Unfortunately, after World War I, the tide began to turn for Japanese performers. In February 1922, just before the Immigration Act of 1924 completely barred further immigration from Japan, Consul Kuwashima in Chicago reported to Foreign Minister Uchida as follows:

“Peculiar and specialized Japanese entertainers such as singers of Naniwa bushi and biwa players, Rakugo performers, and others cannot earn any profit for performing. Nevertheless, Japanese acrobats still can be seen sometimes performing in theaters run by Americans, but their performances are rather inferior in comparison with the Westerners’ performances. Therefore, it will not be favorable to encourage entertainers to come to America and tour in the various towns in the territory of the Japanese Consulate in Chicago.”1

Even after immigration from Japan ended, Consul Ohashi in Los Angeles complained to Foreign Minister Shidehara in Tokyo that many entertainers were coming to the U.S. due to the recent depression in Japan, that recruiters targeted poor Japanese immigrants, that entertainers were generally of low class, and that some female performers were found to have seduced single men on the West Coast, swindling them out of their money.2

Because entertainers had such a difficult time obtaining permission from the Japanese government to enter the U.S., the number of Japanese entertainers in Chicago obviously declined from what it had been before the end of World War I. Entertainers made up 3.8% of the Chicago Japanese population in 1900, 5.1% in 1910, and 3.8% in 1920. In 1930, there were only seven performers listed, including Kaichi Koban and Francis Kohola, in addition to Kinzo Kaneko and the Sato family.3 The 1940 census recorded six performers, including the Sato family and Yoshitaro Hayashi. At this point, they occupied only 1.3% and 1.6% respectively of the Japanese population in Chicago.

How did the lives of Japanese performers who chose to stay and live in Chicago change? Did they have further opportunities to perform?

One incident illustrates the difficult and complicated lives of Japanese performers at this time. At a club in downtown Chicago, Isamu Ikehata, a performer from Kagoshima who had lived in New York for a few years, began arguing over money with Kiyo (aka Kyonosuke) Namba, one of Kumataro Namba’s sons from Kyoto and a member of the club. As the argument escalated, Charles Stone, an American performer, tried to mediate between the two; unfortunately, Ikehata slashed Stone with a knife and deeply injured his back. Consequently, Ikehata was arrested.4

Stone was such a fan of Japanese people, since he often performed with Japanese entertainers, that perhaps his attitude toward the accused Ikehata was a little too generous. In any event, Ikehata’s court procedure was postponed,5 and he was released on probation. Other local Japanese made sure that Stone did not lose any income due to his injuries and medical treatment.6

Six years later, Kiyo died in Chicago on August 13, 1934. He was thirty-seven years old. Another Japanese entertainer, Paul Naka, died in Chicago in December 1929. He had been born in Japan in 1897 and in July 1929, married an American woman from Chicago by the name of Helen, in Indiana. Only three months later, Helen became a widow and had to support herself as a housekeeper.7 Naka was only thirty-two years old at the time of his death.

Readers must be wondering whatever happened to Otome Tanaka and Yoshi Wakahama, the two children who became famous for having escaped from Namba in 1912. The name Otome appeared in the 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses, which means that she apparently settled down in Chicago during her teenage years.

This author assumes that K. Sato, one of the small children that “Mrs. Namba” brought from Japan in 1905, was Katsumi Sato, and that Yoshi Wakahama and Katsumi Sato were the same person. He may have borrowed the name of the Wakahama Troupe, for whom he was working, as his stage name when he ran away from Kumataro Namba with Otome. Following upon this assumption, the author presumes that Katsumi Sato eventually returned to live with Namba at 6348 Dante Avenue.

According to the World War I Registration, Sato was born in Fukushima in 1893 and was twenty-three years old and single when he was employed by Kumataro Namba in 1917.8 Otome and Katsumi Sato appear to have married at around this time.

According to the 1920 census, two families of performers lived at 6544 Blackstone Avenue in Chicago. One was the Hoshi family: Takichi, a vaudeville actor, his wife Yoshi, and their three-year-old daughter Soyo, who was born in Illinois. The other was the Sato family, the couple who had escaped Namba but remained in the entertainment business and eventually married: Katsumi, a vaudeville actor, his wife Otome, and their son, Kazuo, age three, who was also born in Illinois. With them lived more performers: Toku Totsuka, a twenty-eight-year-old single man and Toyo Kishi, a thirty-five-year-old single man. Katsumi Sato formed the Toyama Troupe and joined the Ringling Brothers Circus and the Cole Brothers Circus, touring North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana and Nevada.9

In the 1930 census ten years later, Katsumi and Otome Sato were reported to live at 6222 Dorchester Ave.10 The Satos had a total of five children born in the states that the Toyama troupe traveled to: Misato, their ten-year old daughter, was born in Kentucky, and Anna, eight years old, was born in Nebraska. Matsu and George, their six and four-year-old sons, were both born in Illinois like their eldest son, Kazuo.11

By the 1940 census, Katsumi Sato was forty-five years old and still listed as an actor. He managed to continue to find entertainment jobs through Thomas Burchill, a booking agent of the Western Vaudeville Managers’ Association.12 In 1940, the Sato family lived at 1343 North Wells Street and their children had also become performers, with the exception of their oldest daughter, Misato (also known as Geneva) and their youngest son, George. Misato was listed in the census as a waitress, and George, age thirteen, was presumably still too young to work.13

It is interesting to note that by this time, Denkichi Sato, who was probably Katsumi’s brother, had joined the Satos at 1343 N. Wells St.14 Denkichi Sato was born in July 1879 and was sixty-two years old when the war with Japan started in 1941.15 Since he had been performing in Chicago with the Tetsuwari troupe since World War I,16 we can also consider him a true Chicagoan Japanese.

Ikuta Fujita, also known as Jinkichi Fujita, was also well-known among local Japanese in Chicago. He had his own bicycle for acrobatic cycling and performed at casual meetings held by the Japanese. Fujita was invited to perform at a celebration party for the Japanese Emperor’s enthronement, held by the Japanese Association in 1928. At this party, Fujita performed cycling acrobatics alongside performances such as dancing, gitayu and naniwa-bushi singing, and shakuhachi and chikuzen biwa concertsby other local Japanese.17

Here is one colorful episode about Japanese acrobats in Chicago, a story that has three different versions, depending on whether it was told in Japanese communities in Chicago, New York, or San Francisco. As the story goes, in 1915, Tamaki Miura, the world-famous opera singer from Japan, made her debut in Chicago as “Cho-Cho San,” performing the title-role in Madame Butterfly with the Boston Pavlowa company at the Auditorium Theatre. It was the first time for a Chicago audience to see a Japanese woman play the role of a geisha on stage.18

Miura wanted a Japanese child to play the role of the deserted wife’s son in the opera, so she wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune looking for one. First came “a score of dainty, saffron Celestials, clad as gayly as a garden” from Chicago’s Chinatown,19 but Miura did not like any of them. When Miura exclaimed, “But I wanted a Japanese baby!” one of the older Chinese children left in a huff, exclaiming “I don’t want to be a Japanese child, either,” according to a Japanese newspaper in San Francisco.20 After a few days, a respectable-looking white woman brought Miura a three-year-old mixed-race boy. According to the woman, the boy’s name was Leon Iwamoto, “the son of Japanese tumblers and acrobats, who left him in my charge.”21 Miura delightedly accepted the boy.

One day at a rehearsal, most likely during the last scene of the opera, “death having stilled (Miura’s) voice, another was audible in the back of the theater, crying: Mama, mama, don’t cry! Please stop.” Boston Opera staff found the white woman hugging Leon to her breast, then she rose and started walking away rapidly. Asked “what in the world are you crying about,” the woman answered, “I am an American Mme. (Madame) Butterfly. I lied to you. This is my son. He is the son of a Japanese acrobat, who left me; I was only a girl.”22

While the Nichibei Shuho, published in New York, faithfully followed the Chicago Tribune article, (except that it added that the forlorn white mother had in fact married Iwamoto, but he had left her once the baby was born.)23 Shinsekai, the San Francisco publication, interestingly changed the white woman's identity to a Japanese woman and attributed these words to her: “I am now working at a photo shop. I often thought of committing suicide as Mme. Butterfly did. But I will not die leaving my child behind, alone. I never think of this as an honorable act.”24

Did turning the white woman into a Japanese woman represent the article author’s tiny but persistent resistance toward stereotypes of Japanese women and their tireless effort to break them down? Or was it because the Japanese on the West Coast, where interracial marriage was banned, could not believe that a white woman would have a relationship with a Japanese man who would leave her behind with a child? Or, was it because the Japanese were simply ashamed of how the Japanese acrobat, Iwamoto, treated a white woman?

We know that Leon Iwamoto was there for rehearsals, but we don't know whether he actually performed in front of an audience. In any event, according to the Chicago Tribune, “Tamaki Miura’s appearance was a triumph.”25

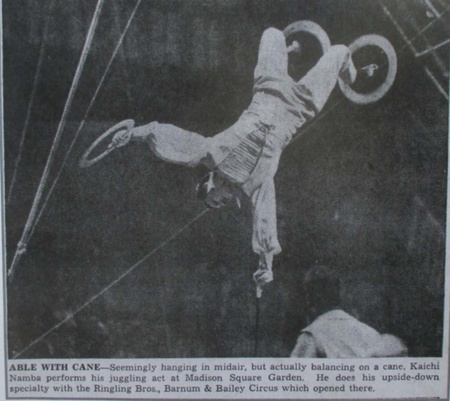

Finally, and incredibly, we note the persistence of the Namba troupe in American circus performances. Kaichi Namba was still one of the stars of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1958. He was already in his 60s, but twice daily still performed the “jump-up a flight of 12 steps on his head” in 195826 and his juggling and upside-down acrobatic specialties at Madison Square Garden in 1959.27

According to newspaper articles, Kaichi Namba had been in Australia at the outbreak of World War II. He was interned there and developed his head-jumping routine to entertain GIs in Australia. After he was repatriated to Japan and American occupation forces took over, he toured all of the American camps in Japan.28 It is possible that he found a way to return to the US through the American military. He is reported to have died in September 1979 but the location of his death is unknown, just as much of his life in Kyoto would never be known.

Notes:

1. Letter from Kuwajima to Uchida dated February 23, 1922, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 3-8-5-11-5.

2. Letter from Ohashi to Shidehara, dated August 17, 1926, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 3-8-5-11-5.

3. 1930 census.

4. Nichibei Jiho, June 30, 1928.

5. Nichibei Jiho, July 7, 1928.

6. Nichibei Jiho, July 21, 1928.

7. 1930 census.

8. World War I Registration.

9. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 251.

10. 1930 census.

11. Ibid.

12. World War II registration.

13. 1940 census.

14. World War II registration.

15. Ibid.

16. World War I registration.

17. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago ni Moyu, page 163; Nichibei Jiho November 17, 1928.

18. ChicagoTribune, October 7, 1915.

19. ChicagoTribune, October 1, 1915.

20. Shin Sekai, October 11, 1915.

21. ChicagoTribune, October 1, 1915.

22. Ibid.

23. Nichibei Shuho, October 9, 1915.

24. Shin Sekai, October, 11, 1915.

25. Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1915.

26. The Southern Democrat, July 17, 1958.

27. Bridgeport News, June 24, 1959.

28. The Southern Democrat, July 17, 1958, Oakland Tribune, Sept 25, 1958.

© 2022 Takako Day