“Growing up Asian in America, we had the songs of our ancestors, but we no longer understood them. In our quest to be American, we’d often rejected the old music…. We were a songless people. We were missing something that we didn’t know we longed for — our own song.”

— Nobuko Miyamoto, Songwriter, dance and theatre artist, activist and Artistic Director of Great Leap

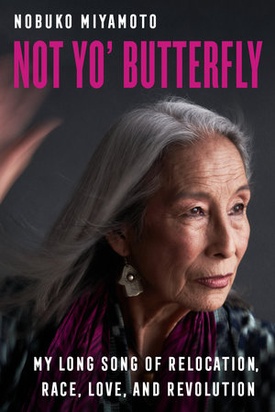

Recently, a writer friend sent me a notice about a new memoire: Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Song of Relocation, Race, Love and Revolution by American Sansei Nobuko Miyamoto. It was something about her confident mien and swag that made me order it and, thankfully, I did.

It is one of the most engaging reads that I’ve enjoyed for some time and an important reminder that none of the ongoing racial injustices that we’re suffering through now is new. If anything, understood in a broader historical context, this memoir presents an important, fresh perspective on what it means to be Asian in the US and Canada.

Miyamoto’s mom Mitsue’s father Tamejiro Oga, was from Tachiarai, Fukuoka, dad Mark was from Kumamoto. Both of her Nisei parents were born in Oakland. When grandfather Oga met Mark “a handsome half breed” whose father had married Lucy Harrison, a white Mormon lady, his response was “No! No good! Who is family?” This issue of interracial marriage would run through Nobuko’s life.

While centered mostly around LA, her activism took her around the US, growing out of the racial injustices that Japanese Americans experienced before, during, and after WWll. So, for Nobuko who “was learning about my own oppression, my people’s oppression, in the way I learn best: not through books but through my body, by being present.” Her remarkable Oz-like journey swept her up on a life journey that would have her labeled her as an ‘enemy alien’—a prisoner in Santa Anita Park racetrack in Arcadia, California (once the playground of celebrities like Errol Flynn, Spencer Tracy and Bing Crosby owned racehorses there), to a Montana sugar beet farm, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and ‘Fat Man’ plutonium bomb on Nagasaki, back to Utah and California, again: the proverbial land of milk and honey.

Her Issei grandfather Harry set the story into motion when he married Lucy Harrison at a time that challenged a lot of the social norms about race and marriage on both sides of the racial divide. Nobuko’s life work of challenging racial and religious stereotypes and fighting for social justice seems to have grown out of this kind of strength and moral fortitude. After her grandmother, Lucy, died when her father was 14, grandfather Harry moved the family from Parker, Utah, to California.

It was there where Dad Mark distinguished himself as an ambidextrous baseball pitcher at Hollywood High School. He played with the LA Nippons, a semi-pro team in the Japanese American League. After high school, with limited career opportunities, Mark joined the Issei and Nisei who were gardeners or in the produce business. He brought a truck and a second new Mack semi-truck in 1940, a time when some white farmers in California were calling for “Japs,” then farming nearly half a million acres, to be “removed”.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor offered the excuse many were looking for. In April 1942, those economic and race-driven pressures prevailed when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on that other day of infamy, February 19, 1942, declaring all “Japanese,” 120,000 in all, who lived within 50 miles of the west coast, into concentration camps. Members of Nobuko’s family were sent to Gila River, Arizona and Heart Mountain, Wyoming concentration camps. After a stint living in a horse stall at the Santa Anita race track, Nobuko’s family went to Glasgow, Montana to pick sugar beets.

After the end of the war, the family resettled in the Jefferson Park area of LA, a place where the usual restrictive housing covenants allowed Blacks, Japanese, and other people of colour to buy homes. Nobuko began dance lessons at the West Coast School of Music and Dance where she found her joy. Being called a “dirty Jap” was bad enough coming from a white boy but when her JA friend June’s sister said “We don’t want to play with someone like you!” pointing out that her father was half Japanese, a seed of moral outrage was planted that would grow and direct much of Nobuko’s lifework of activism.

The racial and religious cross sections throughout her life are fascinating to read about: dance led her to movie roles in The King And I (starring Yul Brenner) and Westside Story (starring Natalie Wood and Rita Moreno). Later, living and working as a dancer and singer placed Nobuko into situations where she had to come to terms with some of Hollywood’s worst exotic Asian stereotypes—that opened new doors to her better understanding of herself. And, it was when working on a documentary about the Black Panthers, Seize The Time, that opened new doors of her understanding to who she is and where she belonged. Her musical work in Yellow Pearl with Chris Iijima and Charlie Chin allowed her to explore other aspects of herself and to refine them.

Nobuko’s serendipitous life is a charmed one, indeed. Along the way, she experienced a series of epiphanies through contact with such giants in the Asian and Black Liberation movements as Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs, among many others.

Her story is as much about community building as it is about self discovery. I took away several lessons from this work: that the importance of seeing positive Asian role models in media cannot be underestimated (for Nobuko it was seeing Hawaiian “Hilo Hattie” on TV); being inspired by fellow Japanese American dancer role models “Yuriko” and Reiko Sato; working on the groundbreaking Flower Drum Song (1964) written by Yale-educated playwright CY Lee, and featuring a largely Asian cast that included Miyoshi Umeki, Jack Soo (Goro Suzuki), James Shigeta, and Reiko Sato.

Nobuko’s friends and mentors along the way, include Nisei dancer “Yuriko” (Martha Graham Dance Company) and husband Charlie Kikuchi; Nisei Reiko Sato (“one of the baddest samurai dancers I knew”); mother-in-law Mamie Kirkland born (1908-2019) in Ellisville, Mississippi (living through the 1917 East St. Louis race riots, a KKK cross burning in Ohio and march with Marcus Garvey); long-time supporter and friend Sansei Rev. Masao Kodani of Senshin Buddhist Temple in LA; and Chris Kando Iijima (1948-2005), poet, musician (Yellow Pearl), lawyer and legal scholar.

One of the most memorable events that she recounts was when she and Chris Iijima were contacted by John Lennon and Yoko Ono who invited them to perform on the Mike Douglas Show in 1972:

A producer asked them to ‘censor’ the lyrics of ‘We Are The Children,’ explaining, “Well — some of the words — you know — the housewives in the Midwest might think them subversive.”

Nobuko was righteously indignant: “YOU! YOU PUT US IN CONCENTRATION CAMPS AND NOW YOU’RE SAYING WE CAN’T SING THIS SONG!”

From ‘We Are The Children’ (credits: Charlie Chin, Chris Iijima, and Nobuko Miyamoto)

“We are the children of the migrant worker

We are the offspring of the concentration camp

Sons and daughters of the railroad worker

Who leave their stamp on AmericaFoster children of the Pepsi generation

Cowboys and Indians

Ride, red men, ride

Watching war movies with the next door neighbor

Secretly rooting for the other side…”

While working as a volunteer at a Free Breakfast for Children organized by the Black Panthers, Nobuko had the following epiphany: “Everyone was friendly. I didn’t feel odd or different…. It was the first time I felt recognized as a person of color, the first time I felt I fit in somewhere... I was witnessing Black men and women who were serving the people, not for money, not for glory or fame. In fact, it was dangerous work. They were taking responsibility for solving problems in their community. They had come to understand that the root of their problems was the capitalistic system, with a few at the top, exploiting the labor and resources of people of color and poor Whites at the bottom.” The program came to an abrupt end when J. Edgar Hoover sent a memo calling for the termination of the breakfast program seeing it as a threat to their efforts to ‘neutralize’ the Panthers. The police raided the program on September 9th, 1969, while the children were being served.

The story of Yuri (Mary) and Bill Kochiyama is well known. In 1965, Yuri was on stage in the Audubon Ballroom in NYC on the day that Malcolm X was assassinated. The Kochiyamas raised their six kids in the Harlem projects, even sending them to “Freedom Schools”. Their apartment was a meeting house, a guest house, a drop-in center, a family hostel, a safe haven for freedom fighters.

Longtime Detroit activist and philosopher Grace Lee Boggs (1915-2015), author of American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Bogg (2014) and Living For Change (1998). She was a Chinese American married to James Bogg, a Black radical autoworker who wrote The American Revolution: Pages From a Negro Worker’s Notebook (1963). An important mentor, Grace made Nobuko promise to write her own story: “She had shared so much and pushed me in so many ways to use my creative process.”

With this sharing of her remarkable life, Nobuko has created a memoir that truly transcends any singular community or culture. She proudly speaks to the important role that Asian Americans had in the civil rights, anti-racism and social justice movements, something that is rarely ever heard about. There is so much to recommend this book.

Nobuko’s compelling writer voice possesses a humility and humanity that ultimately makes this such an exceptional work.

Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Song of Relocation, Race, Love and Revolution

By Nobuko Miyamoto

ISBN: 9780520380653

Publisher: University of California Press

344 pages, paperback, $29.95

www.ucpress.edu

© 2022 Norm Masaji Ibuki