Japanese Immigrant Communities in the Era of Globalization

The waves of immigration during the last third of the 20th century and the first two decades of the present century were driven by an intense exchange between Japan and Mexico in the areas of business and education.

As mentioned, Japanese investment was the great driver of the flow of migrants during that period. It is also important to note that Japanese cultural industries began to develop a strong presence overseas through television programs and cartoons (now known as anime, or アニメ). One series in particular, “Princess Comet,” which aired in the 1970s, influenced an entire generation of TV viewers in Mexico and provided a glimpse into the reality of the Japanese middle class through the adventures of a young woman who comes from another planet to watch over mischievous children.

With respect to direct Japanese investment in Mexico, the Japan-Mexico Economic Partnership Agreement, signed in 2004, increased the flow of people in both directions. In 2021, there were more than 11,000 Japanese immigrants, mostly living in central Mexico, where many work for large Japanese auto companies and related service and supply companies.

In addition, the two countries signed the Japan-Mexico Trainee and Student Exchange Program in 1971, which boosted university enrollment of students of both nationalities. Likewise, the study and research centers focusing on the cultures of both countries grew, and in 1976, the Nobel Prize-winning Japanese author Kenzaburo Oe was a visiting professor at the College of Mexico.

Among the students and artists who came to Mexico was archaeologist Yoko Sugiura, painters Kishio Murata and Midori Suzuki, and sculptor Kiyoto Ota. These migrants not only came to study, but eventually found spaces in Mexico that enabled them to deepen and develop what they learned. There may be several reasons why they have decided to remain in Mexico, and although they have not become Mexican citizens, they feel that they are integrated into the country’s culture. Perhaps there is something special about Mexico that convinces you to stay.

Another immigrant who has stayed in Mexico is violinist Rie Watanabe. She was very young when she arrived in 1986 to study with renowned violinist Yuriko Kuronuma, who had become internationally known. Kuronuma lived for many years in Mexico and wrote a book, Letter from Mexico, that is still available today in Japan. Also during that decade she founded an academy in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City where many children and young adults receive training. Since that time, Watanabe has been in Mexico and currently lives in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. She is an active participant in various music schools for indigenous people in Chiapas and Oaxaca where children and young people receive musical training, playing in bands that are an essential part of musical culture and festivals in their respective towns.

Another notable immigrant is Shozo Ogino. A graduate of Waseda University, he arrived in Mexico in 1970 and for the first few years, taught Japanese language classes. Later he took charge of Shukan Nichiboku, a weeklynewspaper reporting on news and activities in the Japanese community. In addition to journalism, Ogino researched the lives and circumstances of Japanese immigrants throughout Mexico, acquiring in-depth knowledge of the country they became part of. Using this large body of knowledge, he published Five Centuries Crossing the Ocean (Cinco centurias a través del mar), a book whose more than 500 pages detail immigrant stories, illustrated with hundreds of photographs. Ogino is the official historian of Japanese immigration to Mexico, but with the knowledge he has collected, he is also a recognized scholar of Mexican history.

Immigrants have also made contributions to promotion of Japanese culinary culture in Mexico. Several Japanese restaurants started up in Mexico in the 1970s, including Daruma, Daikoku, Harumi, Miyako, Taro, Nagaoka and Samurai in Mexico City and elsewhere, attracting Mexican diners. This was before the major boom in Japanese food, so words like sushi and yakemeshi were still largely unknown. The rising popularity of Japanese food in recent decades means that they are now familiar words throughout Mexico, but also they prepared in a unique way. Sushi in Mexico often contains avocado or fruit and the spicy condiments found commonly in Mexican cuisine are used to prepare Japanese dishes in ways that traditional cooks could hardly have imagined.

Another notable aspect is that new generations, the descendants of the first waves of Japanese immigrants, participate in daily life in Mexico in ways that are very different from their ancestors. Many of these young people, including graduates of the Japanese-Mexican School and other institutions, do not always have in-depth knowledge of the lives of the pioneers in Mexico and the significant challenges they faced so that young people now can earn university degrees. They have access to a variety of professions and specializations that are very different from those of their parents, and they do not necessarily follow the needs of the family businesses founded by their ancestors. Electrical engineering, architecture, biology, art, and marketing are just some of the diverse degrees they obtain, in addition to opportunities for graduate study in Mexico and abroad.

From the newest generations, I’ll mention just a few examples to illustrate their interests and activities. Yukari Hirasawa is a university graduate but also studied Japanese music for many years and plays the koto. Akiko Iida studied at the prestigious Takarazuka art school in Japan and since returning to Mexico, has performed as an actress, dancer, singer, and director, producing plays and other performances that innovatively and creatively combine her knowledge of both cultures. Her artistic activity is hugely varied, as she has acted in a production of the classic Mexican film “The Gray Car” and staged her own plays and musicals with classic Japanese themes.

For his part, Saburo Iida, who has a degree in electronic engineering, is now an innovative musician of contemporary rhythms, fusions and compositions with influences from various countries. In these three cases, the music and theater they have produced are evidence of how the mixture of different pathways has enriched their artistic expression. The freeform and heterodox ways in which the koto is played and the integrating of Japanese sounds and dance enables them to put their own mark on the classic Japanese canon.

Not just these artists, but also thousands of Mexican Nikkei youth in other fields are part of the cultural and professional traditions in which they have been raised and educated. The cultural dimension of their social life is created and recreated like the sushi seasoned with chipotle sauce, which has become such a popular element of the palate of Mexican consumers. This cultural dimension is also the product of the history of Japanese immigration to Mexico to which they belong, a transnational history that has also become deeply rooted over the past 125 years.

Photographer Seiji Shinohara, who moved to Mexico in 1976, has visually documented three generations of Japanese immigrants living throughout Mexico. His photos were published in a series of books; one of them, called Rice and Tortilla (La Arrotilla), includes images of bicultural couples where one person is from Japan and the other is from Mexico (as is his own case). Shinohara’s beautiful photos reveal the elements that these immigrants and descendants of the civilizations of rice and corn interweave in their daily lives.

Like other immigrants whose interest in Mexico started with their attraction to the civilizations of corn that flourished before the Spanish conquest, Shinji Hirai, a graduate of Keio University, made his first trip to Mexico in 1994. During that trip he visited numerous archaeological sites and later enrolled at the Autonomous Metropolitan University to study anthropology, earning a master’s degree and a PhD. He is now a research professor at the Center for Research and Higher Education in Anthropology in Monterrey. In addition to his academic work for that leading institution, he was motivated by the descendants of Japanese immigrants living in that region to found the Raices (Roots) program. This community program supports research and preservation of the history of Japanese migration and incentivizes Japanese descendants to make it their own. In fact, Hirai himself is fascinated with the stories of the Japanese immigrants who worked in that arid region. By participating in and being rooted in both cultures, his own process of self-identification has taken on a new perspective, under novel circumstances, just like those who arrived in Mexico more than a century ago.

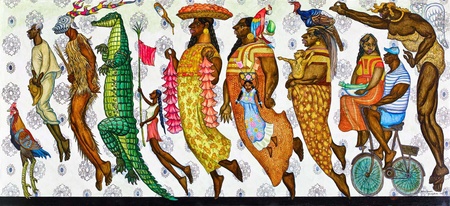

“This is where my spirit was born and has grown,” says the painter Shinzaburo Takeda, who has lived in Mexico since 1963 and in Oaxaca since 1978. Mexico has allowed him to discover himself and become a Japanese-Oaxacan in the process. But Takeda also believes that his “heart is a red isthmic color”, referring to the identity that Oaxacan culture has given to him.

If we follow Takeda’s heart, we would find that the unique colors and aromas of Nikkei identity and spirit (as generic and homogenizing as those terms are) depend on the roots and circumstances through which the integration of immigrants has developed. The “Niquei” spirit and identity with a “q” are nourished by specific, lived historic content, arising from the cultural diversity of Mexico in which Japanese immigration has taken root in the various regions of the country.

The hard work, dedication and history of these “Niquei” immigrants and their descendants are the body and soul of relations between Mexico and Japan. Without these immigrants, Mexico’s relationship with Japan and Japanese investment, both so important in recent decades, would be just like luxurious armor, hollow and lacking in substance.

© 2022 Sergio Hernández Galindo