Preserving a Way of Life of Their Native Land

My curiosity was piqued by a video interview by Barbara Kawakami, author of the book Picture Bride Stories. It featured my aunty Matsue Shimabukuro who is originally from Wahiawä. She reflected on her shimpai (arranged) marriage with Uncle Takeo Shimabukuro from ‘Aiea. That arrangement was made by their Issei parents who were members of the Aza Yogi Doshi Kai.

How my parents met was a question that lingered in the back of my mind. My dad, Seiei Nakasone, was from Wahiawä and my mom, then Masae Miyasato, was from ‘Aiea, like Aunty Matsue and Uncle Takeo. Was that a coincidence?

I asked my uncle Satoru Nakasone, my dad’s younger brother, if they had a shimpai marriage. He said they did. My dad’s sister, Aunty Sueno Murakami, who is 93-years-old, confirmed it saying, “Baban (my grandmother, Kamei Nakasone) wanted your mom to marry your dad because her family came from the same tokoro (place) in Okinawa and same Yogi club.” She said, “Baban always had an eye on your mom to marry your dad. Back then, you listen to your parents.”

According to the book, Uchinanchu – History of Okinawans in Hawai‘i, marriages between residents of a different son (village) in Okinawa were “unthinkable.” Even marriages between residents of two aza (hamlets) within the same son were firmly resisted. It was based on the ground that the groom was taking away a woman, a reproductive element, from the bride’s community. That was the doctrine going back generations that Issei parents were adhering to.

The club gatherings such as the annual shinennkai (New Year’s) dinners and summer picnics were matchmaking opportunities for Issei parents. My grandfather, Jiro Nakasone, along with three Nakasone relatives; Matsukichi Nakasone (Matsue’s father), Yeiso and Yeison Nakasone, were early organizers of Aza Yogi Doshi Kai. And with my mom’s parents, Yamazou and Ushi Miyasato, being Aza Yogi club members, I understand why my parents may not have had a say. But as it turned out, my Baban could not have made a better choice, and they got married in March 1949.

My dad and Aunty Matsue were first born, their younger siblings were not subject to a shimpai marriage based on place of birth. That practice could not survive in a modern Western society.

A shimpai marriage by Issei club members was new to me. It spoke of the old ways. What else is there to learn about these clubs?

Historical Background

The early inhabitants of the Ryukyus (Okinawa archipelago) led a primitive lifestyle centered on fishing, hunting, and gathering. The archipelago provided an abundance of ocean resources and a hospitable subtropical environment. And the results of a study by the Zoological Society of Japan strongly suggest that the ancestral form of the Ryukyu wild boar existed on the archipelago prior to the arrival of prehistoric humans. The first Ryukyuans had the means to prosper.

Like most early societies, Ryukyuan people transitioned to cultivating crops. According to the book, The Ryukyu Kingdom – Cornerstone of East Asia, this marked the beginning of the gusuku (castle) period, which is estimated to be sometime in the eleventh or twelfth centuries.

It was during this period when agricultural villages started to form, each within recognized geographical boundaries and usually populated with people related by blood or marriage. A leading class known as aji (lord) emerged in every village during this period. Early on, the aji would build a gusuku (stone enclosure) to mark his political power. When the village became overpopulated, the aji would assign family groups to start a farming community in a new area within the boundary. These communities were self-sustaining and autonomous.

Interviews with Issei further revealed when they were growing up in Okinawa in the late 1800s and early 1900s, generations would live in isolation in these farming communities. There was little contact even between the nearest neighboring aza within the son. Poor roads and the lack of transportation kept the local communities isolated from one another. Long distance travel was rare and if it was necessary, it was likely by foot.

They had long-held local traditions and a culture centered on community. When a family was in need, others were there to help. Their way of life forged a deep kizuna (bond) between them. The clubs in Hawai‘i attempted to preserve that way of life from their native land. The club was like a refuge in a strange land with diverse ethnic groups and languages. It was a social support system that provided them a level of comfort and security.

Wahiawa Okinawa Kyo Yu Kai

The families of the three Nakasone Issei relatives, Jiro, Matsukichi and Yeiso, who settled in Wahiawä, have been members of the Wahiawa Okinawa Kyo Yu Kai (WOKYK) for three generations. As a contributing writer for this publication, when interviewing people, I would often be asked, what club do I belong to? (It’s like what we ask in Hawai‘i when meeting another local the first time: “What high school you went?”) I would answer: “My family belongs to the WOKYK.” I personally was not a member then but had become one out of guilt.

The book Uchinanchu further states that WOKYK is considered an “all-Okinawan” club as compared to a “locality” club, based on place like the Aza Yogi Doshi Kai. Wahiawa Okinawa Kyo Yu Kai was established in 1937, and back then, Wahiawä was a small pineapple plantation town and considered in the “boonies.” The Okinawan population was relatively small to establish “locality” clubs. At that time, all Okinawan clubs that were formed in Honolulu lasted only a few years while locality clubs thrived. One might say, Wahiawä, being a small pineapple plantation community and somewhat isolated, WOKYK became their version of a locality club.

Upheaval of WWII

Many of the Okinawan clubs were formed in the 1920s and 1930s. They were thriving until the attack on Pearl Harbor. All clubs representing prefectures from mainland Japan as well as Okinawan clubs were shut down. Records were destroyed and financial assets were donated to support the U.S. war effort. There was fear of prosecution against the Japanese community. These actions were to demonstrate that Japanese Americans were loyal to their country.

Wahiawa Okinawa Kyo Yu Kai records were destroyed by club secretary, Tomonori Oshiro, and the club went dormant. It wasn’t until 1950, that the first organizational meeting to revive the club was held. It was hosted by Thomas Shigeru Miyashiro at his home on the grounds of the Wahiawa Botanical Garden, where he was the superintendent.

He had just relocated from Foster Gardens in Honolulu that year. His daughter, Mildred Arakaki, now 85-years-old, recalled as a young girl helping to serve snacks at the meeting. She said, “the district representatives were there.” She recalls that Raymond Inafuku, Jiro Nakasone, Sonkyu Iha, Soei Aniya, Horace Higa, Shigeru Chinen and Shigeru Nakamura all showed up. She said, “Grandpa was instrumental in reviving the club.”

Wahiawa Okinawa Kyo Yu Kai was re-established in 1951, roughly six years after WWII ended. My grandfather, Jiro Nakasone, assumed the role of president.

Post-WWII Relief for War-Torn Okinawa

The post-WWII relief effort for war-torn Okinawa accelerated the revival of some clubs. The people of Okinawa were in dire need and the motivation to send supplies was at a fever pitch. The clubs provided an established network to mobilize people on short notice.

A club was born out of the relief effort. Rev. Masao Yamada of the Holy Cross Church in Hilo recognized the effort by a group of volunteers who mobilized to collect supplies that were stored at the church. He recommended that they continue to work as a group for betterment of the community. Thus, Hui Okinawa (formerly Hui Hanalike) of Hawai‘i island was established in November 1946.

Moving Clubs Forward In the 21st Century

As a Sansei, I’ve heard the concern of attracting the Yonsei. Getting the younger generation interested was also a concern for the Nisei.

As quoted in the book, Sonsei Nakamura of Haebaru Sonjinkai explains: “We Nisei have had contact and communication with the Issei so we were inclined to join the club. With the Sansei, it is another story. The younger ones are drifting further and further away from the organization; however, we are trying very hard to get them interested in the club.”

One might surmise that this will be an ongoing concern with each new generation. The following points are in general terms and based on oral history published in “Uchinanchu,” feedback from club members, personal observations and data from the 2019 Okinawa Festival.

- “Life-stage” is a fundamental reason why club members are older. Today’s career demands while raising young children leave adults with little time for outside activities other than with their families. As their children get older or when they leave home and become independent, more time becomes available. And it’s at this life-stage where we may take more interest in our family’s history, our heritage and cultural identity.

- A proven practice on recruiting members is reaching out to people in your social circles. Personal relationships and shared values are key to recruiting and retaining membership. And as clubs today have many non-Okinawans members, club leaders could consider recruiting people who are Uchinanchu-at-heart.

- “Today’s society with all its distractions makes it more of a challenge to recruit young people. Social trends constantly change, and club leadership need to be aware and adapt.

- “When young people get involved, older members need to be open to new ideas to move the organization forward. In turn, meaningful contributions by young people will help to retain them. With positive outcomes, they’ll be more invested. (Not all outcomes will have the desired results, but we learn from them.)

- “Older members could mentor young members with leadership ability and share their institutional knowledge.

- “Majority of millennials and Gen Z want to make a positive difference in the world. According to Inc. Magazine, 84% of millennials say making a difference is more important than professional recognition. Community-service projects that are important to them may be an incentive for them to get involved.

- “When we consider that these clubs were an extension to the Issei’s way of life in their native land that may date back centuries, that is an incredible legacy to let drift away.

My Childhood Memories of the WOKYK Shinennkai

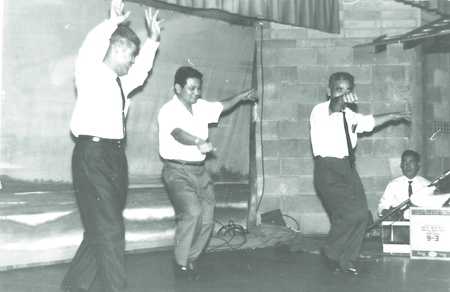

Member talent shows were a big part of the entertainment at the annual shinennkai parties. As a young boy, I fondly recall the Nakasone trio with my mom on harmonica, Uncle Yeiko Nakasone on guitar and my dad singing. They played “You are My Sunshine” to an appreciative full house at Dot’s banquet room in Wahiawa.

My dad loved to sing, and he would go on stage solo and sing songs acapella. His favorite was the iconic Irish song, “Oh Danny Boy.” I didn’t know it was a popular song of the time – I thought he was singing about me. I felt embarrassed and rushed out of the banquet room and peeked through the door to watch him sing.

If I could relive that moment today, I would join him in a father and son duet.

*This article was originally published in The Hawaii Herald on October 21, 2022.

© 2022 Dan Nakasone