“Let me microwave something real quick.”

It seems fitting that this is the first thing Gil Asakawa says to me before we start our phone interview. His wife Erin has made him a soup of nori, tofu, ground turkey, and green onions from their garden. It’s only 10:30 a.m., but to him this is “lunch-ish.” Breakfast was some leftover ribs from the night before. “We have very eclectic dining patterns,” he explains unapologetically.

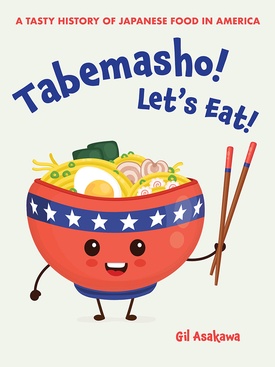

This prologue to our conversation is fitting because we’re about to discuss Asakawa’s just published book, Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!: A Tasty History of Japanese Food in America. It’s an informative, accessible, and joyfully nostalgic look at the rise of Japanese food in America, filtered through Asakawa’s unique lens as a child born in Japan but raised in the U.S. from the age of eight.

“I was interested in writing about the food I love and the food I grew up with,” he explains. “I enjoy the fact that when I moved to the U.S., Japanese food was considered weird, sushi and sashimi were gross—and now it’s available at the supermarket. I’m sure the grandkids of the third-graders who teased me back then are eating sushi three times a week, and probably not very good sushi.”

To capture that rise in Japanese food’s availability and reputation, Asakawa tells the story partly through his own coming of age story and partly through historical research. References abound, to movies and television series like The Breakfast Club, The Wonder Years, or the book and movie Shogun. As a former art and rock music critic and entertainment writer, those come easily to him, and firmly locate the Japanese foods Asakawa describes in a shiny, commercial, and very American pop culture landscape.

The book was also a follow-up to Asakawa’s book, Being Japanese American: A Sourcebook for Nikkei, Hapa … & Their Friends, published in 2004. He revised the book in 2014, which was also about the time he began taking pictures of food and sharing them on social media—something that as Asian Americans we feel we have a special license to do. “I kind of realized that I’ve always been a foodie,” he says, and that the time might be right for a book on Japanese foodways in America.

Asakawa structured the book like a menu, with the first “appetizer” chapter introducing the basic building blocks of Japanese cuisine: dashi, soy beans, soy sauce, and MSG. The next, “first course” chapter delves into the three iconic Japanese dishes that first broke through in America: sukiyaki, teriyaki, and tempura. The hot pot dish sukiyaki, a mix of thinly sliced beef, tofu, napa cabbage, and shirataki noodles, is said to have originated when farmers used their spades to grill meat and vegetables together, and the oldest sukiyaki restaurant in Tokyo dates back to 1869.

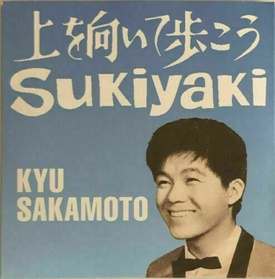

Most interesting to me, though, is the story behind the 1960s Kyu Sakamoto cross-over hit “Sukiyaki.” While the song’s English named was slapped on by a British producer who happened to like sukiyaki, its Japanese title, “Ue wo muite/I look up” comes from a line in the song, “I look up so my tears won’t fall.” Far from being a lament over lost love, which is what I always assumed, however, the tune reflects its Japanese songwriter’s deep sorrow over a failed protest against the continued presence of American troops in Japan after World War II.

Tabemasho! also includes chapters on sushi; udon, soba, and ramen noodles; rice dishes, and desserts ranging from manju to mochi ice cream. In a chapter on JA ingenuity and adaptability, Asakawa describes how, even when they were imprisoned in U.S. government World War II concentration camps, inmates were able to grow soy beans to make tofu and miso. Some even made hydrolyzed vegetable protein to create the umami of shoyu without fermentation.

And he tips his hat to the ingenious Takaki family of Pueblo, Colorado, who marketed a delicious product called Karami salsa, which captured the local JA tradition of swapping roasted green chiles for wakame seaweed in tsukudani (a dish of shoyu-simmered meat or seafood). The product was carried at local grocery stores and became an all-purpose condiment, a Japanese twist on Mexican salsa. In a chapter on beverages, Asakawa catalogs the outer fringes of the carbonated drink Ramune, which include flavors like chili oil, curry, octopus, and corn potage.

In the last chapter, or “Next Course,” Asakawa addresses the hot-button topic of authenticity versus appropriation. He has never been able to accept the California roll, in part because of the way his mother’s pejorative description of it as inchiki sushi, or “fake” sushi still rings in his head. Nor will he touch Americanized sushi inventions like the Dragon Roll (another “inside-out” roll involving avocado and shrimp tempura). Yet Asakawa says his views on the topic of appropriation have mellowed over the years.

The process of writing this book has brought with it the realization that “cuisine is an ever-evolving cultural process,” Asakawa says. “You can be based in tradition and still embrace the fact that you’re in the U.S. and don’t have access to certain things, so you might as well incorporate other ingredients.” But he adds that it still bothers him when people “rip off a tradition,” making purportedly Japanese dishes that are outright bad.

Asakawa also points to some up-and-coming Japanese foods that are having their moment (furikake, robata-yaki, okonomiyaki, and the Japanese sando). Others, he predicts, will never be embraced by Americans: whale meat, natto, and karinto, a sweet cracker that he liked to call “cat poop” as a child because that’s what it resembles.

His mother, Junko Asakawa, he admits, was a huge influence on his love for Japanese food. “I was the foodie, even as a kid. I used to watch how she cut vegetables, listen to the sound of the hocho hitting the wooden cutting board.” A Hokkaido native, she loves salmon and will shun expensive matsutake mushroom for the mushroom she grew up with, shiitake. She is also proof of how deeply an enduring love for one’s native foods can run. Even though she has dementia, lives in a memory care center, and doesn’t recognize her three sons, she will eat her favorite dish, chirashizushi, in the same order that she has always eaten it: “salmon first, then tuna, then one of the eggs. She’ll put other egg aside, by the end, she usually give us the extra egg,” says Asakawa. “Someplace deep in her brain’s hard drive that memory is still there.”

“Research” for the book did involve eating lots of Japanese food (“I had to take one for the team,” Asakawa deadpans), though because of pandemic lockdowns it was not as far-flung as he would have liked it to be.

Asakawa’s other great food influence is his Yonsei (fourth-generation) wife Erin Yoshimura and her extended family. While his family’s New Year’s celebrations were small affairs, the Yoshimura family’s celebrations are extravaganzas that cover four tabletops, “with everything from traditional kuromame (black beans) with a sign telling people to eat odd numbers for good luck, to Spam musubi, every side imaginable, and Korean twice-cooked ribs,” he says. He dedicates the book to Erin’s late father Rex Yoshimura, whose prodigious memory for great food and long-closed restaurants enabled him to “name the best dishes at every current and past favorite eatery.”

The infiltration of Japanese food into every corner of American life is something Asakawa looks upon with pride, and a sense of vindication. The Northern Virginia kid who felt embarrassed when his jock friends would come to his house and be assaulted by the “gross” smell of simmering oden or frying salmon now revels in how those foods have multiplied beyond his wildest dreams, and become mainstream.

The book is guaranteed to make you hungry for Japanese food. At its end, Asakawa transforms from guide to host. As if inviting the world to the dinner table with him, he completes his tale with an exhortation to sit down and dig in: “Itadakimasu! Tabemasho!”

* * *

Join Gil Asakawa and Nancy Matsumoto on Tuesday, October 25, 2022 at 5 p.m. (PDT) for Nima Voices: Episode 10—Gil Asakawa! They will chat about Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!: A Tasty History of Japanese Food in America, his participation in Discover Nikkei’s multilingual food program, and more! The interview and Q&A will be livestreamed on the Discover Nikkei YouTube channel or on Facebook. Make sure to log in so you can post your questions for Gil.

© 2022 Nancy Matsumoto