On November 6, 1943, the California State Assembly’s Committee on the Japanese Problem convened in the small town of Santa Maria, California. Known throughout the state as an agricultural hub, Santa Maria and its twin town of Guadalupe had shared one of the state’s largest Japanese American agricultural communities until April 1942, when the government forced its members into camps under Executive Order 9066. At the November 1943 meeting, the committee, led by Assemblyman Chester Gannon, met with a group of local leaders to discuss the potential return of the Japanese American community after the war. Overwhelmingly, the leaders signaled their refusal to let Japanese Americans return to the community.

Of the group, one member stood up in favor of welcoming Japanese Americans back into the community. Reverend Aaron Allen Heist, a minister and ACLU leader, not only called for the return of Japanese Americans, but also denounced the heavy-handed tactics of Santa Maria’s leaders in pressuring people to sign petitions banning Japanese Americans. Reverend Heist’s actions during that period not only demonstrate his courage, but attests to his long career as champion of civil rights for the oppressed.

Aaron Allen Heist was born on January 10, 1885 near Middleville, Michigan, to a German father and Canadian mother. After graduating from Northwestern University in 1908, he moved to Warrington, Oregon to work as a Methodist preacher. During this time, he helped lead a prohibition campaign in Oregon, thereby gaining his first experience of the activism that defined his later career. In 1912, Heist entered Garret Biblical Institute in Evanston, Illinois, from which he graduated in 1916. On June 20, 1917, Heist married Elsie Philip, a schoolteacher, in Columbia, Oregon. The couple soon had two children.

In 1921, the Heist family moved to Aberdeen, Washington. While in Aberdeen, Heist threw himself into labor advocacy. He contributed to the leftist newspapers Astoria Labor Press and the Southwestern Washington Labor Press. As part of his articles on Christianity and labor rights, Heist supported the rights of local lumber workers in organizing a local chapter of the International Workers of the World. In 1923, Heist led a repeal campaign against Washington’s criminal syndicalism law, which prevented workers from organizing unions.

In February 1923, in tribute to his abilities as an organizer, Heist was appointed Associate Secretary of the Methodist Episcopal Social Service Foundation. Over the following years, Heist used his new platform to be a labor advocate. In a meeting of church leaders, Reverend Heist criticized the greed of American businessmen, stating that many business leaders who claimed to be Christian actually betrayed their beliefs.

In a similar vein, Heist preached that warmongering violated Christian values. He denounced his alma mater, Northwestern University, for giving pro-military speakers a platform, and supported the passage of an anti-war resolution at a conference of the Methodist Episcopal church.

In 1926, Reverend Heist and his family relocated to Denver, Colorado, where Heist led the Grace Community Church. Heist transformed the Grace into a site for labor organizing. In June 1926, Heist helped to organize a rally in defense of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian American anarchists wrongly accused of murder and later unjustly executed. The rally attracted thousands of participants. During the 1927 – 1928 Colorado Miners’ Strike, Reverend Heist spoke out in defense of the miners and hosted regular meetings of supporters at his Denver church.

In 1930, the Denver labor newspaper Organized Labor declared Heist to be “a preacher who really believes in the union label as a symbol of justice…He is truly a worthy apostle for the work he is engaged in.”

In addition to being a spiritual and labor leader, Heist campaigned for better race relations. As head of Denver’s Inter-Racial Commission, Heist corresponded with NAACP leader W.E.B. Du Bois, and invited Du Bois to speak in February 1927 on interracial political solidarity. Like Du Bois, Heist viewed racism as one of the defining issues of U.S. politics, though he attributed such divides to class politics.

In 1933, amid the Great Depression, Reverend Heist moved to Los Angeles, and in the period that followed, he served as an itinerant minister in various neighborhoods of the city. As with his previous missions, Heist zealously championed labor issues during his time in Los Angeles. The Congress of Industrial Organizations hired Heist to help with education and public relations, and appointed Heist as secretary of their Inter-Religious conference.

In July 1941, Heist received an assignment to run the First Methodist Church of Santa Maria, and left Los Angeles for his new job. The move brought Heist into frequent contact with Japanese Americans. During his early months at the First Methodist Church, Heist held several meetings with Japanese American congregations of the Union Church of Santa Maria.

The surrounding climate was increasingly menacing following the outbreak of the Pacific war, as the majority of white residents in the Santa Maria valley supported forced removal of their Japanese American neighbors. On December 8, 1941, the Santa Maria Times printed large headlines about the bombing of Pearl Harbor and Japanese victories in the Pacific. The Times published the loyalty statement of the Santa Maria branch of Japanese American Citizens League, sent to the editor, but deceptively printed it under the banner headline “Many Japanese Arrested Here.”

On March 30, 1942, the Times approvingly announced the imminent departure of hundreds of Japanese American families. Local whites scooped up property and belongings of Japanese American families at “fire sale” prices. The remaining Japanese Americans departed Santa Maria on April 30th, leaving from the Japanese Union Methodist Church under armed guard.

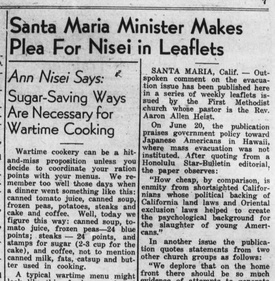

Noting the injustice unfolding before him, Reverend Heist began to speak out. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Reverend Heist and several other clergymen signed a joint letter asking the Department of Justice to protect the rights of enemy aliens and avoid “using the very totalitarian methods which we have decried.” The letter, printed in the February 5, 1942 issue of the Santa Maria Times and later in the Rafu Shimpo, denounced any suggestions of herding any enemy aliens or their descendants into concentration camps.

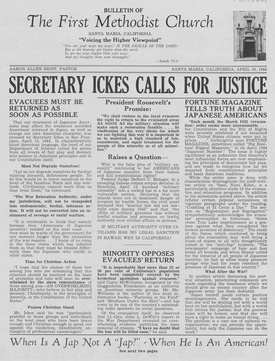

Soon after, Heist started a weekly bulletin, The Church Call, in which he penned articles denouncing the racial attitudes of Santa Maria’s leaders. In the June 21, 1943 issue of The Church Call, Heist decried the forced removal of Japanese Americans as “military necessity cloaking the jealousy and economic greed of California,” and lambasted the Santa Maria Chamber of Commerce for sending a racist letter to Congress calling for the permanent exclusion of Japanese American. Heist compared the Chamber’s action to the depredations of Nazi Brown Shirts.

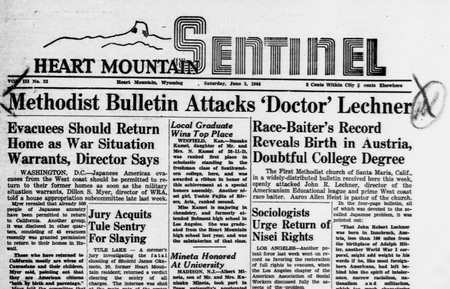

The Santa Maria Times reprinted the article alongside the angered response of local Santa Maria citizens. On June 24, the Santa Maria Times published an editorial that accused Heist of naiveté and declared its bias with stupefying transparency: “is it too much to ask that these few loyal Japanese suffer for the sins of the majority, especially when such segregation may be the saving of many loyal American lives? We think not.”

Following the issuance of its editorial, the Santa Maria Times maintained a steady campaign against Heist. In September 1943, it ran an article reporting that Heist had provided the opening convocation for a teaching workshop that featured Carey McWilliams. The Times described McWilliams as “controversial” and reminded its readers that he had been one of the first people relieved of duty as a state employee following the election of Governor Earl Warren at the start of that year.

On November 6, 1943, The Santa Maria Times reported Heist’s aforementioned statements to Assemblyman Gannon’s committee as well as his denunciation of the Santa Maria Chamber of Commerce. The editors strategically printed Heist’s response next to reports of the Tule Lake “riot” and exaggerated claims of violence within the camp. Two weeks later, on November 18, the Times again printed letters in response to Heist’s remarks, with one writer stating that Heist himself should be sent to Tule Lake.

In October 11, 1944, the Santa Maria Times printed an article stating that Hugh Bruce, the superintendent of Orcutt schools, who had publicly appealed for funds to support Heist’s The Church Call, might face backlash at a meeting of the school board. In fact, the day after the meeting, Bruce printed a letter stating he never made such any such appeal and distancing himself from Heist. On December 18, 1944, the Santa Maria Times announced the end of the West Coast ban on Japanese Americans. The news was accompanied by an article titled “Violence feared of Japs’ Return” that reminded readers of Heist’s previous statements before the Gannon committee.

Japanese Americans in the camps, for their part, paid close attention to Reverend Heist’s courageous acts. Inmates at the Gila River camp, where most of Santa Maria’s Japanese American community was confined, were the first to speak publicly in his defense. On August 12, 1943, the Gila News Courier praised Heist, stating he was risking the loss of his congregation in order to publish his bulletins and preach to his pastorate a “saner attitude of mind.”

At Heart Mountain camp, the Heart Mountain Sentinel republished an article penned by Heist for The Open Forum, an organ of the Southern California ACLU, that denounced the executive order and the fear-mongering practices of California politicians. The Sentinel also republished one of Heist’s articles from The Church Call that revealed that Dr. John Lechner, a noted anti-Japanese polemicist, was not in fact a licensed doctor.

On June 10, 1944, the Manzanar Free Press noted that CBS news commentator H.V. Kaltenborn had praised Heist’s journalistic work, stating the Church Call was “the first California publication I have seen which dares tell the truth about Americans of Japanese Ancestry.”

On July 8, 1944, the Minidoka Irrigator noted that Reverend Heist had submitted a resolution before a conference of Methodist leaders calling for the restoration to Japanese Americans of the right to return to the West Coast, and that the resolution was approved unanimously by the conference.

Outside the camps, Nisei also commented on Heist’s articles and his statements to the Gannon Committee. On July 17, 1943, The Pacific Citizen highlighted several statements from The Church Call advocating fair treatment towards Japanese Americans and asserting that the incarceration spoke more to the fears of West Coast whites than any questions of loyalty. On November 6, 1943, the PC quoted a report by Heist lauding Japanese Americans for their low crime rate, and “are keeping up their record in our American concentration camps.”

Reverend Heist’s bravery as a dissenter earned him wide recognition. In October 1945, the Southern California ACLU elected Heist as its director. Heist and his family left Santa Maria for Los Angeles in November, and permanently remained thereafter in the Los Angeles area. As before, Heist continued to speak out in support of Japanese Americans.

On October 15, 1945, the Pacific Citizen mentioned Reverend Heist’s opposition campaign to Proposition 15, which would extend California’s Alien Land Law. Heist characterized Proposition 15 as “a racist measure.” In June 1949, Reverend Heist penned an article for The Open Forum about the Evacuation Claims Act of 1948. The article, which later appeared in the Pacific Citizen, noted the fears facing Japanese Americans filing claims, and encouraged readers to file claims with the government. In September 1954, the JACL awarded a certificate of appreciation to Reverend Heist for his defense of Japanese Americans during the war years.

In the postwar years, Heist championed other social causes. In June 1946, Reverend Heist went to Terminal Island to protest the treatment of deportees at the immigrant detention facility there. In 1948, Heist joined African American civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph in protesting the continued segregation of the US military. In 1952, Heist founded the Citizens Committee to Protect American Freedoms, an organization which opposed the activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee as violating constitutional liberties.

Even after leaving Santa Maria, Heist’s activities continued to draw the ire of many Santa Marians. The Santa Maria Times, which labelled him as an “ultra-liberal,” mentioned his work with the ACLU and described his campaign against HUAC as “fishy.” On several occasions, the House Un-American Activities Committee inquired about Heist’s association with the Communist party, but Heist persevered. Reverend Aaron Allen Heist died on July 29, 1963.

Although many Americans came forward to support their Japanese American friends during the incarceration, few courageously stood up against the systemic racism that caused it. Reverend Heist’s advocacy in favor of Japanese Americans demonstrates Heist’s courage in the face of sheer opposition. It also attests to Heist’s commitment to spiritual justice and his quest to defend those victimized by racism and to end the unjust exploitation of workers.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen