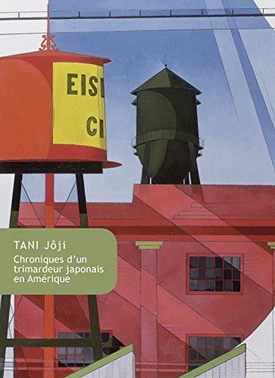

Having reflected on the life and work of Hasegawa Kaitarō, I now wish to discuss the new French edition, translated by Gérald Peloux, of the Tani Jôji Chronicles. The volume starts with a prologue, a kind of poem whose verses evoke, in impressionistic images, the different places the author visited overseas, such as Shanghai; Australia; Chicago; Elizabethtown, Kentucky; Dalian and Sujiatun, Manchuria; Montreal; Valparaiso, Chile; and finally New York. For example, among the author’s impressions of the port of Cardiff, Wales were “Various tobacconists/ the bowler hats of the Jews/ Necessary for sewing—very useful for you sailors/ a shilling six pence each.” It then unfolds as a series of tales of life in jazz-age America, recounted in the voice of George Tani, a young Japanese who comes to the United States to attend college, then spends five years as a wanderer (he calls himself a “hobo”), going across the country and around the world.

In a first section, “Notes of a Vagabond,” the narrator explains that during this period, he held a dizzying variety of jobs in different locations, mostly short-term, including a dentist’s assistant in Oberlin, Ohio; porter in a “blind pig” in Cleveland’s Central District; scorekeeper at a summer resort in Jackson, Michigan; auto worker in Detroit; candy vendor at a movie theater in Indiana; barker and “puller-in” in Cedar Point, Ohio; coal stoker on a ship traversing the oceans; and so on. For a time he even ran his own diner in Detroit, the Eagle Lunch. His intention is to recount some of the interesting stories that he picked up during his wild days in America.The section is followed by a diverse series of tales of the narrator's adventures. They are populated by a colorful cast of characters, including gamblers, boxers (Jack Dempsey makes an appearance), farmers, Panamanian women selling bananas, African American laborers, plus sightings of Charlie Chaplin and (perhaps) Rudolph Valentino.

The book is a fascinating example of Japanese modernist writing. In addition to the picaresque stories it tells, it features the author’s experimental language and writing style. The translator explains in a prefatory note that the original text represents a kind of visual and semantic game between Japanese and English, with different forms of writing mixed together—Japanese kanji, hiragana, and katakana, plus foreign words transliterated with furigana (indicators of pronunciation). The author makes liberal use of English words and phrases, including slang and dialect, that are placed directly in the text. Sometimes the words or phrases are rendered slightly incorrectly—whether this was a deliberate stylistic move or a mistake by the author or the publisher is unclear. (A nice example of Tani Jōji’s style can be seen in Kyoko Omori’s translation of his story The Shanghaied Man (1927)—to my knowledge the only Tani Jôji work to appear in English—which is published in the Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature.)

The Tani Jôji book is also a foundational transnational Asian American text. While Hasegawa was not the first Japanese writer to produce tales of the author’s life in America—Nagai Kafu’s Amerika Monogatari, in particular, preceded his work by two decades—the figure of Tani’s fictitious Meriken-Jappu (‘Merican-Jap’), offers a wonderously subversive and satirical portrait of the immigrant generation from Japan and their experience in the United States.

In a sense, the Tani Jôji stories serve as a counterpoint to Shōson Nagahara’s novel Lament in the Night, (which was originally published in 1925, the same year that Tani began publishing his stories). What Steven Yao says of Tani is also true of Nagahara, that the characters they devise are “transpacific migrant Japanese protagonists living as hobos in America who confront… various challenges deriving from the discriminatory economic and racial order of the United States.” Indeed, the main characters in both authors’ works are limited in their prospects in America, bereft of funds, and sometimes forced to work as itinerant laborers or scramble for food and lodging.

A big difference between them is that while Nagahara dramatizes the life of downtrodden Japanese immigrants in the Japantowns of the West Coast, Tani Jôji sets his work outside the ghetto, and his protagonist deals with a larger society. Indeed, in some ways Tani’s Chronicles anticipate Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, which deals with the same time period but which appeared a decade later. Both are fictions informed by autobiography, which treat in ironic fashion the experience of Asian migrants in cosmopolitan America. Both Tani’s and Kang’s protagonists come to the United States seeking an education, then run though experiences as domestic laborers, farm workers, and salesmen, in hot pursuit of their own version of the American dream. Both works feature a diverse cast of characters, including African Americans, and both authors offer sharp social commentary, with critiques of white American racism, paternalism. and materialism.

Further, while Nagahara paints somber naturalistic portraits of down-and-out people, Tani’s sketches are more light-hearted. While his Nikkei characters are colorful, they are not losers or victims. Rather, they are self-confident men able to navigate American society with verve (In one story, Tani affirms that Westerners, from a general point of view, are at a level of civilization far below that of Japanese). One might even go so far as to say that his characters include numerous “tricksters” who are adept at besting Westerners through guile. (Scholar Nagayo Homma has summarized the plot of one of Tani Jôji’s short stories not concluded in the collection, Tani Jôji, Merkien-Jappu shobai orai [American Jap’s business dealings]. This tale concerns a Japanese American from the West Coast who is so cunning and skillful that when he meets a white American from Louisiana, he manages to take from him not only $10,000, but the man’s wife as well.)

Several of the Tani Jôji stories end with unexpected twists which reveal how the Japanese characters surmount racism. In one story, Jimmy Chiba, a Japanese jujitsu master who works as a bouncer in a speakeasy in Chicago, subdues a troublesome drunk twice his size, then literally throws him out of the bar. In another, a Japanese man seated on a streetcar in Cleveland, harassed by a white racist, finally rises to the challenge and flattens his tormenter with a single punch, and is revealed to be the middleweight boxing champion Young Togo. “I barely touched him,” he states nonchalantly.

A third story concerns Mike, a Japanese pool shark and sporting man who takes the narrator to see a baseball game, and sits with him in the box seats. After being greeted in friendly style by a man in a baseball uniform, with whom he shakes hands and discusses sports, Mike introduces the narrator to his American friend—Ty Cobb. One of the most comic stories centers on Sam Kagoshima, a former circus strongman whom the narrator employs as a cook in the diner he operates in Indiana. One evening, three white men enter the diner and ask for Chinese food. The narrator explains, with increasing exasperation, that they do not serve Chinese food, and that he is Japanese. When the men suggest that Chinese and Japanese are the same, he retorts that by the same logic, as white Americans they are the same as Jews and Blacks. The men are furious at this remark and threaten the narrator, whereupon he calls Sam Kagoshima in from the kitchen. Sam’s muscular physique strikes fear into the bullies, and his acrobatic moves fill them with awe.

One especially notable aspect of Tani Jôji’s collection is a long story The Double Cross, which features Edward Morry, a Nisei born in California (originally named Mori). “Eddie” accompanies the narrator on his wanderings and leads him into various kinds of trouble. When Edward goes into business, he is transformed. The narrator is stunned to see him sporting a bowl haircut and snappy Western clothes, but is forced to admit that such get up, which he had deplored seeing on people in Japan, nonetheless fits his American friend like a glove. The story, which appeared in a period during which the Nisei generation often received a bad press in Japan, offers a unique portrait of a multidimensional American-born Japanese character.

© 2022 Greg Robinson