In November 2020, I published an article for Discover Nikkei addressing The New Yorker’s coverage of the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans. Although the magazine’s wartime issues provided scant coverage of the incarceration, mostly couched in vague allusions to the topic, such brief mentions nonetheless indicate the subtle buildup of consciousness of the issue among both contributors and readers. It also indicates The New Yorker’s overall movement from a purely humor magazine to one engaged in serious discussion of culture and politics. To be sure, The New Yorker was hardly unique in its bare coverage of wartime incarceration.

Among mainstream periodicals, the nature and frequency of reports on the subject varied widely: some mainstream periodicals, such as The Atlantic, rarely mentioned it, LIFE magazine offered more extensive coverage of the initial removal and of the situation in camps like Tule Lake, and Harper’s published important articles by Kenneth Ringle and Eugene Rostow supporting Japanese Americans. The mainstream periodical that stands out among American media in the quality and diversity of its reportage on the wartime experience of Japanese Americans is The New Republic.

For most of the 20th century, The New Republic was considered a leading soundboard for liberal opinion. Founded in 1914 by Walter Lippmann, Herbert Croly, and Walter Weyl as a magazine for the Progressive movement, the magazine boasted a substantial readership among political and literary figures and featured a wide range of noted contributors. From 1930 to 1946, under the editorship of Bruce Bliven, The New Republic published pieces by future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, historian Charles Beard, and authors John Dos Passos and George Orwell, among others.

It was during Bliven’s tenure as editor that The New Republic turned to examine political and social issues wrought by the U.S. entry into World War II, with the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast being one of them. And even before the question of forced removal arose, The New Republic began to question the logic of wartime hysteria. In a column from January 1942 on the infamous Tanaka Memorial, a sensational document cited by anti-Japanese activists as evidence of a mass conspiracy among Japanese to conquer the world, The New Republic editorialized that the document was false and insignificant.

Two months later, in March 1942, The New Republic began publishing articles directly commenting on Japanese Americans. A substantial number of these articles were written by journalist and social activist Carey McWilliams, who was then a California state employee. Around the same time as he testified before the Tolan Committee about the consequences of forced removal for Japanese Americans, McWilliams issued an initial evaluation of the situation, which was printed in the magazine’s March 2, 1942, issue.

In the article, McWilliams accepted some of the baseless claims about Japanese Americans put forth by proponents of mass removal. For example, he stated that the wholesale expulsion of the Japanese American community at Terminal Island by Naval authorities the previous week was justifiable based on the “potential” for espionage. He also noted that the Japanese American community was already suffering, citing instances of violence, and rising unemployment rates. In his conclusion, he opposed mass imprisonment of the community, though he highlighted the agricultural demands of the war and the importance of Japanese American farmers rather than questions of justice and constitutional rights. Rather, he recommended following the guidance of Attorney General Francis Biddle and called for selective arrests.

On April 6, 1942, in the wake of the initial forced removal of Japanese Americans to Army detention centers, McWilliams penned a second article. McWilliams praised the Tolan Committee for raising awareness of the crisis of forced removal as described in its reports, and deplored the inaction of West Coast politicians. Conversely, McWilliams criticized the committee’s inequal treatment of Japanese Americans in comparison to German and Italian aliens and their acceptance of racial difference as a legitimate argument for disparate treatment. McWilliams closed by arguing that “there is no single domestic issue at the moment of greater importance than the formulation of a policy on “enemy aliens” consistent with our war aims.”

In September 1942, The New Republic’s editorial staff proceeded to publish two articles on the subject. In the first article, the staff applauded the War Relocation Authority for its overall handling of the camps and the leadership of the Nisei in organizing communal self-governance within their borders. In contrast, the second article, titled “An American Nuremberg Law,” deplored the actions of the Senate Committee on Immigration in proposing a bill, S. 2293.

The bill, proposed by Senator Tom Stewart of Tennessee, would grant the Secretary of War the power to incarcerate Japanese Americans for the duration of the war without due process, and pave the way for deportation afterwards. The bill, according to the article, assumed that Japanese Americans were Japanese subjects and would violate the ruling of Wong Kim Ark vs. United States that upheld birthright citizenship. Ironically, in describing the bill, the editorial board missed the chance to comment on the confinement and lack of due process present in the ongoing incarceration.

On September 12, 1942, The New Republic published a piece by University of Hawaii professor Blake Clark, refuting rumors about fifth column activity among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. In the article, Professor Clark countered widespread rumors that Japanese Americans had blocked the roads of Honolulu during the bombing of Pearl Harbor, that a Japanese American was among the pilots of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and that a Japanese American family had helped a downed Japanese pilot. Rather, Clark told his readers that Japanese Americans formed part of the Hawaiian National Guard at the time of the attack, and that Japanese community leaders had participated in civil defense units during the attack.

The article’s appearance in September 1942 did not touch directly on incarceration. However, it represents a surprising example of a publication refuting the false reports of fifth column activity in Hawaii that had been disseminated by Navy Secretary Frank Knox and mainstream press outlets at the time.

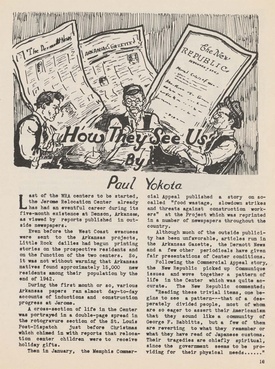

Throughout 1943, The New Republic published regular reports on the camps. In January 1943, the editors published an anonymous article on the Jerome Concentration Camp in Denson, Arkansas. The story, which was likely ghostwritten by Nisei editor Eddie Shimano, refuted widespread rumors of sabotage at the camp, and instead showed that community members held democratic elections, played football, and published a community paper titled The Denson Communique (later named The Denson Tribune). Likewise, the article reported on two incidents of racial violence occurred where locals shot at Japanese Americans, with one of the victims a nisei soldier visiting the camp.

Later in the year, the editors of The New Republic commented negatively on remarks by Congressman Martin Dies, the head of the House Un-American Activities Committee. In addition to deriding the sensational comments of the Dies Committee on the 1943 Detroit uprising, the editors also criticized the Committee’s zealous investigations of “coddling” in the War Relocation Authority camps, noting that the Japanese government had threatened reprisals against American prisoners of war over mistreatment of Japanese in America. During this period, the editorial staff regularly defended the work of the War Relocation Authority and its director, Dillon Myer, against the attacks of the Dies Committee and the Senate’s Costello Committee, noting in particular the Costello Committee’s support of West Coast racists.

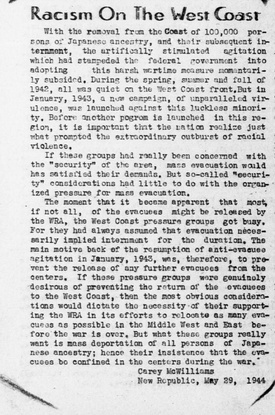

In its issues for May 29 and June 12, 1944, The New Republic published “Racism on the West Coast,” a new two-part essay by Carey McWilliams on the issue of the incarceration. In the article, McWilliams (who no longer was a California state employee and could thereby speak more openly) indicted West Coast politicians and the media for intentionally inciting racial hatred against Japanese Americans. McWilliams particularly lambasted the work of Congress’s Dies Committee, the California State Assembly’s Joint Immigration Committee (AKA the Tenney Committee) and the State Assembly’s Gannon Committee for promoting white supremacy and allowing racial hysteria to influence the government’s decision to incarcerate the West Coast Japanese community. Both articles foreshadowed the arguments made in McWilliams’s 1944 landmark book, Prejudice.

In June 1945, War Relocation Authority director Dillon Myer wrote “The WRA Says ‘Thirty’,” the last article on the camps to appear in The New Republic during the War years. In it, Myer laid out the final plans for the War Relocation Authority for an eventual closure of the camps. Myer praised the work of his agency in handling the camps, but argued that their place in American society was necessarily temporarily. As the camps closed, Japanese American families would return to the West Coast, Myer argued, and would become a part of society as before. In foreshadowing his later work as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Myer argued that the immediate closure of the camps was needed for Japanese Americans to stand independently – a policy later reflected in his infamous ‘termination’ policy for Native American reservations.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen