As a second-generation Uchinānchu (Okinawan immigrant), Karen Tengan Okuda lives and works on the unceded lands of the Eora and Dharug peoples (Sydney, Australia). Okuda works as a Social Media Community Specialist for Special Broadcasting Service Australia.

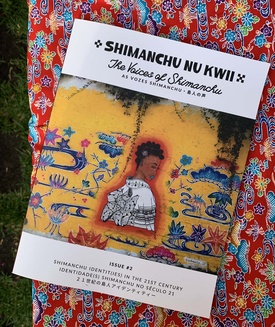

She is also a founding member and an editor of a magazine, Shimanchu Nu Kwii (meaning “voices of Shimanchu” in Uchināguchi).

“The magazine was born out of a desire to create a space where Shimanchu (island people) all over the world can connect with each other and share our stories,” said Okuda. Focusing on themes such as “Honoring Our Ancestors” and “Shimanchu Identit(ies) in the 21st Century,” the magazine publishes submissions from writers and artists from across the world, including the U.S., Australia, Brazil, and Okinawa. The first two issues, Summer 2021 and Winter 2022, are artfully crafted with a keen eye for print design and lushly produced with original photos and artwork.

Family Roots

“My parents are both from Uchinā (Okinawa) and came to Australia in 1995,” said Okuda. “My mother’s family is from Gushikawa, in the central part of the island, and she grew up in quite a traditional way. She’s from a big family that has passed down traditions and customs. She grew up speaking the indigenous language of Uchināguchi as well as Japanese.”

Describing her father’s family, she said, “My paternal grandmother is from Myāku (Miyako Island), and my paternal grandfather is from Amami, but he and his brothers grew up on Okinawa. Because both of my father’s parents were from outside of Okinawa, my father grew up speaking only Japanese and participated mostly in Okinawan traditions and customs, as opposed to Miyako or Amami customs.”

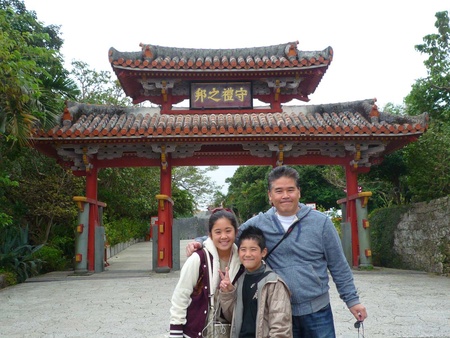

About her own upbringing, Okuda said, “I was born and raised on Eora and Dharug country, now known as Sydney, Australia. While I grew up in the Japanese community and with Japanese-Australian kids, I always knew my family was different. When we went back to see our family in Okinawa, it felt so different from Tokyo or Osaka. In Okinawa, the ocean was never too far away, the weather was different from Japan, and it just felt like no other place I’d ever been to.”

As Okuda grew older, she became interested in history and began to dig deeper into the history of the Ryukyu Kingdom (which later became Okinawa). She learned about the Ryukyu Annexation and assimilation policies, as well as the Battle of Okinawa and the subsequent occupation by the U.S.

“My interest in history triggered a deeper exploration of my heritage and identity,” she said. “Throughout high school and university, I would always ask my mother about how she grew up in Uchinā, the history of the islands, and her experiences in and out of Uchinā. Looking back she not only encouraged my love of history but was also a key figure in helping me understand where I come from.”

What does Nikkei mean to you? Do you identify as Nikkei?

Okuda defines Nikkei as “of Japanese descent,” with the kanji character 日(ni) representing Japan and 系 (kei) meaning lineage.

She does not identify as Nikkei herself. “I identify specifically as Uchinānchu/Okinawan to honor my ancestors, and also to signify that Japanese and Okinawan people are different. While we may have shared histories, Okinawan people (and Ryukyuan peoples as a whole) have our own distinct language, culture, and history that are not a subset of Japanese culture.”

She added, “I also prefer to identify more specifically as Uchinānchu/Okinawan, rather than using the broader term Nikkei, as there’s a plethora of experiences within the diaspora that’s often tied to place and the cultural context of that place. As an Okinawan I don’t want to speak for people from other Ryukyuan islands, who have their own distinct languages and cultures, and obviously growing up in so-called Australia has also helped shape me into who I am today.”

How do you identify as Okinawan?

“I identify as a diasporic Uchinānchu (Okinawan). While I am Uchinānchu and was brought up as Japanese and Okinawan for the most part, I also want to acknowledge that I didn’t grow up on Uchinā, so there are things that I may never understand or don’t know at this point in time. As a legacy of Japanese assimilation policies, there are also aspects of my culture that I’m reconnecting to as an adult, such as language and certain traditional customs.”

How have you participated in your Okinawan community?

“I grew up within my local Japanese-Australian community so when I was younger Okinawan culture was something that only existed at home—within stories, photos, and ornaments around the house. The mini shīsā that were on display in our entryway and the little kijimunā that sat peacefully next to them were daily reminders of where I came from. Also, the Japanese community here is quite small, and the Okinawan community here is even smaller, so there weren’t that many opportunities for me to get involved.”

Okuda has recently become more active within the local and broader diaspora Okinawan community. Before COVID-19 she traveled home to Uchinā at least once a year, but travel restrictions forced her to find other ways to be in touch with her culture. “I stumbled upon a Discord server for Ryukyuans, mostly in the diaspora,” she said. “This is where I was able to talk with other diaspora Ryukyuans for probably the first time in my life. I learned so much from the people on the server sharing information and stories. I learned about indigenous languages, traditions that had been dormant for decades due to colonialism, and Ryukyuan food. I also met other passionate and talented Ryukyuans who I joined to create what would eventually become our magazine, Shimanchu Nu Kwii.”

From the beginning, Shimanchu nu Kwii, purposefully carved out a creative space made by Ryukyuans, for Ryukyuans.

“We felt that there wasn’t an outlet for Ryukyuan people to share their own stories in their own space, as often it feels like we’re lumped in under the umbrella of Japan. I joined volunteers from the U.S. and Brazil to envision and create Shimanchu nu Kwii to showcase the talent and diversity within our community. We’ve worked hard to make it as multilingual as possible so it could be accessible to diaspora members around the world. There’s writing, art, photography, music, and so much more included in the magazine. At the moment we’re aiming to publish bi-annually, but we’re also a volunteer-run project that is a labor of love so time can sometimes be a great enemy to us. Working as an editor on this project has been such a blessing as I’ve been able to connect and learn from Ryukyuans across the globe. Seeing everyone’s works has been very moving and makes me beam with pride as a Ryukyuan!”

Another way Okuda participates in Okinawan culture is through dance. She recently started dancing eisā, an Okinawan folk dance, in Sydney. “We’re a small team that performs mainly at local community events.

While it’s not the same experience as it would be back in Uchinā, as we obviously don’t have dances unique to this area (back in Uchinā each village has its own unique eisā dance style) or have events where eisā is traditionally danced, it’s been a very fulfilling experience. Especially as someone who grew up dancing, feeling the music and the drums throughout my body is something that I love so much! Also, both of my parents were in seinen-kai (young person’s association) and danced eisā when they were young so it’s also lovely to be able to experience a version of that myself.”

How have Australian history and culture impacted your identity?

“I don’t identify with the ‘true blue’ Aussie or what the media represents to be ‘Australian’ as more often than not, being a ‘true blue Aussie’ is based in racist colonial ideals. Interestingly enough, it’s when I’m away from Sydney that I see how being born and raised in Sydney has shaped who I am today. I become more conscious of the social contexts in which I’ve grown up. I grew up in areas that were quite multicultural and attended schools with all kinds of kids. As a settler on these lands and as a diasporic Indigenous person, I’ve also learned a lot from the First Nations peoples here. I feel privileged to have grown up the way I did and learn from people of such diverse backgrounds.”

© 2022 Karen Kawaguchi