Warren Nishimoto retired in 2017 after 37 years as director of the Center for Oral History at the University of Hawai‘i. During the nearly four decades of his leadership, the Center produced over 850 interviews focusing on the working class in Hawai‘i. He is quick to acknowledge that the arduous and precise work of interviewing subjects and transcribing the interviews was spearheaded by master researcher and interviewer Michiko Kodama-Nishimoto, his wife, and longtime staffers Cynthia Oshiro, who transcribed the majority of the interviews, and interviewer and researcher Holly Yamada.

Family Roots

Nishimoto’s maternal great grandfather, Matsukichi Iida, was the founder of the S. M. Iida Store in 1900. For more than 100 years, the store had been a mecca for unique Japanese goods in Hawai‘i. His son, Koichi, a pillar in the Japanese community, was part of a hui that established the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and started Central Pacific Bank. After Dec. 7, 1941, Koichi was incarcerated at a series of camps on the continent including Lordsburg, Livingston, Missoula and Santa Fe. In Koichi’s absence and his wife’s passing, Nishimoto’s mother, Yoshiko, helped care for her younger siblings, and her husband, Tsuyoshi, managed the store.

Born in 1949, Nishimoto recalled fond childhood memories of spending time at the store and playing among the packing crates. As he grew older, he felt the tug and pull of living in two very different worlds at home and at school. He said, “I grew up in a very traditional Japanese family. Grandfather was the shogun. Everyone waited on him. And then I had this strong American culture at school and in the neighborhood.” Nishimoto also realized that his father hoped that he would take an interest in the store and someday assume management of the Iida enterprise.

Searching for New Paths

Nishimoto, however, had other ideas. He felt a strong need to break away from his traditional home environment and the pressures of becoming part of the Iida business. This led him to seek colleges on the mainland after he graduated from the University Lab School. He received a bachelor’s degree in American history from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1972 and a master’s degree in international studies from the University of Washington in 1977.

Returning home, Nishimoto was not sure of jobs a history major might pursue. In 1978, when he saw an opening for a researcher at the UH Ethnic Studies Oral History Project, he took a chance and applied. At the interview, he met Michiko Kodama, who was trying for the same job. Luck was with him when the project director, Chad Taniguchi, decided to split the job and hire both of them. Working together sparked a romance that led to their marriage in 1984.

Joining the Oral History Movement

According to Nishimoto, the 1950s through 1970s were pivotal decades that saw the rise of oral history as a legitimate form of historical documentation. As far back as the 1940s, Allan Nevins, a political historian at Columbia University, pioneered piecing together history through primary sources found in archives and letters. Nevins was the first to use tape recorders to preserve memory.

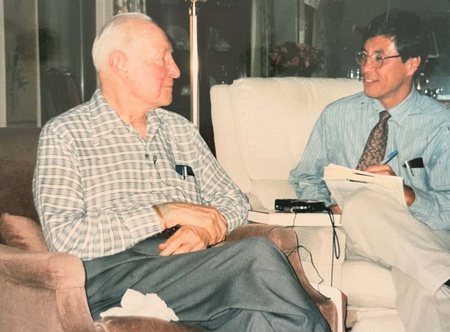

In Hawai‘i, the staff at the Oral History Project wanted to capture the stories of the common workers. Nishimoto explained, “Up till then, the plantation histories were largely written by former white managers. To have retired workers recall not only what they did but why they did it, how they did it, what life choices they made, why they came here in the first place, all of that was exciting.” The staff established systematic collection protocols by organizing their resources according to geographic areas, ethnicities, and occupations.

They originally conducted the interviews with tape recorders, then transferred them to reel-to-reel tapes in an attempt to extend the life of the interviews. The edited transcripts were bound in printed volumes with subject indexes and made available through the Hawai‘i State Public Library System. Today, digitized transcripts of many of these resources are available on the UH ScholarSpace, which is an open-access, digital institutional repository for the UH Mänoa community.

Gaining Recognition and Acceptance at UH

The Oral History Project was established in 1976 by the Hawai‘i state legislature as a grant-in-aid to the ethnic studies program at UH Mänoa. Legislators like Richard Kawakami, Yoshito Takamine, Mamoru Yamasaki and Ken Kiyabu, with roots in working-class families, supported the project with separate annual funding from 1975 to 1983. When Nishimoto assumed the project’s directorship, David Hagino, who was chairing the House Higher Education Committee, told him that the project should be part of the existing UH budget plan.

The issues, however, were complex. The project was connected to the ethnic studies department that was associated with controversial local protest movements such as Save Kalama Valley and People Against Chinatown Eviction. The UH administration did not want to expand funding for the department. Nonetheless, legislative supporters pushed through a bill in 1984 including the project as part of the Social Science Research Institute budget. Importantly, this established four permanent positions for the Center thereby ensuring its survival. Although administratively under SSRI, the Center maintained a working relationship with ethnic studies department. The name was also changed to the Center for Oral History.

The battle for legitimacy, however, was far from over. The notion of oral history as a bonafide form of scholarship was met with strong resistance from academic segments of the UH community. Nishimoto said, “The history department at UH maintained that oral histories were not real history. They called it hearsay.”

Over time, academicians have come to view oral histories as a viable means of capturing community stories by asking who owns these histories and how that ownership is manifested. They now realize that these stories do not supplant more conventional records of history but that they help us to understand how individuals and communities have experienced the forces of history.

Work at the Center

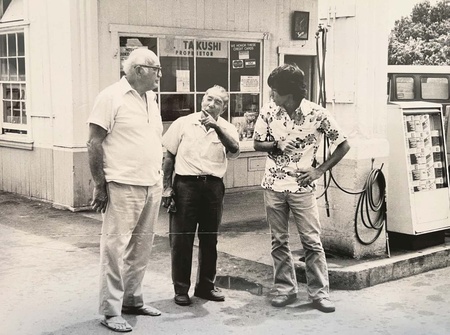

When he first started, Nishimoto admitted that he didn’t know how to conduct these interviews. One of his first assignments was to talk to storekeepers in the Pä‘ia and Pu‘unene regions on Maui. These were Issei who wanted to escape plantation work. Nishimoto practiced at the project offices in Mänoa Elementary. He remembered doing an interview with the school cafeteria manager and learning the important skills of being a good listener and being naturally inquisitive.

He noted that the tone of oral histories changed between the stories told by first- and second-generation subjects. When they interviewed Issei in the 1980s, they heard very difficult narratives. He recalled, “They were harsh stories about good as well as bad relations with employers and co-workers.” In contrast, the anecdotes shared by second generation Filipinos, Puerto Ricans, Portuguese and Japanese were nostalgic recollections of small-kid time on the plantations. Nishimoto noted, “They talked about fishing in the streams and climbing trees. They described picking mango, bringing their own shoyu, mixing it with sugar, dipping the green mango and eating it.”

Nishimoto earned a Ph.D. from the UH Educational Foundations Department in 2002 by completing a dissertation based on one of the Center’s memorable histories of the 1946 tsunami in Hilo.

The Center’s Achievements

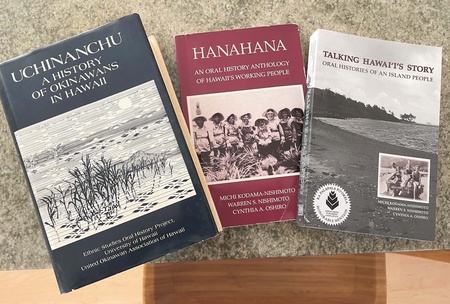

A singular achievement for the Center was the publication of Uchinanchu: A History of Okinawans in Hawai‘i. Published by the UH Press in 1981, this book was a groundbreaking accomplishment that melded traditional records of history with interviews. Requested by the Hawaii United Okinawa Association in celebration of the 80th year of Okinawan immigration to Hawai‘i, the book centered on oral history interviews with the working class. Nishimoto reported that the community response was tremendous – the first run of 5,000 copies sold out even before distribution.

Another notable publication in 1984 was Hanahana: An Oral History Anthology of Hawai‘i’s Working People, which showcased some of the best interviews conducted by the Center. It featured narratives of twelve working people and captured how they felt and lived. Reviewers of the book praised the anthology for “enriching our understanding of workers in twentieth-century Hawai‘i.”

In 2009, the Center published its third book, Talking Hawai‘i’s Story: Oral Histories of an Island People in collaboration with the UH Center for Biographical Research. This was a collection of 29 oral histories that captured life in territorial Hawai‘i ranging from communities in Honolulu to those in Kona and Lana‘i. The anthology preserved Hawai‘i’s social and cultural history as viewed by workers, neighbors, and families.

Nishimoto has been especially proud of the Center’s work with groups interested in conducting oral histories. They have held training sessions for schools, churches and various community agencies throughout the state, as well as at centers on Guam and American Samoa. “One of the most satisfying things was to do a workshop for a group and have them complete a project. They would show me the final product, like a book or a documentary. That really warmed my heart.”

Reflecting Forward

Nishimoto is proud of the Center’s accomplishments. He said, “We kept the project funded and well-respected in the community. We were an important part of the University of Hawai‘i as well as the national and international oral history movement.”

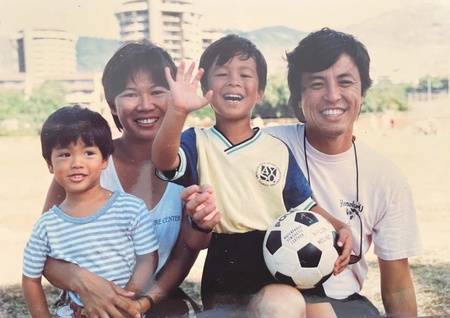

He continued, “The majority of our interviews looked at diversity as a positive thing. Even in these contentious times, people are proud of the fact that we do have some measure of racial harmony.” He indicated that Hawai‘i’s growing ethnic diversity is moving us from a focus on group-centric racial identity to an increasingly multiethnic perspective. He cites his two grown sons as examples of a generation that no longer defines itself by a single ethnicity. He is happy that they are both engaged in careers and interests that mirror their social consciousness and social activism.

At this point, Nishimoto sees himself as part of the age group that a younger generation might interview. In short, he has become part of the community’s story. He wants to see this happen at the Center, which is now under the directorship of Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor. “Hopefully, they’ll hire young interviewers and researchers to interview people like us, about our experiences.” Sustaining this legacy will ensure that future generations learn about the past from the compelling spoken stories of the people who lived through them.

Note: This series, “Honoring the Legacy,” is a partnership between The Hawai‘i Herald and the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i. It celebrates the achievements of Japanese American men and women who live the values of earlier generations and continue their proud legacy. The complete interview with Warren Nishimoto is available at the JCCH Tokioka Heritage Resource Center. It can also be read online.

*This awas originally published in the Hawai'i Herald on November 18, 2022.

© 2022 Melvin Inamasu and Violet Harada