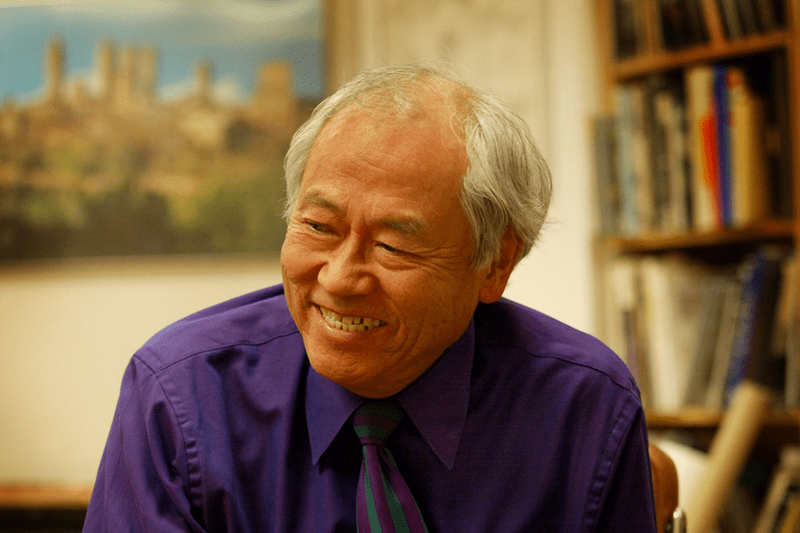

ST. LOUIS — Gyo Obata, FAIA, a world-renowned architect who cofounded HOK in 1955 with a vision for enhancing lives through building design, passed away on March 8, 2022. He was 99.

Obata was one of three principals who built HOK from a regional, St. Louis-based architectural practice into one of the world’s most respected global design, architecture, engineering and planning firms. His distinguished career spanned six decades. From the time of his retirement in 2012 and continuing into 2018, he maintained an office in HOK’s St. Louis studio, where he regularly served as a design advisor to his colleagues.

“Gyo’s extraordinary career at HOK continued into his 90s, and he served as a mentor to several generations of designers including myself,” said HOK Chairman and CEO Bill Hellmuth, FAIA. “As an example to all of us, he led HOK to become the largest architecture-engineering firm in the United States while never abdicating his role as a designer of significant projects.”

Underpinning Obata’s pioneering design approach was a fundamental belief that each project must be approached without preconceptions and designed to serve the needs, values and aspirations of the people and community it serves. Rather than imposing his will upon a project, he paid close attention to the needs expressed by clients and then let the project guide the design of a building that would bring meaning and enjoyment to its visitors and inhabitants.

“Gyo embodied everything that’s honorable about the architectural profession,” said Bill Valentine, FAIA, HOK’s chairman emeritus. “Instead of designing for the fashions of the times or to make a personal statement, Gyo designed to improve lives. He was a kind, thoughtful man who developed warm, personal relationships with his colleagues and clients. People believed in him, which is an essential part of turning drawings into buildings.”

A strong proponent of sustainable design, Obata’s work is characterized by an efficient use of materials and sense of harmony with its natural environment. “If you see architecture as a conversation with the surrounding environment, then Gyo is the ideal conversationalist,” wrote George McCue in a 1983 cover story for St. Louis Magazine. “The greatest virtue his buildings possess is the great ‘courtesy’ they display toward their environment.”

Obata was an advocate for a holistic approach to design in which architecture, engineering, interior design, planning and landscape architecture are fully integrated and delivered by a single multidisciplinary design team. This approach helped drive HOK’s ongoing expansion into new specialty practices, market sectors and geographic regions.

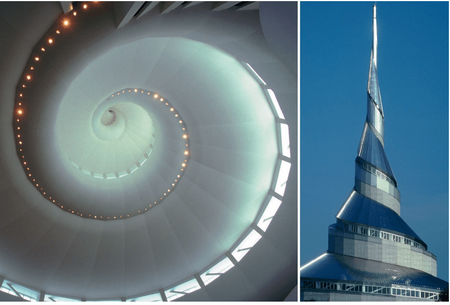

During his 50-year tenure as HOK’s design principal, Obata shaped iconic, award-winning projects around the world. A few noteworthy examples include the Priory Chapel at Saint Louis Abbey, Creve Coeur, Mo. (1962); The Galleria in Houston (1970); Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (1973); Bristol-Myers Squibb Campus, Princeton, N.J. (1973); National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. (1976); King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (1983); King Saud University in Riyadh (1984); Community of Christ Temple, Independence, Mo. (1994); and the Japanese American National Museum Pavilion in Los Angeles (1998).

With an approach to life that regarded each day as a portal to possibility, Obata also loved spending time with his family and friends, gardening, tennis, art, travel, reading, his dogs, birds, music, theater, opera, films and cooking.

A Life of Design

Obata was born in San Francisco on Feb. 28, 1923. His parents, both artists from Japan, met in San Francisco after emigrating to the U.S. His father, Chiura Obata, introduced the classical sumi-e style of painting to the West Coast, and his mother, Haruko Obata, did the same for ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging.

“Our house was like a studio, and was always filled with paintings and flowers,” said Obata in a 2010 book by Marlene Ann Birkman, “Gyo Obata: Architect | Clients | Reflections.” “My parents were both great teachers and taught me life’s most basic lesson: to listen very carefully.”

Obata was 18 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and an anti-Japanese hysteria swept the U.S. He enrolled in the architectural program at UC Berkeley in 1942, but his education was interrupted during his freshman year by the internment of approximately 117,000 people of Japanese ancestry in the U.S.

The night before his parents, brother and sister were relocated to an internment camp in Northern California, Obata boarded a train to St. Louis to continue his architectural training at Washington University, which at the time was one of the only U.S. universities that would accept Japanese American students. His father had secured special permission from the local provost marshal for him to leave the region.

He earned a Bachelor of Science in architecture from Washington University in 1945 before continuing his architectural education at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. There he studied under master Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, the father of Eero Saarinen, architect of the iconic Gateway Arch in St. Louis. In 1946, Obata received a Master of Architecture and Urban Design.

“Saarinen’s teachings had an enormous positive influence on me,” said Obata in a 2006 interview. “He emphasized the relationship of every element in a design and the importance of integrating them, from the smallest through the largest. Since then, I have always been interested in working on large-scale projects where many smaller parts must fit within the greater whole.”

After serving with the U.S. Army in the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska, Obata joined the Chicago office of architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1947 as a designer.

In 1951, the St. Louis architecture firm Hellmuth, Yamasaki & Leinweber (HYL) recruited him as a design assistant to Minoru Yamasaki, an architect who would later design the World Trade Center in New York City. Obata’s collaborations with Yamasaki included the design of the signature passenger terminal at St. Louis Lambert International Airport that opened in 1956. Credited for helping change the visual vocabulary of airports and being the forerunner of modern airport terminals, the building features aerodynamic lines and a series of low-slung arches that celebrate the concept of flight.

When HYL reorganized in 1955 as Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK), Obata, at the age of 32, was appointed principal of design. Together with George Hellmuth (1907-1999), who led marketing and business development, and George Kassabaum (1921-1982), who oversaw production, the partners pioneered a tripartite business model that would come to define the modern multidisciplinary architecture practice.

Making His Mark on St. Louis

Much of Obata’s earliest design work for HOK consisted of school buildings for a growing post-World War II population. Projects such as Bristol Primary School in suburban St. Louis not only addressed the post-war need for classrooms, but also introduced innovative ways to create shared and collaborative teaching spaces — a theme that would continue to define his buildings.

In 1961, Obata helped HOK win its first major university commission: the planning and design of a new campus for Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville (SIUE). His innovative campus master plan, which veered away from the large, monumental and institutional style of architecture that at the time was prevalent in new campuses, shaped what then SIU President Delyte W. Morris called a “bold and experimental institution.”

He first achieved international acclaim for his innovative design of the Priory Chapel at Saint Louis Abbey, which features an iconic circular facade with three tiers of whitewashed, thin-shell, concrete parabolic arches.

“It is an outstanding demonstration of the ingenuity of man in honoring almighty God,” said Joseph Cardinal Ritter, archbishop of St. Louis, when the building opened. A 1962 issue of Time magazine called it “The newest and perhaps most striking round church in the U.S.,” and Architectural Digest named the structure “one of America’s greatest hidden treasures.”

Other signature St. Louis projects that Obata designed include the James S. McDonnell Planetarium at the St. Louis Science Center (1963); Nestlé Purina PetCare Company headquarters (1969); America’s Center Convention Complex (1977); One Metropolitan Square (1988); The Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo (1989); Saint Louis Galleria (1991); Missouri History Museum Emerson Center (1999); Boeing Leadership Center (1999); Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse (2000); Washington University School of Medicine Farrell Learning and Teaching Center (2005); and Centene Plaza (2010).

Based on his significant contributions to the St. Louis region, Obata was inducted to the St. Louis Walk of Fame in 1992.

Expanding His Impact

Obata’s innovative design solutions have shaped an ongoing series of important cultural and civic buildings that fulfill their functional requirements while creating memorable public spaces.

His design of The Galleria in Houston, which opened in 1970, reimagined the shopping center environment through the introduction of a multi-level indoor mall with an ice-skating rink at the center.

In 1973, his design of the original Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport established America’s first regional airport, heralded both for its convenience and its crisp, clean detailing.

Located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the National Air and Space Museum exemplified Obata’s emphasis on structure, space and light. The building’s simple, monumental limestone volumes were linked by atria, providing an effective venue for moving large groups of people efficiently through a multitude of displays. Dedicated during America’s bicentennial celebration on July 4, 1976, it is one of the world’s most-visited museums.

Obata’s design of the Levi’s Plaza campus, which is nestled into a San Francisco urban hillside, enclosed a public park and fountain without intruding on the cityscape. San Francisco Chronicle architecture critic Allan Temko called Levi’s Plaza “a gift to the city” and in 1982 Time magazine named it “Building of the Year.” Today, the campus retains its architectural integrity and fits comfortably within its historic urban setting along San Francisco’s Embarcadero.

Obata also contributed to HOK’s expansion into Europe, the Middle East and Asia Pacific.

His design of two iconic projects in Saudi Arabia established HOK’s reputation as a firm uniquely qualified to design large, complex projects anywhere in the world.

In 1983, King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, crystallized the concept that an international airport could serve as a gateway to a city, country and entire culture. Several of the airport’s organizing themes, including the use of triangular relationships, are derived from religious and secular Islamic structures.

King Saud University, which opened in 1984, captures the sensibility of a desert citadel, with extraordinary spaces to be discovered within its protective, enclosing walls. Ideas around ease of movement, separation of disciplines, the effects of climate and the creation of diffused lighting inspired the design.

A Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, Obata received the Gold Honor Award from the St. Louis chapter of the AIA in 2002. Other awards and honors include the Lifetime Achievement Award in the Arts from the Japanese American National Museum (2004); the Lifetime Achievement Award from the St. Louis Arts & Education Council (2008); the Dean’s Medal for the Sam Fox Awards for Distinction from Washington University (2008); and the Thomas Jefferson Society Award from the Missouri Historical Society (2016). He is featured in several books.

Visit HOK’s YouTube channel for more on the life and work of Obata, including thoughts and stories from the man himself.

* This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on March 12, 2022 and the main information were derived from the HOK website.

© 2022 Rafu Reports