When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, President Trump was quick to call this virus the “Chinese virus” or “kung-flu”. The use of these terms in widespread media conditioned many to believe that all Asians are to blame for the pandemic. Due to this racist rhetoric, Asians, along with Asian Americans, have experienced a sharp increase in hate incidents; more than reported in the past few years. In fact, over 6,600 hate incidents were reported from the organization, Stop AAPI Hate, from March 2020 to March 2021.1 Although this anti-Asian hate is currently on the rise, this problem began hundreds of years ago when Asians first began immigrating to America.

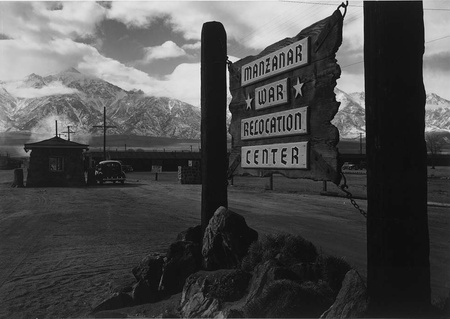

Asians began immigrating to the United States in the 1800s in hopes of a better, happier, and more successful life. The Chinese were one of the first of the Asian groups to arrive in America in 1849. Following the Chinese immigration was a period of time when many Japanese began to immigrate to the United States where they unfortunately experienced an abundance of racism and discrimination. According to the Manzanar National Historic Site, examples of such discrimination included “anti-Japanese organizations, such as the Asiatic Exclusion League, attempts at school segregation (which eventually affected Nisei—second generation Japanese—under the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’), and a growing number of violent attacks on individuals and businesses”.2 To make matters worse, in 1942, during World War II, President Roosevelt passed Executive Order 9066 which forced thousands of Japanese American citizens into incarceration camps, such as Manzanar.3

As terrifying as this was, the government was quick to label this action of forcing innocent people into camps solely based upon their heritage as a form of “relocation” and “evacuation”. This terminology implies positive connotations about a horrific incident that can strongly influence the way people think about these historical events. The terms “relocation” and “evacuation” are words that one would typically use in order to describe the process the government takes to move people out of their homes in order to help them escape a dangerous threat, such as a forest fire. In fact, one of Merriam Webster’s definitions for “evacuate” is, “to withdraw from a place in an organized way especially for protection”.4 Forcing thousands of people of Japanese descent out of their homes purely due to their heritage is not for protection or for the sake of their well-being and safety. These terms are still being used today in order to describe the atrocities that happened to the Japanese Americans during World War II, which can make these horrific events seem less terrifying and unjust than they actually were.

I recently had the privilege of speaking with Ms. Janet Watanabe, a close friend of my grandma’s. Ms. Watanabe grew up in Lancaster, CA, before she was forced into Poston incarceration camp in Arizona when she was finishing the 4th grade. She explained how camp life was very intimidating at first, especially because there were soldiers carrying bayonets around the camp. However, it was her return to school after her almost four years in camp where she really felt her self-esteem drop. After returning to school in the 8th grade, she explained that she had never felt more alone. The fact that no one, not even her friends, had asked her about her experience in camp, apologized for the fact that she was forced to be there for several years, or wondered how she was doing after camp, really saddened Ms. Watanabe. She states, “I wanted to know how they felt about it and wanted them to know how I felt too. We didn’t do anything bad. We were still fighting for our country. We weren’t bad people.”

The lack of words from her classmates, friends, teachers, and acquaintances evidently showed their lack of sympathy for all of the horrific things that had happened to these innocent Japanese Americans during World War II. Although we are not witnessing a repeat of this horrific history of incarceration camps, the strength of both words and the lack thereof when it comes to discrimination, has yet to come to an end.

In this recent spike in violent hate crimes toward Asians and Asian Americans in the past year, many, including myself, have been very fearful for our own safety in our neighborhoods. I used to live in a city that is known to be a rather safe neighborhood home to many families. On June 12th, I received word of a racist attack at a park where I often go to for lunch and picnics with friends.

A young Asian woman was exercising on the steps at Wilson Park when an older lady approached her and began yelling things such as, “Get the (expletive) out of this state. Go back to whatever Asian country you belong in,” and, "You (expletive). This is not your place, this is not your home. We do not want you here. Put that on Facebook. I hope you do. Because every (expletive) person will beat the (expletive) out of you from here on out.”5

Growing up in a typically safe area, this truly terrified me. After many more hate crimes being published on social media and the growing fetish for Asian women, I began to grow even more fearful. These words really stuck with me. I have always felt like I have been accepted for who I am and have never experienced any explicit type of racism. Just imagining a stranger yelling at me with all of the hate in their heart, telling me to leave the place I have called home for my entire life was not only terrifying, but also heartbreaking. This fear based upon one’s heritage should not exist within anyone.

Unfortunately, this racism can also be seen within today’s education systems affecting children. Matthew Saito, a current student at Loyola Marymount University, shares his story of the verbal racism he encountered during high school. Matthew Saito attended a primarily Caucasian high school where he was one of the only Asian Americans on his high school basketball team. He states that some of his teammates would nickname him “ni-hao”, mock Asian languages, and laugh at Asian slurs and racism.

At the time, Saito did not feel hurt by this casual racism, as they all brushed it off and didn’t take it too seriously. However, looking back at these incidents, Saito wishes that he had told his teammates that this casual racism was unacceptable. Although it did not negatively affect him personally at the time, in retrospect, he acknowledges that by letting his teammates constantly engage in these racial slurs and actions, they may continue to do so to others without knowing how harmful these words can be. He mentions, “Maybe I should’ve said something because if I don’t say something it kind of perpetuates their thinking.” Saito states that his former teammates could still be unknowingly harming others with this rhetoric.

Hence, we must teach the youth that even racial slurs that they do not intend to cause harm, can actually hurt those around them. This “casual” verbal racism is not acceptable, and we must educate people on this matter.

Despite all of this discrimination and lack of emphasis on how racial slurs can hurt others, law enforcement is having a difficult time defining crimes as racially motivated. Many are outraged at the government because of the rising racism toward Asians and how only a small amount of violent crimes against innocent Asian Americans are being handled as hate crimes. According to the New York Times, experts state that “proving a racist motive can be particularly difficult with attacks against Asians,” especially because “there is no widely recognized symbol of anti-Asian hate comparable to a noose or a swastika.”6

Additionally, prosecutors must provide solid evidence of a racially based motive for the crime, otherwise the defendant cannot be charged with a hate crime.7 For example, Xiao Zhen Xie, a 75 year-old Asian American was unexpectedly beaten by a man who attacked her unprovoked.8 However, articles have been published fighting against defining this incident as a hate crime against Asians due to a lack of evidence on the perpetrator’s motive.9 Without the defendant calling an Asian or Asian American negative slurs or verbally being racist, it can be difficult to deem their criminal actions as racially motivated, which many find frustrating.

Although much of this article has been focusing on the connotations and negative effects that words can have on individuals as well as our community, this fight for justice and equality has truly brought people together. On March 19, 2020, the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council (A3PCON), Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA), and the Asian American Studies Department of San Francisco State University created the “Stop AAPI Hate” coalition.10 According to their website, the coalition “tracks and responds to incidents of hate, violence, harassment, discrimination, shunning, and child bullying against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.”11 On their website, one is also able to report any anti-Asian hate crime they have experienced. Many have found comfort in hearing the words of others who have gone through similar experiences as them. According to Helen Hsu, a psychologist at Stanford University, communal healing and the feeling that others are there to support you can be very healing, similar to therapy.12

Hence, reading the words and supportive statements of others going through the same thing as you can be extremely beneficial. This verbal or written support is something that my grandma’s friend, Janet Watanabe, unfortunately lacked when she returned from camp which led to her feeling more alone than she ever had before. For me personally, this past year has been the toughest one for me yet. I would not have made it through without the support and love from my friends, and especially my family. The kind words that they use to encourage me every day to stay strong and keep moving forward are ones that I hold close to my heart.

Knowing that anti-Asian racism dates back to hundreds of years ago and has persisted through generations to this day, we must fight hard to combat this issue. We need to stop the hateful words that people are speaking to one another and begin sharing more of our stories to strengthen our community. Hopefully, with the growing support Asian Americans are experiencing during this time and the higher amount of self-reports of Asian hate crimes, we will begin to see both positive and drastic changes in our world.

Notes:

1. Russell Jeung, et al. “National Report,” Stop AAPI Hate, 20 May 2021.

2. “A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II,” National Parks Service.

3. “Document for February 19th: Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese,” National Archives and Records Administration.

4.“evacuate,” Merriam-Webster.

5. “VIDEO: Racist Rant Launched at Asian Woman Exercising in Southern California Park,” ABC7 News, 11 June 2020.

6. Nicole Hong and Jonah E. Bromwich, “Asian-Americans Are Being Attacked. Why Are Hate Crime Charges So Rare?” The New York Times, 18 Mar. 2021.

7. Ibid.

8. Cheri Mossburg, et al. “A 75-Year-Old Asian Woman Says She Fought Back after Being Attacked in San Francisco,” CNN, 18 Mar. 2021.

9. Maria Medina, “Public Defender: Attack on Elderly Asian Woman in San Francisco Not Racially Motivated,” CBS San Francisco, 8 Apr. 2021.

10. “About,” Stop AAPI Hate.

11. Ibid.

12. Leonardo Castañeda, “For Those Tracking Anti-Asian American Hate, the Work Brings Trauma and Healing in Community,” The Mercury News, 19 June 2021.

*This is one of the projects completed by The Nikkei Community Internship (NCI) Program intern each summer, which the Japanese American Bar Association and the Japanese American National Museum have co-hosted.

© 2021 Laura Kato