Introduction: Kafu Nagai in Kalamazoo, Michigan

Kafu Nagai was the pen name of Sokichi Nagai, the author of Amerika Monogatari, a collection of short stories published in Japan in 1908, that was based on his experiences living in the U.S. for four years. In the book, Kafu wrote that while small groups of elite, educated Japanese with significant financial advantages had come to the U.S. and settled on the East Coast, the majority of the poor Japanese laborers and students who immigrated to the States ended up on the West Coast.1 Furthermore, he called the suffering West Coast Japanese an “ugly inferior race of Japanese,”2 plainly demonstrating his own class conscience and prejudices towards his own countrymen.3

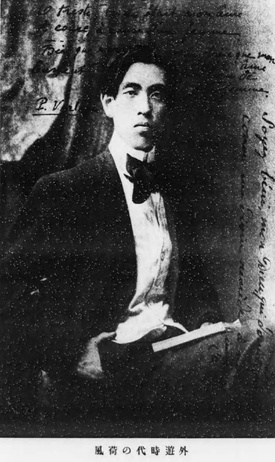

Kafu himself was born into an elite Christian family, and came to the U.S. in October 1903, when he was twenty-four years old. After a brief stay in Tacoma, Washington, he settled in the Midwest. It was as if he wanted to avoid both the Japanese elites in the East, as well as his “ugly” inferior countrymen on the West Coast. He visited the St. Louis World’s Fair in October 1904 and shortly thereafter entered Kalamazoo College in Michigan at the end of November 1904.

According to scholar Mitsuko Iriye, he must have felt much more comfortable once he moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where of course, there was no concentration of Japanese immigrants. A postcard written in English and sent to a friend in Tokyo described Kafu’s feelings; “I am very happy now in Michigan because I am treated no more as a ‘Jap’ (sic) as in Tacoma.”4 At Kalamazoo, Kafu was an “unclassified student” (auditor) studying English literature and the French language.5 His real name, Sokichi Nagai, was used for his student records at the college, which shows that the only classes he took in the fall of 1904 to spring of 1905 were First Year French.

Was Kafu really satisfied with his life in Kalamazoo, Michigan? He was an exceptionally sensitive and proud person and did not want to advertise the humiliation he had experienced living on the West Coast.6 It is possible that Kafu was not comfortable in Kalamazoo either, because he met a different type of Japanese there, different from both the elite Japanese on the East coast, as well as the “ugly inferior” Japanese on the West Coast that he detested. The type of Japanese he met in Michigan were people with the ability and capacity to be as competent as Americans and who were successful navigating the American system. An example of this third type of Japanese was a man named Katsuji Kato, who appeared to be a shining star, emitting a special aura.

Kafu rented a house with money provided by his parents, registered for only one subject at the college, and had to figure out how to kill time every day. In comparison, Kato, a Christian, worked hard to learn about and accept the American spiritual climate and system and to build a positive reputation. Kafu did not like Christianity, did not like being mistaken for an “ugly inferior Japanese,” and could not be an elite businessman like the people working in the New York branches of Japanese banks. His anxiety and self-disgust, due to his inability to find his own place in the U.S., must have been amplified in the solitude and boredom of country life in Kalamazoo.

Kalamazoo College was a well-known Baptist institution catering to young, pious Christian students in the upper Midwest. Literary scholars have recognized that Katsuji Kato, who always had a bible in his hand, fit in perfectly at the college, but that Kafu Nagai, who had completely different ethics and was already experienced with prostitutes found in red-light districts in his teens, was completely out of place.7

It is easy to imagine that Kato was a nuisance for Kafu, and that Kafu felt a sort of gloomy jealousy toward Kato. In fact, Kafu never said anything nice about Kato in his life.8 While feeling a sense of superiority towards the poverty-ridden Japanese at the bottom of American society, Kafu must have felt an inferiority complex after witnessing Japanese immigrants who were comfortable and competent around Americans, and wanted to entrap Kato. So Kafu “used” Kato for his own benefit.9 How? He created a character in one of his short stories who mercilessly ridiculed Kato.

Kafu’s short story, “Spring and Fall” in his book Amerika Monogatari, has three Japanese characters, two male and one female, and is set in K_ University, Michigan. Two of the characters, Taro Yamada and Kikue Takezato, are theology students. In contrast, Toshiya Oyama comes from a family of considerable wealth and arrives in the United States looking for women and dreaming about having sex with them. Bored with his life in Michigan, where there was nothing to entertain him, Kafu wrote in his story that Toshiya aggressively pursues naïve Kikue. After a while, Kafu writes, “Toshiya became as happy a man as he had long dreamed. This happiness was of the kind that only newly-weds enjoyed in secret gratefulness to God and to fate.”10

But before long, Oyama leaves Takezato and heads for more interesting experiences in the eastern U.S. After a few years, Oyama runs into Yamada again in Tokyo. By this time, Yamada has become a priest and married Takezato, who according to Yamada, had tried to kill herself in the Michigan woods during a snowstorm at night after Oyama abandoned her. Yamada tells Oyama,“Mr. Oyama. I am no longer blaming you for your sins at all.” To which Oyama retorts, “Well, at least it is clear that Christianity never causes harm to society,” and takes “a puff at the cigar he holds in his mouth.”11

In short, Oyama rudely insults the serious priest who chose to take care of the woman that he had used and abandoned. It isn't hard to interpret Oyama as a representation of the side of Kafu that had little respect for Christianity and that he wrote the story to make fun of and get revenge on Kato.

Katsuji Kato as scholar of theology

Katsuji Kato was born in Osaka in December 1885. His father was a very pious Christian who would not even walk near liquor stores.12 After growing up in a strict Christian family, he studied at Tokyo Gakuin (Duncan Academy) which was established by the American Baptist Missionary Union in 1895. After graduating in 1903, he taught at Wilmina Girls’ School in Osaka from 1903 to 1904 and left for the U.S. in June 1904, on the advice of a missionary in Japan.13 This missionary may have been Ernest W. Clement, an 1880 graduate of the University of Chicago and the first principal of Duncan Academy.

Kato entered Kalamazoo College in September 1904, two months before Kafu Nagai enrolled. He was eighteen years old. There were only 219 students at the college, and only two of them were Japanese: Kafu Nagai and Katsuji Kato. According to an article in the Kalamazoo College Alumnus, “Kato spent his first week in Kalamazoo at the home of Dr. Arthur G. Slocum, then president of the college.”14 Later he moved into a dormitory15 and studied hard his first year, taking classes such as Greek, German, Chemistry and Psychology, eventually becoming the first Japanese graduate of Kalamazoo College in 1909.16

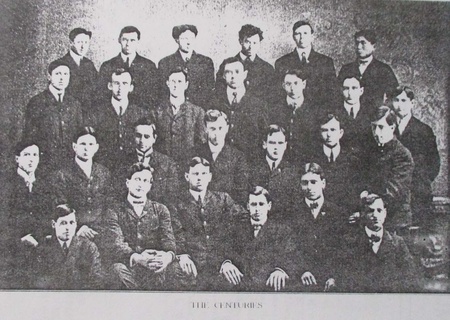

Kato immersed himself in extracurricular activities. He joined the Century Forum student club,17 where he made speeches on Japan dressed in kimono18 and shared his memories of celebrating Thanksgiving in Japan.19 When the club held a “Japan Day,” he read “The Moon-Maiden — A Japanese Legend” and sang Japanese songs.20 As Kato was also a talented artist, his drawings of swordsmen, women in kimono, and cranes in pine trees were printed in college publications such as The Kodak21 and The College Index.22

He was keenly interested in literature; Kato translated a short story written by Kenjiro Tokutomi, a Christian and key figure in Japanese literature, and published it as “A Dream” in the Kalamazoo Gazette in 1906 and then had it reprinted in New Thought.23

Kato also served as chaplain of the Century Forum club.24 Once Kafu Nagai left the college, Kato became the sole Japanese on campus, and had to apply himself with all of his energy when debates were held at Century Forum Club on themes such as “Resolved that the yellow peril is a menace to civilization” in January 1904, “Resolved that Japan in accepting the peace terms did herself an injustice” in 1905, and in discussions about the relationship between Japan and China in April 1906.25 Kato was one of the most popular students at Kalamazoo College26 and he was even invited to deliver lectures on Japan off-campus, in places such as Bronson, Michigan.27

After receiving his B.A degree from Kalamazoo College in 1909, Kato entered the Graduate Divinity School of the University of Chicago, with which Kalamazoo College was affiliated.28 In fact, to prepare himself, Kato had already registered at the English Theological Seminary at the University of Chicago while still attending Kalamazoo College.29 He majored in Religious Education and minored in Psychology at the Divinity School, joined the Japanese Club on campus, and soon was named the club’s secretary.30 He was also secretary of the Religious Education Club31 and a member of the Student Volunteer Band for Foreign Missions on campus.32 Kato enjoyed contributing illustrations to the Japanese Club’s pages in the school yearbook, Cap and Gown.

On the academic side, Kato earned his MA in 1910 with a thesis entitled “The Psychology of Sin: Its Significance to Religious Education,”33 his Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1911 with a thesis entitled, “The Socialization of the Child: A Psychological Study,”34 and his Ph.D in religious education in 1913 with a dissertation entitled “The Psychology of De-Ethnic Conversion: A Study of the Religious Experience of Some Japanese Christians.”35 That same year, he was given a chance to teach “Christianity in Japan” in the Missions Department at the Graduate Divinity School.36

While working on his degrees at the University of Chicago, Kato also got involved with the Japanese YMCI in Chicago, which had been run by Reverend Misaki Shimazu since 1908. He did translation work for the JYMCI37 and oversaw services after the Japanese Christian Church was established in 1914.38 In 1914, Kato left the University of Chicago for the next three years, returning to graduate school in 1917 to study physics, adding to his already impressive list of completed graduate-level degrees.39 When he left the divinity school, his teaching job in the Missions Department was taken over by Ukichi Kawaguchi, who received his Ph.D from the divinity school in 1914.40 Stepping into a new stage of his life, in February 1914, Kato married Koma Noguchi, a graduate of Defiance College in Ohio, atthe first Baptist church of Chicago.41 Their first son, Eimei, was born in Chicago in November 1914.

Notes:

1. Hibi, Yoshitaka, “Nagai Kafu Amerika Monogatari wa Nihon Bungaku ka,”,Nihon Kindai Bungaku Volume 74, page 100.

2. Sato, Mai, “Nagai Kafu Amerika Monogatari Ron: Natsu no Umi wo Megutte”, Showa Joshi Daigaku Daigaku-in Nihon Bungaku Kiyo, Volume 16, page 35.

3. Hibi, page 105.

4. Iriye, Mitsuko, “Amerika Monogatari no Yohaku ni Miru Kafu”, Bungaku, page 7.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Okuizumi, Eisaburo, “Hyoden: Shirarezaru Kato Katuji”, page 5-6, The Japanese Student and The Japan Review Explanatory Remarks, Iriye, Ibid, page 8.

8. Okuizumi, page 6.

9. Ibid, page 5.

10. Nagai, Kafu, “Spring and Autumn”, American Stories, page 65.

11. Ibid, page 67.

12. Okuizumi, page 5.

13. Kalamazoo College Alumnus February 1950, page 13.

14. Ibid.

15. Kalamazoo College Catalogue 1904-5.

16. Student’s Record.

17. The Kodak 1904-5, page 76.

18. The College Index October 1904, page 52.

19. The College Index December 1904, page 77-78.

20. The College Index May 1905, page 210.

21. The Kodak 1904-1905, page 86.

22. The College Index January 1905.

23. New Thought December 1906.

24. The College Index April 1905, page 186.

25. Strauss, David, “Kalamazoo’s Japanese Connection, 1900-1910”, Kalamazoo College Quarterly Fall 1985, page 27-28.

26. New Thought December 1906.

27. The University of Chicago Weekly July 12, 1907.

28. Chicago Record November 20, 1895.

29. Annual Register 1907-1908.

30. Cap & Gown 1912.

31. Cap & Gown 1911.

32. Cap & Gown 1910.

33. Annual Register 1909-1910.

34. University of Chicago Convocation Program June 13, 1911.

35. University of Chicago Convocation Program June 10, 1913.

36. Annual Register 1913-1914.

37. Chicago Tribune December 27, 1913.

38. Report of Misaki Shimadzu, August 1915, YMCA of Chicago Japanese Department Collection, Chicago History Museum.

39. Annual Register 1914-1915, 1917-1918.

40. Annual Register 1914-1915, pages 385, 711.

41. The University of Chicago Magazine, March 1914.

© 2022 Takako Day