It was a warm summer day in August 2022, but I could feel my feet and hands growing colder, a scratch in my throat developing. I was sitting at my youngest daughter’s desk while she was trying to sleep. My husband and oldest daughter had contracted COVID-19 and were isolating in our basement. Some sunlight was reaching into my daughter’s bedroom over my left shoulder while I sat at her white laminate IKEA desk. I could feel myself almost getting sick with an infection of some kind, but it never developed into a full illness. I think I stopped just in time. But I knew I was deep in powerful emotional terrain, and if I was not careful, I would drain my own immune system.

I was writing the text for an exhibit that would open in October 2022 at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle. For readers who might not know the Wing, it’s a special place—the only pan-Asian American museum in the United States—and it’s housed in buildings repurposed from the early development of Seattle’s Chinatown/International District. The Wing works through a groundbreaking advisory process, taking time and several meetings (at least) to develop visions and goals with a community advisory committee for each exhibit.

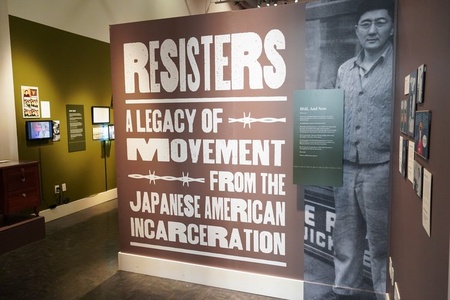

I was gratified that by suggestion of committee members, the Wing’s exhibit developer Mikala Woodward asked me to write the text for his exhibit. The title is Resisters: A Legacy of Movement from the Japanese American Incarceration. Inspired by We Hereby Refuse, the graphic novel that I co-wrote with Frank Abe and illustrated by Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki, “Resisters” is a homage to Japanese American resistance and a challenge to museum visitors to examine their own reactions to history and injustice. It includes powerful artwork by contemporary Japanese American artists, including Ellen Bepp, Kiku Hughes, Lauren Iida, Michelle Kumata, Erin Shigaki, and Na Omi Judy Shintani. It also includes artwork by my dear friend Anida Yoeu Ali, who is Muslim Khmer with roots in Cambodia, Chicago, and Tacoma. Rare artifacts are also in the exhibit, including a CARP first-run edition of John Okada’s No-No Boy, and a signed Day of Remembrance poster on loan from Frank Abe, and videos and community photos illustrating different parts of our history, including resettlement and protest.

The writing challenge, as I would come to understand it, was to write about 12 panels of text. Each panel could be no more than 250 words encapsulating some aspect of the incarceration, responses (including compliance and resistance) to the incarceration, living conditions in camp, resilience in camp and afterwards, redress history, the model minority myth, and parallels to other communities responding to injustice. The panels would be on the walls as a way to guide viewers through the four rooms and hallway of the exhibit. For each panel I had a paragraph or list of bullet points that the advisory committee wanted to include.

I had to write with deep humility, knowing that many visitors might not read the text at all. But I wanted to be another artist on the wall, joining forces with the other artists.

To do this I called on all my public history knowledge and skills. I knew I wanted the words to stand in solidarity with the artwork. I wanted to address the viewers directly, possibly shaking them out of a passive interaction with the exhibit. Resistance is a form of response, and I wanted to immerse readers as much as I could in the factors which would dictate different responses. I talked over this non-traditional form of the exhibit text with Mikala, and she agreed that I could take this approach.

Somewhat to my surprise, my training in poetry really came to the fore. In my numerous poetry classes I learned how poetry can be all about condensed imagery and concentrated emotion, all set to a rhythm that feels like music. And it felt like I was writing poetry most of the time, or perhaps “micro essays.”

It is hard to condense history into vibrant words that will grab readers. For example, the main book I read for an overview of redress history by Alice Yang Murray, is over six hundred pages. I could only use about two hundred words. So: poetry.

As I worked on the panels during the summer of 2022, I could feel so many of my previous public history and arts projects at work in this one: the graphic novel, the permanent exhibit Tanforan Incarceration 1942, the catalog essay I wrote a few years ago for NaOmi Shintani’s installation “Dream Refuge” (the installation is part of the Resisters exhibit at the moment), the articles for HistoryLink that I’ve written, the personal essays I’ve written here for Discover Nikkei.

In my head I was walking through the museum rooms, since I’d visited the museum many times before. I had electronic previews of the artwork in a shared folder, so I had to mentally install those on the walls in my imagination.

Rather than using an objective, third person point of view to the exhibit text, I chose to use a combination of “you” (second person) and “we” (collective third person). I thought of Julie Otsuka’s novels, and how they use that shifting point of view in order to address readers directly. I also thought about Gloria Naylor’s wondrous novel Mama Day, which uses “we” like a Greek chorus to comment on the action of the book. These points of view tend to involve readers in ways that can feel visceral, immediate, and intimate, and those were the kinds of feelings that I hoped the exhibit text would evoke. I did not want to explain the story of the incarceration yet again; I wanted viewers to feel and see how Japanese Americans and others have responded to history.

Though we did not include footnotes in the exhibit text, almost every line on the larger panels is keyed to something else: to a specific person, a passage from the graphic novel, a historical incident, a detail from my family history, a fact that I had gleaned during my years of research, a friend’s story that I’d heard of briefly. When I got to meet Kiku Hughes for the first time in person at the opening reception, I told her about the line keyed to her graphic novel Displacement: “You learn to travel through time and space.”

The quotations that I use in the exhibit are from Dr. Donna Nagata, Dr. Satsuki Ina, and Nobuko Miyamoto—all women warriors in the Japanese American community who have done deep healing research and activism. I wanted to be as inclusive as I could, while also writing the text as an offering to those who have resisted.

When I finally got to see the panels installed, I was excited to see that the graphic designer did not print the panels with black text on white backgrounds—the typical museum signage that visitors tend to ignore. Instead, they made the panels a dark sage green, with white text, with a barbed wire graphic across the bottom of each panel.

I’m grateful to the exhibit team (including Senior Exhibit Developer Mikala Woodward, Exhibit Director Jessica Rubenacker, and Deputy Executive Director Cassie Chinn of the Wing Luke Museum for their support with this work.

And I’m so proud to be part of this exhibit, which honors these contentious stories of resistance in Japanese American history.

If you’re in the Seattle area or visiting, please consider visiting the Resisters exhibit while it’s up from October 2022-September 2023.

* * * * *

At the opening reception, Wing staff asked me to speak briefly about my motivations for writing the text. What emerged is this speech, lightly adapted:

In memory of Junichi Fred Nimura, Issei, my grandfather. First Issei to be arrested from within Tule Lake for speaking out, taken to Klamath Falls jail in Oregon, Sharp Park temporary detention facility in California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico Department of Justice internment camp. In memory of Shizuko Okada Nimura, my grandmother, who raised six children behind barbed wire.

In memory of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Nisei, my uncle. Poet, playwright, librarian, actor, activist. No-no boy at Tule Lake concentration camp. Renunciant. A key figure in our graphic novel We Hereby Refuse, whose pages you will see here.

In memory of Taku Frank Nimura, Nisei, my father. Librarian, actor, poet. Ten years old at Tule Lake. I lost him when I was ten years old myself. In memory of my oldest aunt, Hisa Nimura Horiuchi, who supported her siblings inside and outside of camp.

For my Nisei aunts and uncles still living: Nobuya Nimura, Sadako Nimura Kashiwagi, Tomiye Nimura Sumner, Shinobu Nimura Alvarez. You will hear my auntie Sadako’s voice as part of Na Omi Shintani’s artwork, and so her story and my uncle’s are together in this exhibit.

In memory of Mitsuye Endo and Jim Akutsu. In memory of Minoru Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Korematsu. In memory of the Fair Play Committee and the resisters of Heart Mountain.

In memory of the DB Boys, of the Mother’s Society of of Minidoka.

In memory of Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and Michi Weglyn and Yuri Kochiyama.

For 125,284 persons of Japanese descent. For those who were incarcerated, those who have left us and those who remain with us.

For the descendants. For my daughters.

For the redress warriors past—and present.

For the artists.

For the allies.

For those with whom we stand in strong and joyful solidarity.

This exhibit is an offering to you all, a conversation with you all, a challenge for you all. We honor you all here.You all give us the strength, the courage, and the inspiration to resist.

© 2022 Tamiko Nimura