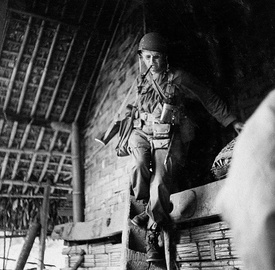

Far from the battlefields of Europe and Africa, another war was brewing in 1943 in the thick, remote jungles of the China-Burma-India Theater.

As enemy forces expanded their reach in the region, President Franklin Roosevelt issued a call for volunteers to take part in a top-secret and highly dangerous mission.

Nearly 3,000 soldiers answered. They didn’t know where they were going or what their mission would entail. The volunteers were considered “expendable,” as the casualty rate was expected to be high.

They were needed to destroy supply lines and communications behind enemy lines and capture the Myitkyina airfield in Japanese-held Burma.

The operation took less than a year. In just five months, the unit—now famously known as Merrill’s Marauders after its commander, Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill—marched 1,000 miles over dangerous terrain, fought in five major battles and engaged the Japanese 30 times.

Despite being severely outnumbered by Japan’s elite 18th Division, the Marauders secured victory for the U.S.

Now, they’re fighting to receive recognition for their efforts more than seven decades after beating the odds to accomplish their mission.

Planning and Preparation

Two years before the Marauders arrived in Burma, the country that’s now known as Myanmar had been almost overtaken by Japanese forces. According to the U.S. Army, their dominance in the China-Burma-India Theater threatened communications between the U.S. and Australasia.

In 1943, the Allies went on the offensive as British Brig. Gen. Orde Wingate, British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten and U.S. Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell executed major, long-range offensive operations in the theater.

Merrill’s Marauders, formally known as the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), were to support Stilwell’s offensive to conquer northern Burma.

The unit, code named “Galahad,” was created after Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met at the Quebec Conference in August 1943.

After Roosevelt’s call for “jungle fighters,” hundreds of soldiers from the Army’s ground forces made their way to Camp Stoneman in California—a major staging area and jumping-off point for more than 1 million soldiers heading to the Pacific Theater during World War II.

“Through these portals pass the best damn soldiers in the world,” read a sign inscribed on the camp’s entrance.

Soldiers came from stateside units, as well as units with experience in Panama and Trinidad, where they served in the campaigns of Guadalcanal, New Guinea and New Georgia.

The unit consisted of 14 Nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans, from Hawaii and the continental U.S who served as interpreters and translators. All of them volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service—some from internment camps—and, again, all later volunteered for Roosevelt’s top-secret mission.

After initial training at Camp Stoneman, the soldiers boarded the ocean liner Lurline, a former luxury cruise ship that had been turned into a troop transport, and shipped out on Sept. 21, 1943.

‘Country, Duty, Honor’

Gilbert Howland joined the Army shortly after his 18th birthday. He served in the Panama region, where he trained with heavy weapons, before moving with his unit to Trinidad after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

While on his way home with other soldiers for a 15-day leave, Howland learned about the president’s request during a stop in Puerto Rico.

“A colonel came down from Washington, D.C., and said that President Roosevelt had come out for a request for 3,000 jungle fighters,” said Howland, now 96. “When the colonel said you’d be going on a mission, he didn’t say where, he didn’t say if it was dangerous or anything.”

Howland was among 124 men who immediately volunteered.

“Country, Duty, Honor,” Howland said. “That’s my motto.”

In October 1943, Robert Passanisi lined up alongside his fellow soldiers of the 76th Signal Company to listen to the call for volunteers.

Signalmen volunteers, preferably radio repairmen, were needed for “a dangerous mission of three months and three months of training, with an expected casualty rate of more than 85%,” said Passanisi, now 95 and the Merrill’s Marauders Association’s historian.

“I was in the Army like 18 months, and I had two brothers that had less time in the Army than I did and were already in Europe,” he said. “I may have felt guilty for I didn’t feel I was doing my part.”

Passanisi stepped forward to volunteer. He was the only soldier out of 250 men in his company to do so.

“I could hear the whispers in back of me [saying], ‘What, are you crazy?’ ” Passanisi said.

1,000-Mile Journey

The Lurline headed to New Caledonia, where it picked up several hundred battle-tested soldiers from South Pacific Command and continued south and around Australia. The ship reached its final stop, Bombay, on Oct. 31, 1943.

After disembarking in Bombay, now known as Mumbai, the unit began secretly training in the jungles of Central India alongside Air Corps and Signal Corps personnel, mules and mule drivers.

The 5307th was made up of six combat teams color-coded Red, White, Blue, Green, Orange and Khaki. Each of the unit’s three battalions consisted of two combat teams.

Between November 1943 and February 1944, the soldiers underwent intense training that included small-unit attacks, navigation, river crossing, scouting, patrolling and weapons.

In February, the Marauders began their 1,000-mile trek to Myitkyina.

“Merrill said there will be no riding, we’re going to walk it,” Howland said. “It was 110 miles of Ledo Road that was being built at that time to connect onto the Burma Road so they could get supplies into China by trucks.”

The walk took about 10 days, Howland said, and when they arrived, Stilwell was waiting.

“He gave us a good talk,” he said.

The unit continued its journey through the Himalayan Mountains, bush, water and thick jungle. The soldiers only had equipment and supplies—including mortars, ammunition, heavy long- and short-range radios, and bazookas—that they could carry on their backs or on mules.

“It was all very high ground,” Howland said. “The mules would fall off the cliffs, and they’d have to go down and get the ammunition and what was down there and the mules and get them back up on the trails.”

The Marauders fought against enemy forces, tropical diseases, hunger, exhaustion and treacherous terrain along the way.

The unit’s five major battles against the Imperial Japanese Army included Walawbum, Shaduzup, Inkangahtwang, Nhpum Ga and Myitkyina, where the only all-weather airstrip in Burma was located.

“We knew what we were doing because we were well trained,” Howland said.

The Nisei were instrumental in helping the American troops stay a step ahead of the Japanese forces in the area. They would sneak up on the Japanese and listen to their conversations, Howland said, then share what they heard with the rest of the unit.

“They tapped in on the phone line and found out all the good information,” Howland said. “The Japanese were crying for reinforcements because we were hitting pretty hard on their tails.”

The Burmese natives turned against the Japanese, he said, and came over to the Allies.

“Believe me, that helped us a lot,” Howland said. “Knowing what trails to take, where the Japanese were, what they were doing, and they even fought themselves.”

Because of the thick, and almost impenetrable, jungle terrain, the soldiers had to make clearings for resupply air drops and evacuations. Wounded Marauders were carried on a makeshift stretcher until an evacuation was possible—usually in a small village where Marauders would hack out a landing strip for a small plane—and flown out one at a time.

By August 1944, the unit accomplished its mission, not only disrupting enemy supply and communication lines but also taking the town of Myitkyina and the airstrip. By freeing Burma’s airspace, the successful mission enabled supplies to be flown in and created a critical Allied land route into China.

Just over 100 Marauders were left in fighting shape—and only two uninjured or not ill—by the time the unit disbanded in 1944, according to The Associated Press. The unit had lost more than 1,000 soldiers to injuries and disease.

“Enduring the humanly unendurable is really possible when the price is right,” Passanisi said.

Howland and Passanisi, along with hundreds of others, came down with malaria or other tropical diseases. Howland, who went on to serve in the Korean War and the Vietnam War, was also wounded by shrapnel during the fight in Nhpum Ga.

The unit was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, and every Marauder received the Bronze Star.

Legacy Continues

While the Marauders’ mission concluded in a few months, their legacy has continued almost 76 years later. Today, fewer than 10 of them are still living.

“It is important to remember the many sacrifices that were made and the lives that were cut short so that our future generations would be able to enjoy their God-given freedom, and to remember that their freedom was won at a high price,” Passanisi said.

While some Marauders received additional honors for their wartime efforts, the Association of the U.S. Army is working with lawmakers, surviving Marauders and their descendants to gain support for recognition under the Congressional Gold Medal Act—legislation that aims to bestow the honor on the entire unit.

“You have an honor to your men, to your troops,” said Howland, who received three Combat Infantryman Badges during his almost 30-year Army career.

Passanisi and Howland, both Ranger Hall of Fame inductees, members of Congress and AUSA representatives met on Capitol Hill earlier this year to garner support for the legislation. The event concluded with a reception in the veterans’ honor.

“I feel like it’s going to happen. I just hope it happens sooner rather than later,” said Jonnie Clasen, daughter of the late Merrill’s Marauder Master Sgt. Vincent Melillo. “They deserve this. They were one of the most unrewarded units.”

No other combat force during World War II, except for the 1st Marine Division, faced as much uninterrupted jungle fighting as Merrill’s Marauders.

“I’ll tell you, the boys I had, they fought like tigers when they had to,” Howland said. “No backing down.”

* * * * *

Legacy of Proud Service

When the U.S. entered World War II, it needed an understanding of Japanese language and culture for American intelligence efforts to succeed.

The War Department turned to second-generation Japanese Americans, or Nisei, who used their language skills to help win the war against Japan.

About 5,000 Nisei had been drafted or volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army after the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940 was enacted, the first peacetime draft in U.S. history initially targeted at 18- to 35-year-old males. According to the Army, draft notices were sent to the homes of 284,000 Japanese immigrants and their families on the West Coast and in the Territory of Hawaii—and the communities “responded with pride.”

After the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, many Japanese who had entered the military were discharged or reassigned, and those not yet drafted were reclassified as aliens not acceptable for military service. Many Japanese Americans were accused, without evidence, of spying for Japan and, despite their willingness to serve, their loyalty was questioned. Over 300 members of the month-old Hawaii Territorial Guard, made up of ROTC cadets and volunteers, were discharged as a result of this order.

On Feb. 12, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order that put more than 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps for the remainder of the war, but in the spring of 1943 the Army started looking for Japanese American volunteers to be part of combat units. Army teams were sent into internment camps to screen draft-age men for possible service.

The result was the formation of Nisei-only units and the acceptance of 14 Nisei into the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional)—now known as Merrill’s Marauders—to serve a crucial role as interpreters.

Led by 1st Lt. William Laffin, Japanese-born and raised, and by Sgt. Edward Mitsukado, a court reporter from Hawaii, the Marauder’s Nisei were assigned two-each to combat teams and two to headquarters. All 14 survived and received Combat Infantryman Badges.

Of the estimated 33,000 Japanese Americans who served during World War II, roughly 6,000 served in the Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific and China-Burma-India Theaters.

*From ARMY magazine, April 2020, Vol. 70, No. 4. Copyright 2020 by the Association of the U.S. Army, all rights reserved. Reproduced by permission.

© 2020 Association of the U.S. Army