The modern sculptor Leo Amino, who achieved fame in the postwar artworld but then faded from view, has been experiencing a rebirth of public interest in recent years. Amid the new attention that Amino’s work is receiving, it is interesting to retrace the path that took him to his initial renown.

He was born Ichiro Amino on June 26 1911. His birthplace was Taiwan (then part of Japan), where his father was on agricultural assignment for the Japanese government. Amino grew up in Tokyo. While both of his parents were artistic—his father practiced calligraphy and his mother was interested in ikebana—he did not receive any academic training in art.

In 1929, the young Amino travelled to the United States and enrolled in San Mateo Junior College. The following year, Nichi Bei Shinbun recorded that he was one of a group of Japanese students recently arrived in the United States who were being honored at a ceremony for new members at the Japanese YMCA in San Francisco.

After leaving San Mateo, Amino took up work in a Japanese bank in San Francisco. He eventually tired of his job, and in 1935 he moved to New York’s artistic mecca of Greenwich Village. He briefly attended New York University, then took a job with a Japanese wood importing firm. Using ebony samples he took home from work to carve, he threw himself into sculpture as a self-taught artist. Sometime during this period, he took the American name “Leo.”

In 1937 Amino enrolled at the American Artists School in New York, where he took classes in “direct carving” with renowned sculptor Chaim Gross. Direct carving is designed to produce simplified structural forms which emphasize natural properties of materials, such as wood grain. In 1938, Amino took a trip to England, where he met artist Henry Moore. He was also heavily inspired by the work of surrealist artists such as Joan Miro and Jean Arp.

Within an astoundingly short time, Amino had developed sufficiently as an artist to be invited to present at public exhibitions. His first break came in January 1939, when his work was included in an exhibition by the United American Sculptors collective at the New School for Social Research. Art Digest noted: “Leo Amino has carved lovingly a wood Mother and Child that exploits the grain sensitively.”

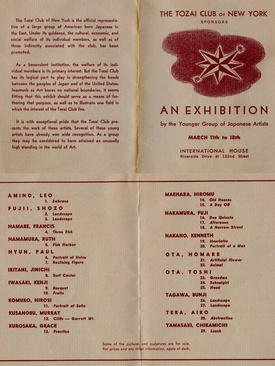

Another break came later that same year when he was invited to exhibit together with Isamu Noguchi at the New York World’s Fair. He likewise participated in a show at International House, near Columbia University. The exhibition, entitled The Younger Group of Japanese Artists, featured Amino’s work alongside that of other Issei and Nisei artists.

In January 1940, Amino—still just 28 years old—had a first one-man show of his sculpture at the Montross Gallery in midtown Manhattan, in which he presented 20 pieces carved in wood. Caryle Burrows, writing in the New York Herald Tribune, noted the seriousness of the sculptor and his technique. “If Mr. Amino himself appears a remote personality, his carvings, which present a synthesis of the subject matter generally devoid of all natural detail, are even more detached from reality.” Burrows nonetheless extolled the expressive nature of works such as “Embrace,” “Flight,” and “Lamentation.”

Critic Howard Devree, writing in The New York Times, praised the artist’s skilled use of wood grain in works such as “Ballet Dancer” and “Neanderthal Man,” as well as his “strong if rather not fully realized sense of rhythm.” Soon after, “Lamentation” was featured in a show of the United American Sculptors at the New School for Social Research, and a photo of the sculpture was featured in the New York Times. Meanwhile, “Struggle” was featured in an exhibition of the United American Artists at Rockefeller Center, and was described as “excellent” in a New York Times review by critic Edward Alden Jewell.

In December 1940, Amino held another show, at the Artists’ Gallery. “J.L.,” writing in Art News, described Amino as “a Japanese artist who subdues his material to a smooth satiny surface,” and lauded such works as “Billiard Player” and “Unyielding Spirit” for their amazing emotional power. This time, critic Howard Devree was more negative, complaining in the New York Times that the artist’s approach was “too modern” and distorted.” Devree’s aesthetic judgment may have been shaped by political factors: he denounced Amino as humorless for including a piece called “Lynching” (an assemblage sculpture of a motionless figure hanging from a tree) which Devree termed “hardly the sort of thing to contemplate in the home while imbibing the morning coffee.”

As if to compensate for Devree’s barbs, Ruth Green Harris published a piece in the Times two weeks later lauding Amino’s wood sculpture technique: “Leo Amino’s approach differs somewhat from that of Chaim Gross. He too would preserve the woodiness of wood, but is less interested in a quality of tree-i-ness. This may be partly because his compositions are small in size and are often designed with the small interior in mind.”

In September 1941, Amino exhibited at two venues which would prove longstanding homes for him. First, he contributed to a show at the Artists’ Gallery. Meanwhile, he mounted a one-man sculpture show at the Clay Club (now known as SculptureCenter).

Helen Boswell wrote a positive commentary on the latter show in Art News (which also reproduced Amino’s work “Torso in Concave No. 1”). Unlike Howard Devree, Boswell singled out “Lynching” for particular praise: “Correlative concave and convex surfaces come into play, the surfaces being divided by calligraphic ridges.” Carlyle Burrows again praised Amino, mentioning the “poetic symbolism” in works such as “Despair,” “Lamentation,” and “Renunciation.”

Howard Devree, for his part, was more positive about this show than its predecessor, writing in the New York Times that Amino “seems to be working into a more formally decorative, abstract vein, retaining his poetic feeling for curved masses and flowing line and making striking use of the grain of wood.”

Although Leo Amino maintained little visible connection to Japan or local Japanese communities in the 1930s, his life was influenced by the coming of World War II. As an enemy alien, he was subject to restrictions on his movements and bank accounts. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, he joined the group of New York Japanese artists led by Yasuo Kuniyoshi who signed an antifascist resolution condemning Japan’s attack and pledging full support as artists for the war effort, offering “to bear arms if necessary to insure the final victory for the Democratic forces of the World.”

According to one source, Amino was engaged during the war years as a translator by the US Navy. Certainly, his active prewar exhibition activity slowed to a halt over the months that followed, though in January 1942 his work “Women Washing” was presented in a show at the Plainfield Art Gallery in New Jersey.

In 1943 Amino mounted a new show at the Artists’ Gallery, this time of compositions in wood and plaster. The artist explained that these new works followed his concept of “integrating space as a positive element in composition.” Art Digest, which reproduced Amino’s Henry Moore-like “Pieta,” expressed ambivalence. The critic extolled the artist’s talent for wood sculpture, stating “he seems to know their grain and markings in an almost clairvoyant way,” but was dubious about the merits of the works in plaster.

Throughout that year, Amino participated in other shows. In March his work was part of a show at Puma Gallery. In October, he contributed to a show at the Clay Club. Later he took part in a Christmas show at the Artists’ Gallery.

After December 1943, Amino did not show his work for another 15 months. He nonetheless continued developing his art, both in technique and materials. In March 1945 he had a new show of works in magnesite, a carbonate mineral, at the Bonestell Gallery. Carlyle Burrows reported breathlessly on the progress that Amino had made with the magnesite, citing particularly the pieces “Temptress” and “Motherhood” for their “graceful contour, dignity of proportion and delicate color.”

Art Digest, which reproduced “Mother and Child,” expressed appreciation for the technical achievement of the medium and the artist’s “emphasis on flowing rhythms, strongly designed.” The show gained extra exposure when the New York Times ran a photo of Amino’s work “Calla Lily,” an abstracted flower with pistil that resembled a television satellite dish.

While Amino had generally resisted identification with Japan and held aloof from Japanese American communities, near the end of the war, he agreed to join the executive board of the Arts Council of Japanese Americans for Democracy, an antifascist group led by Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Amino also contributed to a group exhibition of Issei and Nisei artists sponsored by the War Relocation Authority and the JACL, among other groups. Perhaps symbolically, Amino’s contribution was a wood carving entitled “Embrace.”

The exhibition first opened in May 1945 at the New Jersey College for Women (now Douglass College) in New Brunswick, NJ. Following this initial showing, the exhibition moved to Chicago, Cleveland, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Rochester, New York—thereby providing Amino his first real national exposure. The stage was set for Amino’s rise to prominence during the postwar era.

© 2022 Greg Robinson